ONCE upon a time there was this thing called the FA Cup which had a deep resonance with Irish football — particularly whenever Arsenal were involved in it.

Managed by an Ulsterman — Terry Neill — the Gunners captured the 1979 Cup backboned by players from either side of the border: Liam Brady, Frank Stapleton and David O’Leary holding the key Cabinet positions in Neill’s premiership, Sammy Nelson, Pat Jennings and Pat Rice offering significant support from the backbenches.

A year later, a Dubliner — John Devine — took Nelson’s place, forcing the left-back to be content with a place on the bench and bringing the Irish presence at Arsenal to seven for their Cup final appearance against West Ham, the most any one club has ever had.

Fast forward to 2014 and Arsenal are in another FA Cup final, their first in nine years and the first time in 62 years they have reached this stage without any Irish presence either on the pitch or the managerial staff — a symptom not just of the changing face of the club but also the declining status of Irish football.

Once, ours was a significant presence in dressing rooms at Anfield, Old Trafford and Highbury. Yet that is now a distant memory.

With Arsenal, there is a particular poignancy by the ending of an era. Quite apart from the dominant make-up of the team during Neill’s tenure, there was also the mark O’Leary left at the club, playing the last of his 772 games for Arsenal in the 1993 FA Cup final replay victory over Sheffield Wednesday, which doubles up as the last time an Irishman played for the Gunners in English football’s showpiece.

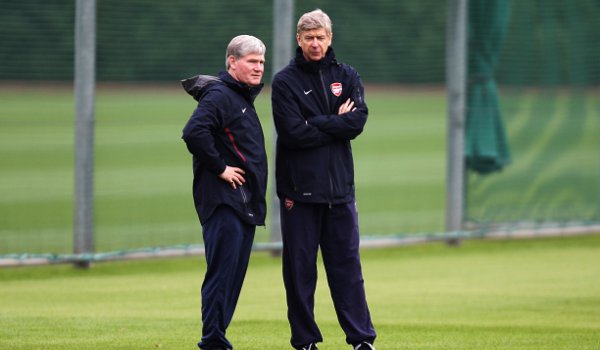

Pat Rice (left) was Arsene Wenger's right hand man, but he recently ended his time at the club

Pat Rice (left) was Arsene Wenger's right hand man, but he recently ended his time at the clubSince then, Rice — captain of the 1979 side and a presence in the 1971, 1972, 1978 and 1980 finals as a player — and then the 1998, 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2005 deciders as Arsene Wenger’s right-hand-man — has also ended his 40-year employment with the club. And joining him on the retiree list is Brady, who for the last 17 years, worked as the head of Arsenal’s youth academy.

“What I want,” Brady said after landing the job in 1997, “is for fifty per-cent of the Arsenal team to be home-grown, capable of winning trophies and in three-years-time for some of our players to be coming from our youth development policy into the first team.

“There hasn’t been an Irish lad emerge from the youths into the first team since Niall Quinn broke through and I want to rectify that.”

His wish was never granted, though. Despite headhunting quality Irish teenagers — Graham Barrett, Stephen Bradley, Keith Fahey and Anthony Stokes were among the most sought-after kids of their generation — Arsenal, under Arsene Wenger, have not brought one Irish player through their system. Nor, despite showing interest at various times in Richard Dunne and Kevin Doyle, has he bought one.

The upshot is that the special link between club and country has been damaged. The new generations of Irishmen following Arsenal do so because of their status as a leading English club, not because of their tradition of being an Anglo-Irish one.

And of course the other side-effect of the Irish absence from Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City, Manchester United and Liverpool’s line-ups is that the national team is made up of players who, for the most part, are stuck fighting relegation battles.

Yet, despite this evident problem, Martin O’Neill is not so worried. “Things have changed for better as well as for worse,” said the Ireland manager. “I am not frustrated by the fact players are at Stoke, Everton, Hull and Aston Villa. Far from it. It is part of life.

“And the undeniable fact is that the Premier League — with its cosmopolitan nature and influences — prepares players for international football better now than when I was playing. I remember way back — 35 years ago — going to East Germany, to Malmo and not knowing a single player who I was up against.

“And I remember Sammy Nelson telling me about the time Arsenal got a thumping in Europe by Dynamo Kiev and how their players didn’t say a word to each other. And yet they were brilliant. The unknown then created a fear.

“Now we should have less trepidation — firstly because the contrast in style between the Premier League and the international game is nowhere near as significant as it used to be. And secondly, because there is not one country in Europe — or even South America — where you wouldn’t know at least five of their players. The more you know about teams, the less there is to fear.”

Yet the more we know about Arsenal — and the way they prioritise globalism over parochialism — we do fear that days like the 1979 Cup final are gone for ever. English football has changed and Ireland, consequently, is in danger of being left behind.