IT WAS once generally believed that in the unlikely event of the whole of the world being destroyed with the exception of the British Museum, what we fondly call ‘civilisation’ could restart with the knowledge contained in that building in WC1B 3DG.

Whether that is still true, what with the advances in IT, AI and the digitisation of vast archives into cloud servers scattered across anonymous data centres, is up for debate.

But there remains something stubbornly essential - perhaps even reassuring - about a place where human curiosity, creativity, controversy and folly are preserved in physical form.

History almost literally spills out of the cabinets and cupboards, the display galleries and shelves of this imperial-looking colonnaded building.

This is without doubt one world’s greatest treasure troves, but the British Museum has never been short of controversy.

You don’t get to be the most visited tourist attraction in the UK without a few skeletons in the storage vaults, both physical and metaphorical.

The Sir Hans Sloane statue in Killleagh (geograph.org for Wikimedia Commons)

The Sir Hans Sloane statue in Killleagh (geograph.org for Wikimedia Commons)The museum was founded by a County Down man Hans Sloane (1660–1753) physician, naturalist, and collector whose legacy helped shape some of Britain’s greatest institutions — but at a moral price.

Born in Killyleagh, he studied medicine in Britain and Europe before travelling to Jamaica where he continued his botanical interests.

In a move that was to be crucial to the future of the British Museum, he married the widow of a wealthy Jamaican planter. Sloane was able to indulge his passion for collecting artefacts of all sorts — natural history objects, books, coins, natural curiosities.

This collection was bequeathed to the nation and became the basis for the original British Museum and its offspring, the Natural History Museum.

Though celebrated for his scientific curiosity, Sloane’s legacy is complex.

He was a supporter of colonialism — or the British Empire’s outreach programme as it undoubtedly liked to call itself. We may assume he would be happy that the museum was stuffed with artefacts from the far corners of the world — mostly looted, sometimes borrowed, sometimes traded and occasionally bought.

But there’s no question that the wealth of this County Down man was tied to colonial plantations and slavery, a fact that has prompted re-evaluation of his contributions in recent years.

In 2020 the bust of Sir Hans Sloane was placed in secure storage alongside artefacts explaining his work in the context of the British Empire.

Whatever the controversies today, the British Museum has retained its position as the UK's most visited attraction for the second consecutive year, counting 6.4m visitors last year.

The figures, published by the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions (ALVA), show that the museum saw an 11% growth in annual visitors.

Six of the best — the top Irish must-sees at the museum

The Londesborough Brooch

This stunning 8th or early 9th century silver brooch is a masterpiece of Celtic craftsmanship, created during Ireland’s artistic golden age. Comparable to the famous Tara Brooch and Ardagh Chalice, it showcases the intricate detail and prestige of early Irish metalwork—a powerful symbol of Ireland’s rich cultural legacy.

The Kells Crozier

An ornate staff linked to the Abbey of Kells in County Meath, this ecclesiastical artefact dates between the 9th and 12th centuries. Once a symbol of religious authority, it features a copper-alloy crook later overlaid with silver. Though the exact location of its unearthing remains uncertain, it is a hugely impressive object from Ireland’s past.

The Kells Crozier (Johnbod on WIkimedia)

The Kells Crozier (Johnbod on WIkimedia)The Bell Shrine of St. Conall Cael

This shrine, crafted in the 10th or 11th century, encases a 7th century iron bell said to belong to St. Conall Cael of Inishkeel, County Donegal. The piece combines spiritual reverence with artistic flair, adorned with bronze and intricate detailing—an echo of Ireland’s early Christian heritage.

The Bell Shrine of Conall Cael (image by Ceoil on WIkimedia Commons)

The Bell Shrine of Conall Cael (image by Ceoil on WIkimedia Commons)The Breadalbane Brooch

Blending Irish and Scottish influences, this 8th century silver-gilt brooch is a beautiful cross-cultural artefact. Its elegant D-shaped design features gilded geometric motifs and stylised bird-head terminals, marking it as a high-status object from the Celtic and Pictish traditions.

