AS BEDLAM raged around him, Martin Earley got down from his saddle and held onto his bike, lost in a private world of pain.

This was why he’d left home as a 20-year-old, an innocent abroad, chasing a dream and – far too often – faster cyclists.

He knew he had speed but also limitations. Others were stronger. Others doped. He just got on with life, rode his bike every day, covered miles of road year after year, keeping track with the peleton and this day – May 25, 1986 – getting one over them.

He’s in the autumn of his life now – content with the hand fate dealt him – married and living in Staffordshire to the girl he met at the Los Angeles Olympics, earning a corn as a sports therapist, happy to discuss the Giro d’Italias of 1986 and 2014.

First 1986 and Stage 14 of that year’s Giro, a mountain-top finish at Sauze d’Oulx. He was a young man then, just 23, and had gone from holding a fascination with his bike to being in a position where his talent could carry him up and down mountains at a ferocious pace.

And while he had no reputation as a climber, here – unexpectedly – he was wilfully rejecting form and logic to escape from the pack and go alone for glory.

He got it – one of only two Irishmen to win a Stage in cycling’s second biggest race – and all around him strangers lost the run of themselves, backslappers and hangers-on, wide-eyed fans with emotive faces, sharing in the moment.

And it was momentary.

'Most of my time as a professional was about suffering'

'Most of my time as a professional was about suffering'“For an hour there was elation,” Earley says now. “Then I was back to the team hotel, getting my legs rubbed and ready for dinner. The next day I was back on the bike and racing over another 260km and for an hour and a half, I was in the gutter.

“That’s cycling. Most of my time as a professional was all about sacrifice and suffering. Days like that one in Italy and my Stage win at Pau in the 1989 Tour [de France] made it worthwhile. But it was a hard slog.”

Next week, Irish people can watch 150 of the world’s best riders go through that slog on the roads around Belfast and Dublin, a triumph of organisation and planning that takes Earley’s breath away.

“It is absolutely incredible to know a race of that magnitude – I mean we’re talking about one of the biggest sporting events anywhere in the world – can come to Ireland.

“It’s something I never considered possible. Then again, the Tour de France came here in 1998. It’s an extraordinary achievement for Ireland to host it.”

Yet when Earley was in his prime, extraordinary achievements happened in Irish cycling year after year – Sean Kelly and Stephen Roche producing most of them, as a country with little or no reputation in the sport suddenly had two of the world’s finest riders.

Earley, in contrast, was known as The Third Man, a domestique who acted as the ultimate team player, denying himself for others.

And it was a job he did well, lasting 11 years as a professional, during which time he made a living and a name for himself.

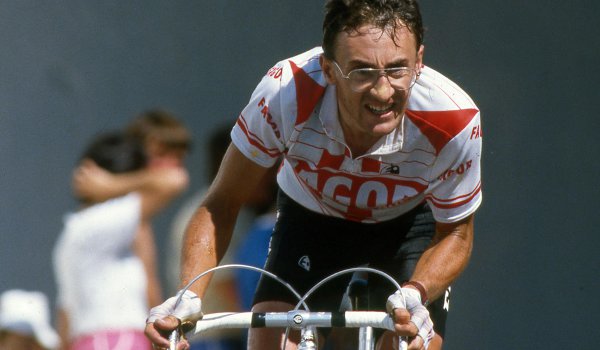

Martin Earley (left) and Sean Kelly (being interviewed) during the Tour de France in 1989

Martin Earley (left) and Sean Kelly (being interviewed) during the Tour de France in 1989“I can’t say it was a normal life because it wasn’t,” he says.

“I mean, you were constantly on the go. Two weeks would never pass without the suitcase being packed or unpacked. Yet it was normal to me because it was all I knew.

“As a young man, heading off to Paris, getting picked up at the airport by the amateur team I was riding for, life was full of hope. It was both a scary and an exciting time.

"You rode for fun and because you had a dream – mine was to become a professional. You entered races and knew if you got a result that the prize money could help make ends meet.

“Then you progressed into the pro ranks. Pretty soon I knew that I wasn’t someone who was hanging out at the back of the bunch. I could hold my own and on my day I could get away and make my mark.

“I had that day in Sauze d’Oulx and again in Pau. That’s something I’m still proud of. It is in my past and I’ve moved on. You have to. But I can look back fondly at that time and feel privileged to have been there when Irish cycling – a minority sport then – went through a boom.

“Sean and Stephen were such great champions. They had that champion’s heart that people speak about. Sean was more consistent than Stephen but they both possessed this incredible ability and when Stephen had a good day, nobody in the world could beat him.”

Years later nobody in the world could beat Lance Armstrong, either. But what we suspected then – and know now – was that Armstrong cheated his way to success.

“What went on was not good for the sport at all,” says Earley. “It has gone through bad times and you hope things are better. They certainly appear to be.

“The one thing I’ll say about cycling is that it is very proactive. This is why the issues come up so often because they chase the cheats and catch them. In other sports, drugs are never mentioned but you’d be naïve to think drug-taking does not go on.”

Innocence carried Earley through the first years of his career but by the time he approached his 30s and had children, he began to consider the sporting afterlife. The road may have been his workplace and the bike the tool of his trade but he knew time was catching up on him.

“The pain was getting worse and there was less and less fun around. One of the other reasons I stopped was because I wanted to be at home. I didn’t want to keep travelling around and being away from my family.”

So he did stop. Well kind of. Mountain biking became his new hobby – one he mastered to the extent that he got to represent Ireland at the 1996 Olympics and in the meantime he completed his studies to enable him to work as a sports therapist.

The peleton moved on and so did he. “Some stay in cycling, some forget about it. I’m kind of in the latter category. I still ride my bike and get the same enjoyment I did as a 12-year-old. I don’t feel the need to go fast anymore.

"I can ride as slowly as any man in the world. I just do it for fun. The competitive edge has been sated. I had my career, and am happy with it.”

Martin Earley will ride the Tour of Kildare this year on August 10. The one-day event supports the Marie Keating foundation. Anyone interested in participating can log onto www.naascyclingclub.com