It’s almost 21 years since Alan McLoughlin hit a stunning late equaliser against Northern Ireland on a never to be forgotten night in Windsor Park.

In an extract from his new book A Different Shade of Green, with Bryce Evans, the Manchester-born Irishman offers a compelling insight into the spectre of sectarianism that struck fear into Jack Charlton’s squad ahead of the qualifier and the goal that sent Ireland to the World Cup in USA 1994.

One Night in November, 1993

I WAS sitting on the Republic of Ireland team coach as it wound its way through Belfast when the fear hit me. Similarly, it was completely silent and it was dark, about 7pm in the evening. The bus snaked past mean, red-bricked streets. Dank, claustrophobic housing. Tribal colours fluttering menacingly, illuminated by streetlight. Hostility.

Under Jack Charlton’s management, the Irish team coach was not usually quiet; there’d be some come-all-ye folk ballad blaring and plenty of craic between the players. But on this occasion, uniquely, the reason for having the lights and sound off was security.

We were travelling to play Northern Ireland in our final qualifying match in the World Cup campaign, a make-or-break game which would decide whether or not we would be travelling to America the following summer to compete in the World Cup finals.

We knew that we had to win to ensure qualification. If Spain beat European champions Denmark in Seville, a draw would be enough for us to get through. Northern Ireland had failed to qualify. One thing was certain, though: they could still stop us from going through that very evening if they managed to beat us.

With such high stakes, not to mention the hand of Irish history, the atmosphere was sure to be charged. But there was an extra edge. The match was taking place after a spate of killings. Three weeks previously, two IRA men had entered a fish and chip shop on Belfast’s Shankill Road, intending to leave a bomb for a group of loyalist paramilitaries meeting upstairs. It exploded prematurely, blowing the bomber and nine other people in the chip shop to smithereens.

Loyalist paramilitaries responded a week later, carrying out a wanton shooting at a pub in County Derry, killing eight. I remembered the news bulletin, which claimed that one of the gunmen had shouted ‘trick of treat?’ as he opened fire.

Although I was playing my club football in England, the horror of the Troubles was only ever a newsreel away. Tit for tat. 9-8? The grim tallies of the dead in both atrocities were close enough to seem like some sort of grotesque football score. The footballing authorities, understandably, were starting to become unnerved. There was talk of postponing the match, or playing it elsewhere — in Wembley or even in Rome.

Then it was decided that the match would go ahead, as scheduled, at Windsor Park, Belfast. For security reasons we were instructed to fly the short distance back from Belfast to Dublin, which did little for everyone’s nerves. We were all very brazen about actually playing the match; everyone had the attitude of ‘let’s just do it’, and yet at the back of all our minds was creeping worry. Would athletes be targeted? Ha, ha! No way. Surely not! Shrug off the fear lads, and move on.

However, in the days before the game someone mentioned the 1972 Olympics when members of the Israeli Olympic team had been gunned down by the Palestinian group Black September. There was that momentary, stomach-tightening fear again.

So, as the coach passed through the tight Belfast streets, past the red, white and blue kerb-stones and triumphant murals of King Billy on his horse, minds raced with anxiety. Sitting in darkness, everyone was silent. I looked up and down the coach to the two special branch men, disguised in Football Association of Ireland tracksuits to blend in with us players. Even they seemed to be stroking their guns nervously.

As the coach drew up outside Windsor Park stadium, the escort of armoured cars started to pull away. I looked out of the window, first to the police helicopter still whirring noisily overhead and then to a set of five-a-side pitches illuminated by floodlights. I thought it was odd that they were empty; there should have been kids enjoying a kick-about. And then I saw the kids. Dozens of them, of all ages, from about 10 to 18. They had spotted the coach and were converging on it.

Undeterred by the police dogs bordering the stadium, this young mob crowded around the coach, making gun signs with their hands. Every single one of them. With two fingers outstretched and their thumbs cocked, dozens of fingers rapped menacingly on the coach windows. “Fenian bastards!” Their lips pouted into a ‘bang’ as if they were pulling the trigger and blowing us away.