The Dowris Hoard

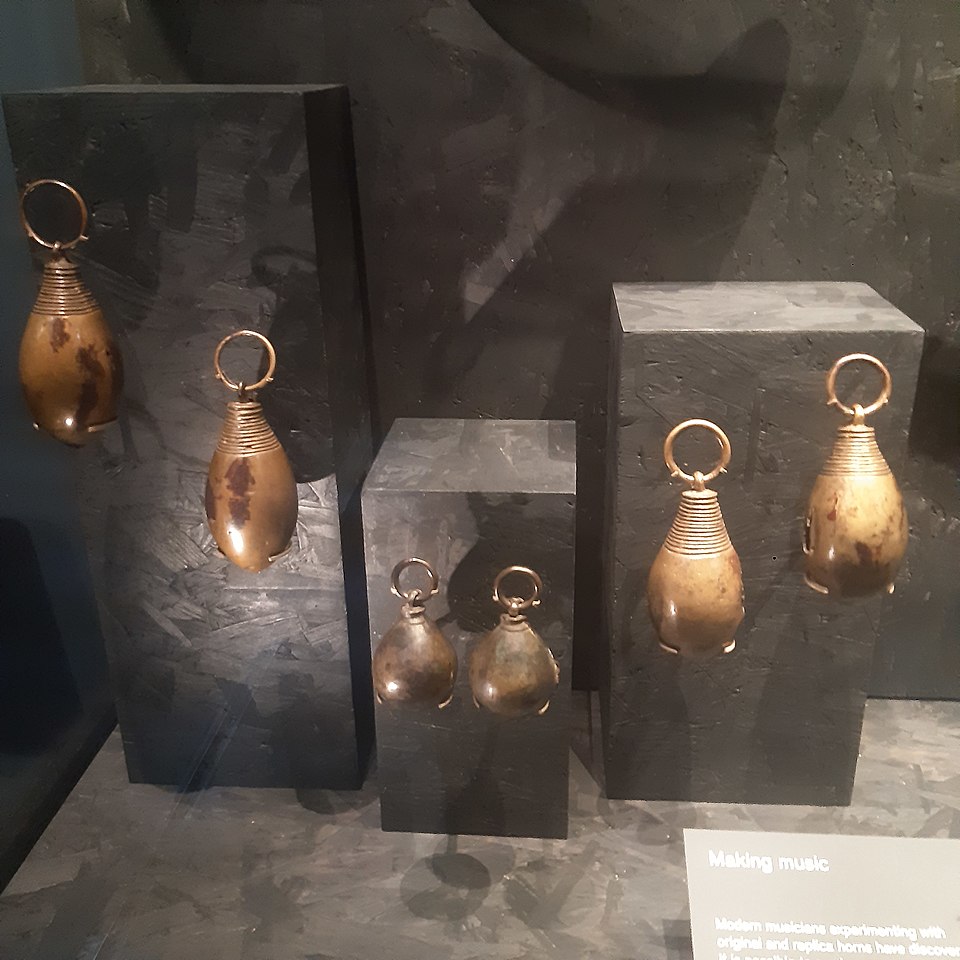

Unearthed in County Offaly, the Dowris Hoard consists of over 200 Late Bronze Age items—tools, weapons, and musical instruments—likely deposited as part of a ritual. Now split between Dublin’s National Museum and the British Museum, it offers a window into prehistoric ceremonial life in Ireland. The instruments include curved musical horns, crotals (a type of small bell), and cylinders which may have been used as rattles. Ethnomusicologists have examined the hoard, no doubt to see if there were any mediaeval ould sessions (SPOILER ALERT: there weren’t)

The Dowris Hoard (Jononmac46on Wikimedia Commons)

The Dowris Hoard (Jononmac46on Wikimedia Commons)The Mooghaun North Hoard

Discovered in County Clare, this extraordinary Bronze Age gold hoard once contained over 150 objects, making it one of Europe’s largest.

The other exhibits

The Lewis Chessmen

In the interests of equality, it should be pointed out that there are Lewis chesswomen in this collection too.

The kings, queens, pawns, knights etc are today split between the British Museum and the National Museum of Scotland. First discovered on the Isle of Lewis in the Hebrides, it's not certain where they were from originally.

Made from walrus ivory and sperm whale tooth, so a viable theory is that they originated in Trondheim in Norway around 1150–1200. This was a centre for that form of mediaeval craft. To bolster that claim, the Chesspeople's thrones resemble carvings in medieval Norwegian churches.

The Rosetta Stone

The crown jewel of the museum’s Egyptian collection, the Rosetta Stone was key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. It's an absolute must-see.

The Sutton Hoo Treasure

This Anglo-Saxon burial hoard is jaw-droppingly beautiful—especially the helmet. It’s like something out of Tolkien, except it’s real, and it's one of the most important archaeological finds in British history.

The Assyrian Lion Hunt Reliefs

These enormous wall carvings from the palace of the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh (modern Iraq) show brutal royal lion hunts in incredible detail. They’re almost 3,000 years old but feel vividly alive. Carved into soft gypsum around 645 BC, the craftsmanship is impressive, the cruelty palpable.

The Egyptian Mummies

The museum's ancient Egyptian mummies are legendary. You can see preserved bodies, sarcophagi, and the rituals of death and the afterlife up close—truly fascinating (and a bit eerie).

Pillaged or preserved?

THE big question lingers over the British Museum: should these objects be here at all?

That debate, roaring most vocally around the Elgin Marbles and Benin Bronzes, doesn’t spare the Irish material.

Some would argue that Irish history belongs in Ireland, especially post-independence.

Others make the case for accessibility and shared heritage.

After all, few places offer such a sweeping sense of interconnected pasts as this echoey leviathan of a building. Truly, there’s no place like the past.

So is the British Museum a comfortable day out?

Perhaps the answer lies in how we choose to see the place.

The British Museum isn’t just a collection of objects; it’s a mirror of historical power. But mirrors can reflect as well as distort.

When those subjected to the full force of the not-so-benigh British Empire, including Irish visitors, walk these halls, they carry with them their own narratives, their own inherited stories.

That brooch, that boat, that stone carving that statuette, that ancient map—they mean something different to us. They always have.

In the end, the British Museum is what you make of it: a vault, a forum, a battleground, a time capsule.

For Irish visitors, it’s all those things and more. It's a chance to trace lines across history's map — even if some of those lines were drawn without our say.

Museum admission is free, although guided tours are available for which you have to pay (typically between £15 - £20)

Multimedia guides, which you download onto your phone, cost £7. Themed and special interest tours are available on selected days — consult the website (prices vary).

For further information click here.