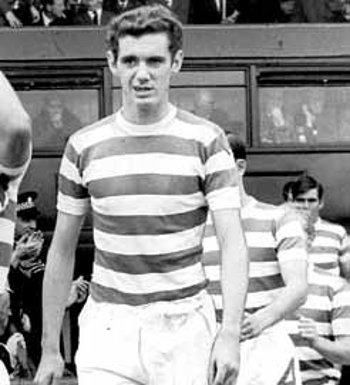

AMONG a distinguished generation of Celtic supporter there is one name that unceasingly taps into a wellspring of imagined possibilities, mythological ‘last orders’ pub stories and a talent in a league of his own. His name is George Connelly.

Last Thursday John Paul Dykes launched The Quality Street Gang at Celtic Park. Dyke’s story focuses on Glasgow’s street-fighting years, during the late ’60s and early 1970s when Jock Stein produced Scotland’s most talented and hard-working reserve side.

But what about the great hopes you knew nothing about? Tony McBride is one of those, he turned up at Celtic Park last week, after overcoming some difficult times.

As a budding youth player he won comparisons to one of Celtic’s greatest in Jimmy Johnstone from both Jock Stein and Sean Fallon, the late Sligonian in his famous Irish brogue called him a ‘pocket edition’ of Jinky.

But McBride was attracted to nefarious street life like a moth to flame. Despite the best efforts of Stein and Fallon, McBride traded first team stats for a criminal record.

Another player who struggled with discipline was Jimmy Quinn, the grandson of the legendary player of the same name also ended up on the wrong side of the law.

Sean Fallon’s emotive voice is an essential part of the narrative spine — he was given the dirty job of telling a player they wouldn’t make it and it broke his heart, to the point he would lie awake at night because he knew these young men came from tough inner-city backgrounds, from Scotland’s industrial and shipbuilding heartlands. They would never get over not playing for Celtic, adding to a long list of dysfunction and loss.

But many of those boys from sodium-lit council schemes ignited Celtic Park with an unforgettable fire.

Arguably Quality Street produced the most complete player the British game has seen in Kenny Dalglish and one of Celtic’s most-loved greats, Danny McGrain.

David Hay and Lou Macari also come from this prodigious group of players. But arguably the biggest talent of all was ‘Geordie’.

One persistent question asks why George Connelly wasn’t playing against Feyenoord in the European Cup final on May 6, 1970.

He had given the performance of his career in the semi-final scoring against Don Revie’s Leeds (Celtic won 1-0) but wasn’t picked for the 1970 final.

In 1973 amid stiff competition he won Scottish Player of the Year. Yet it was from here that Connelly entered the proverbial downward spiral.

This is the player Jock Stein had publically earmarked to replace Lisbon Lion captain Billy McNeill.

Stein stated he wanted to build a team round this versatile ‘modernistic’ talent who while often playing left-half and inside-forward could play anywhere.

He had also won worthy comparisons to Franz Beckenbaur. Jock Stein and Sean Fallon fought hard to save Connelly’s career but with “an appetite for self-destruction” he achieved his dream of near obscurity.

It’s been a hard fact for those who witnessed Connelly to swallow the bitter pill of him walking out on Celtic.

In the digital age everything is over-analysed, debated and repeated until the mystery is gone. The ambiguity as to why Connelly left Celtic continues.

He is often described as a “country bumpkin” from the Fife mining town of High Valleyfield.

He traded his village for the bright lights of Glasgow and a tough working-class dressing room where the banter was thrown thick and fast. It was a challenge. Words often associated with him are ‘shy’, ‘sensitive’ and ‘introverted’.

He was something of an outsider, his tall physical appearance, east coast accent and sense of being different marked him out for some ribbing and practical jokes that perhaps went too far.

There have also been stories of mental illness and alcoholism.

Rumours in Glasgow have always abounded that a teammate had an affair with Connelly’s then wife — it was known to be a difficult and troubled marriage.

The rumours reached such a level that Connelly’s former teammate John ‘Dixie’ Deans decided to address them in his 2011 autobiography in which he denied any involvement. He does allude to one training ground punch-up between himself and Connelly but the Fifer’s account isn’t given.

In truth Dixie Deans’ style is brash and clunky, he comes across more of a pub bore than anything else, offering a glut of platitudes and little of worth.

As Dykes points out he was a ‘controversial’ signing, bringing values into the player culture at Celtic not appreciated by Jock Stein.

Connelly had friends and protectors who looked after him in the dressing room, David Hay and David Cattanach in particular. Once they left the club, the player was left vulnerable. George Connelly appeared at Celtic Park in 2006 and released a book in 2007 but has subsequently disappeared from view once again.

Paul John Dykes’ release will undoubtedly bring him back into the zeitgeist and is a welcome addition to the Celtic canon of literature, offering a valuable and fresh perspective on one of the most discussed and celebrated stages in Celtic’s illustrious history.

At his book launch, someone was overhead to ask: “Do you think George Connelly will appear tonight?”

We were all wondering.