THE fear that night in Belfast was more manageable because I was part of a band of brothers. Sure, the dark, silent final moments of that coach ride into the city were unnerving. But we dealt with the fear, as lads do, by cracking jokes. The hotel where we were staying before the game was out in the countryside, surrounded by a big golf course.

Everywhere you looked, across the stunning grounds, there were Alsatians and policemen. Armoured cars patrolled up and down the drive and, of course, we had our armed plain clothes men in tracksuits masquerading as players. First we joked about whether Jack Charlton would, in his blustering and occasionally blundering way, accidentally put one of the special branch fellas in the starting line-up.

Then, with black humour, we started speculating about who would be assassinated first. We all agreed that it would be the boss, Big Jack, and pretended to be relieved at this fact. Why Jack? Well, he was an easy target: a mountain of a man with ruddy cheeks, flat cap, a booming Geordie accent, and a purposeful stride. More importantly, though, he had a distinctively long neck. So long, in fact, that the players nicknamed him ‘Swanny’. ‘Don’t worry, we joked, if anyone’s going to take a bullet it’ll be old swan neck.’

What’s more, the security concerns weren’t going to put Jack off his pre-match ritual of leading the squad on a morning stroll. On the morning of the game, Jack and his assistant Maurice Setters were advised by the cops that walking the entire Republic of Ireland squad, all uniformed in tracksuits, around the leafy surrounds of the hotel was not a very good idea.

But Jack would have none of it. So off we all set, behind Jack, accompanied by several policemen with semi-automatic weapons and an armoured car that trundled across the golf course tearing up the beautifully landscaped fairways with its dirty great tyre tracks. I can only imagine the groundsman’s face when he saw the state of the 18th later that day.

SITTING on the substitutes’ bench I heard every single word because there was no Perspex glass behind us in the Windsor Park dug-out. I had never heard so many different expletives, and all accompanied by the words ‘Taig’ or ‘Fenian’. There were threats on my life, my kids’ lives, slurs about my mother, you name it. I just made sure not to turn round and make eye contact.

Police forces on both sides of the border had urged fans to stay away but there were a few Republic of Ireland fans among the 10 thousand or so spectators in that intense little ground. Those that were there must have been sitting on their hands. And who could blame them? If you’re a Catholic, they say, Windsor Park can be about as welcoming as the ninth circle of hell. Jack Charlton claimed he had never seen a more hostile atmosphere in all his playing or managing days ‘not even in Turkey’.

The atmosphere was not helped by Billy Bingham, the Northern Ireland manager, who had criticised what he called the Republic of Ireland’s ‘mercenaries’. He was referring to English-born players like me whom, he claimed, had chosen Ireland because ‘they couldn’t find a way of making it with England or Scotland’. That wound me up. Promising to reporters pre-match that the North would ‘stuff us’ Bingham made his way around the pitch before the kick-off, waving his arms to the fans, getting them stoked up.

Oddly though, by contrast to the ‘mercenaries’ slur, I regarded this act as mere gamesmanship; irresponsible perhaps, but more about pride, more of a football rivalry thing than a sectarian thing. Maybe I was just trying to impose the normalcy of competitive sport on a very abnormal situation by playing tricks on myself, trying to keep calm. Meanwhile, back on the bench, I was busy winding up our reserve goalie, and my close friend, Alan Kelly.

‘Oh my God!’

‘What is it, Macca?’

‘What’s that?’

‘What’s what?’

‘That little red spot on your forehead. I’m serious’

‘What?’

‘I think ... is it? ... Oh God, a red spot ... it’s ... a sniper must have you in his sights!’

The dark humour was just our silly way of hiding the anxiety. Windsor Park that evening was a very strange place to be and the safest place was definitely on the pitch. For the rest of the match I shut out the abuse by engrossing myself in the game. Slowly, news started trickling through from Seville ... the Spanish goalie Zubizarreta had been sent off after only 10 minutes. Surely, Spain couldn’t hold on against the Danes with only 10 men?

But hold on the Spanish did and, better still, went 1-0 up after an hour. If Spain could protect their lead, a draw would be enough for us. With things going well in Seville, Jack decided we should push for the winner. On 70 minutes, and with the game still at 0-0, Jack signalled to Ray Houghton to come off and told me to get on the pitch, to pick up loose balls behind our front two men, and to do my damnedest to get us the winner.

