THE remembrance day poppy has recently been a contentious issue for a number of Celtic fans.

The “No Bloodstained Poppy On Our Hoops” protest organised by the Green Brigade proved to be a divisive one among Celtic supporters back in November 2010.

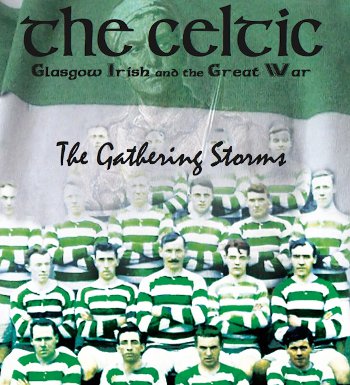

The marking of the 100-year anniversary of the Great War have already sparked varied debate among politicians and the media in Scotland; the release of a new book The Celtic, Glasgow Irish and The Great War: Gathering Storms by Ian McCallum, a former soldier (among many other occupations), is likely to stimulate even more deliberation.

It’s the first release in a new six-part series which examines the social history, political atmosphere and wartime experiences of Glasgow’s Irish Catholic community. McCallum offers a balanced study of the community’s support for the British war effort as well as its relationship with Irish Home Rule.

Gathering Storms offers a fascinating account of the men who built Celtic, giving us a sense of the events and dynamics that created the club. The most striking figure remains the original Mr Celtic: William Patrick Maley.

Signing for the team as a player in 1888 and becoming the club’s first manager in 1897, the Newry-born man fashioned Celtic to become the most successful, robust and wealthiest club in Britain.

In 1897 rivalry with Rangers wasn’t on his radar; aside from being a club of sporting excellence the manger/club secretary dedicated his life towards creating an eminence that would make Celtic a known and respected club throughout Europe.

From the team’s philosophy of attack to how they were perceived outside the community, Maley stage-managed every aspect of the club, dedicating his life to the institution over a period of 43 years and guiding them to 30 major trophies.

Ian McCallum deconstructs Maley’s life focusing on the significant relationship with his father, the British army sergeant Thomas Maley, which provides a vital clue into why Celtic were different from other Irish clubs such as Edinburgh’s Hibernian.

Celtic fans show their support for the club

Celtic fans show their support for the clubHe persuaded Willie’s brother Tom to quit playing for Hibs as he felt the club were not inclusive and stunted the integration of Irish Catholics into Scotland.

It was also Tom who Brother Walfrid had selected to manage Celtic, but on a casual visit to the family’s Cathcart home, Willie accepted the invitation. But only after Maley senior gave the Marist’s vision his seal of approval.

McCallum rightly suggests the fate of Celtic would have been very different without Maley; he summons the range of influences that shaped him, in turn fashioning Celtic: “In the military’s male-orientated world, the ethics of duty, self-discipline, hard work, respectability and self-improvement were instilled into the Maley boys and would remain with them throughout their lives.

Despite the family’s obvious Irishness and their undoubted prolonged and active support for constitutional Irish Nationalism — all four brothers were known to have spoken on Nationalist platforms — the sons of old Sergeant Maley most certainly felt they owed a large degree of loyalty to the land that had adopted them.”

Willie Maley certainly grafted his personality and character onto Celtic. Another story tells of the Irish manager overseeing the design of Celtic’s 1893/94 Scottish League Championship flag, when the silk emerald material was embossed with a Union Jack in the top left quarter.

Undoubtedly such a sight on any piece of Celtic memorabilia would be frowned upon today but the story offers us a significant degree of perspective.

Ian McCallum's new book

Ian McCallum's new bookMcCallum’s evidence goes further revealing that designs with Scottish and British symbols associated with the club were more apparent than perhaps thought.

Links between the Celtic board or staff and the British military were also part of the club’s fabric. Soldiers were as visible as priests among the ranks of the support as both were allowed free entry into Celtic Park, and many former players had been soldiers themselves — British Army bands even provided the pre-match entertainment.

Celtic organised matches against military teams and even secured the services of a few players when doing so. Celtic even had their own cricket team.

Joining the army for many working class Glaswegians of Irish or Highland stock was something of an economic necessity, it also offered an opportunity and a sense of adventure.

While many of the Glasgow Irish would have been supporters for Irish Nationalism the need for economic stability and an escape from the slums outweighed political affiliations.

During that process many retained something of their identity by supporting Celtic — the club like them was made up of both Irish and Scottish influence.

But joining a British regiment was equally an equally absorbing shift with new loyalties, comrades, traditions and badges of identity. As McCallum points out the Highland Light Infantry was considered Glasgow’s own regiment.

The Gathering Storms is a demystifying and captivating read that will challenge many supporters on what they perceive the club to be.

While it’s widely accepted that Celtic are both Irish and Scottish they were shaped by a very British Celt in Willie Maley — a devout Catholic and ardent royalist, an Irish nationalist, imperialist, socialist and supporter of the British army and establishment.

Undoubtedly it’s these varied loyalties that make Maley such an intriguing figure. He remains a vital cornerstone of the club today and he anchored Celtic during a period of economic instability, world war and social turmoil.

In modern times Celtic have underlined the importance of Maley’s ethos.

A few seasons ago they stitched the inside collar of the club jersey with one of his most famous quotes, it said: “It’s not the creed nor his nationality that counts. It’s the man himself.”

For more information on The Celtic, Glasgow Irish The Great War: The Gathering Storms visit www.theglasgowirish.com