DAYS like this were meant to belong to the past. Money – we were told – decided everything, as those with the deepest pockets bought the best coaches, best players, and therefore, the title. Well, the year of the underdog has changed all that. First Leicester City, now Connacht.

Saturday’s Pro12 final victory in Edinburgh will be remembered forever in the western province, but it will also be stored in the hearts and heads of those of us whose love of sport originated in tales like this, stories that went beyond borders, geographic or otherwise.

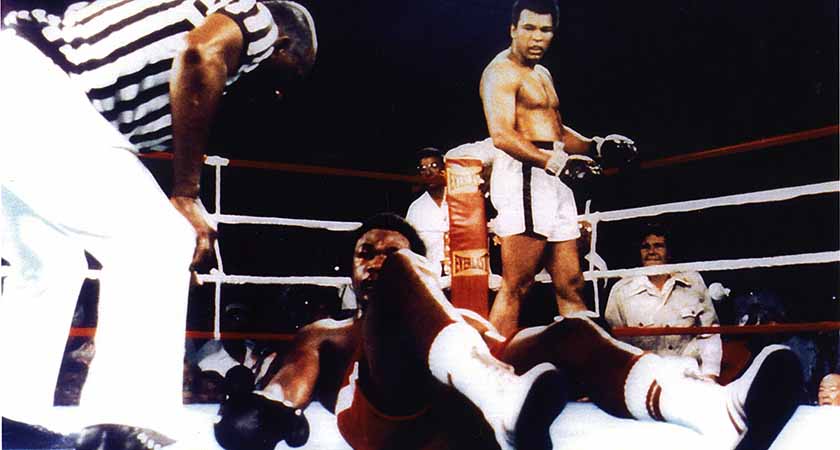

Children of the 70s had no shortage of like-minded fairytales, from Derby County and Nottingham Forest’s improbable English titles – and in Forest’s case – European Cup triumphs, through to that day in 1974 when millions of people across Britain and Ireland set their alarms for the early hours of a Wednesday morning to watch an apparently washed-up Muhammad Ali achieve his improbable victory over George Foreman.

Ali knocked out the ruthless Foreman in Zaire

Ali knocked out the ruthless Foreman in ZaireBy the 1980s, the names changed but the theme remained. Galway and Offaly could emerge from the darkness to dominate large chunks of the hurling decade, Stephen Roche could win the Tour de France, Barry McGuigan could unite a divided society in Northern Ireland and capture a world title, teams like Coventry City, Wimbledon, Oxford United and Luton Town could win England’s major cups over a three-year-period.

Anything seemed possible. And then nothing did. Sky TV was born. Venture capitalists discovered a new business opportunity – it was called sport. And in this new world order, fairytales didn’t matter, money did. Clubs were floated on the stock exchange, stadiums increased in size, as did player salaries, and all of a sudden the days of a Brian Clough being able to mould a team of misfits and rejects into the best in Europe seemed quaintly old-fashioned.

Yet that was football. Other sports differed. Didn’t they? Initially, they possibly did. When rugby turned professional, Brive, a provincial French club from a town with a population of 50,000 people captured the second Heineken Cup, beating Leicester in one of the most thrilling finals there has been.

By the end of the decade, though, they were financially outmuscled and while they are back in the French Top 14 again, it is as makeweights, not as major players.

And their story is the common one. Before Brive, there was Blackburn, winners of the 1995 Premier League. The wealth of a local businessman was enough to finance them a title then, but would not buy them a world class centre forward now.

Connacht captain John Muldoon and head coach Pat Lam pictured as thousands turned out to greet their heros in Galway [Picture: ©INPHO/James Crombie]

Connacht captain John Muldoon and head coach Pat Lam pictured as thousands turned out to greet their heros in Galway [Picture: ©INPHO/James Crombie]That’s just how it is. Money talks, players walk. The Forbes list of the world’s richest football clubs also happen to be the same names as the Champions League winners over the last 20 years, give or take one or two exceptions, namely Porto in 2004 and Ajax in 1995.

In rugby, it’s a similar story. Toulon and Saracens have become the continent’s big spenders and, predictably enough, the continent's most recent champions. English and French TV money dwarfs the income coming into the Pro12, hence the presence of eight French and English teams in this year’s Champions Cup quarter-finals.

So in this context, last Saturday was a special day – for Connacht, certainly, but for sport, too. Budget-wise, they started the season as the ninth, possibly tenth, best financed side in the Pro12 and their playing squad contained fewer internationals than everyone else.

Add in the weight of history, too. Never before, in either the amateur or professional era, had they reached a final, never mind win one. Plus, there was the whole 2002-03 saga, when the IRFU considered shutting them down. As they fought for survival then, they also appreciated that if they were to turn their fortunes around, a coherent plan was needed.

Underage structures were reformed and uncut gems were recruited. Bundee Aki and Niyi Adeolokun have added class to the backline, while the additions of Finlay Bealham, Ultan Dillane and Matt Healy – who’d slipped through the net at Ulster, Munster and Leinster respectively, served as a reminder of Connacht’s value and also of how short-sighted the IRFU were 14 years ago.

Ronan Loughney with the trophy at the homecoming in Eyre Square [Picture: ©INPHO/James Crombie]

Ronan Loughney with the trophy at the homecoming in Eyre Square [Picture: ©INPHO/James Crombie]As it is, they’re here, champions of the Pro12, and champions of a cause: sport’s cause, a reminder that the unexpected can happen and that men like John Muldoon, who spent his entire career with his home province, can get to savour days like these. “Sport can be cruel sometimes,” the 33-year-old said after Saturday.

“I’ve walked off the pitch a couple of times and said, ‘Right, that’s me done, I’m not staying here’.

Unfortunately, at times I felt we weren’t moving as quickly as I wanted us to, felt that I needed a place to transfer to another club, but Connacht is where you are from and it is what you are. You always believe success will come, but when you’re going through tough days it’s always harder to believe.”

On Saturday, his persecution ended.