As I rose from the bench I could sense dozens of people in the stands behind me getting up too, with the sole intention of being able to hurl expletives at me more volubly. ‘Keep calm, keep focused’ I told myself. I removed my tracksuit, and busily tucked my shirt into my shorts. With the crowd spitting hatred at me, I stood on the touchline poised to enter the fray. ‘Come on ref!’ It seemed like an age before he stopped play and Ray trotted over. It was a blessed relief to leave that substitutes’ bench and get on the pitch.

JUST after I came on that night in Belfast, Jimmy Quinn put Northern Ireland 1-0 ahead. It was a wonderful goal, a rifled volley. Packie Bonner had no chance of keeping it out. I knew Jimmy. When I’d signed for Swindon Town seven years previously (as a snot-nosed nineteen-year-old) Jimmy, an older pro, had taken me under his wing, regularly inviting me over for Sunday dinner with his family.

But with that goal, my heart sunk. Defeat would put us out. I’d settled down to roast beef, gravy and spuds with that man. Now, as his teammates crowded around him in celebration, it looked like our American dream was over, killed by the avuncular Jimmy.

I looked back over to the bench, where Jack Charlton appeared as if he was about to explode, kicking every ball, mouthing swear words, and flapping his arms around. Because I was on the pitch I was not aware until later of the famous altercation that had occurred after their goal. When Jimmy Quinn scored, Northern Ireland assistant manager Jimmy Nicholl had made sure to rub it in, shouting ‘up yours!’ to Maurice Setters.

Shortly thereafter, as has gone down in the lore of that evening, Jack Charlton turned to Tony Cascarino and told him he was coming on. But Cass, being Cass, had left his jersey in the changing room. As he hurriedly unzipped his tracksuit, he was confronted by just a white cotton T-shirt.

When Jack asked him what was taking him so long, Cass confessed his mistake and naively offered to play in his T-shirt instead of an official jersey. Jack was so angry I think he almost murdered him there and then. If something didn’t change, and quick, our World Cup adventure would be over.

Then, minutes later, up the other end, we won a free kick for what looked to me like a fairly innocuous shoulder barge. Denis Irwin stood statuesque in the wind, ready to swing in one of his trademark free kicks with his right foot. I hovered on the edge of the box. Denis looped it quite deep into their box.

As the ball was headed clear by a defender, I was there, loitering. I sensed Niall Quinn to my left, using his ample frame to obstruct Iain Dowie and allow me space for a shot. Grateful to Quinny, I concentrated hard on the ball, thinking to myself that I needed to chest it down rather than snatch at it. In that killer moment, calm came over me. Momentarily, all the noise in the stadium disappeared. As the ball came to me, in my head I was back at Manchester United, the club that had signed me up as a 16-year-old. I was in the indoor gym with the shale pitch, the same pitch where my Dad’s hero Georgie Best had trained, and where I had stayed on religiously after training every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon by myself, practising volleying the ball against the multi-coloured spots on the wall, painted on for target practice.

I pictured the little red spot on the bottom left of the wall in United’s indoor gym. ‘Red spot, bottom left’ I told myself. And with that target, that red spot, in my head, I let fly. Sailing through a swarm of defenders, the shot swerved past Tommy Wright and into the bottom corner of the net. The Northern Ireland players, clad in dark green, seemed to collectively slouch as my smiling team mates in white and emerald sprinted to congratulate me. I wheeled away, fists pumping. It was the goal that would take Ireland to America.”

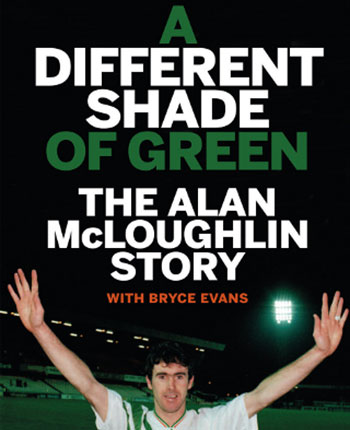

A Different Shade Of Green, The Alan McLoughlin Story with Bryce Evans is now on general release and available to buy on Amazon

(ISBN — 9780992673253: Price £11.99 (st)/€14.99)