This Saturday the exodus will begin. From Dublin, Belfast, Cork, Tipperary, Waterford, Sligo, Westmeath, Kildare, Donegal, Louth, the north, the south, the east, the west.

They’ll set their alarms, pack their bags, check their tickets, leave their homes, jump into their taxis, step off their flights and dream. Old Trafford will be their cathedral. The Stretford End their adopted home.

They’ll shout, they’ll cheer, they’ll scream. United is their team.

But Manchester has never — nor ever will be — their home. That instead is in Dublin, Belfast, Cork, Tipperary, Waterford, Sligo, Westmeath, Kildare, Donegal, Louth, the north, south, east and west.

By address, Manchester United are an English team, by greed a worldwide brand, but by history, an Irish institution.

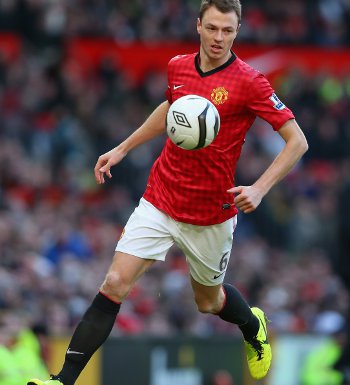

From Johnny Carey to Jackie Blanchflower, Blanchflower to Liam Whelan, Whelan to John Giles, Giles to Noel Cantwell, Cantwell to Tony Dunne, Shay Brennan and Georgie Best, Best to Sammy McIlroy, Paddy Roche and Jimmy Nicholl, Nicholl to Kevin Moran, Paul McGrath and Norman Whiteside, Whiteside to Mal Donaghy, Donaghy to Denis Irwin and Roy Keane and John O’Shea, O’Shea to Jonny Evans, there has been an unbroken chain of Irish players at Old Trafford since 1935.

Soon the flame may flicker out, though. After Evans, who is there coming through? Soon, the only thing Irish about United may be their supporters.

You wonder about the impact.

You wonder if United would be as popular in Ireland if it wasn’t for Carey, Whelan, Best, McGrath, Keane and the dynasty they created. But you don’t wonder for long.

“I’ve lived either in Dublin or Manchester for most of my life,” says Kevin Moran. “The connection is deeply felt. After Munich…”

The words drop off.

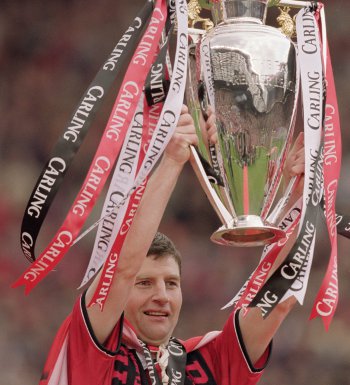

Denis Irwin

Denis IrwinUntil Munich, Manchester United were only beginning to infiltrate the Irish conscience. In the earlier decades of the 20th century, they weren’t any bigger or better than Sunderland or Arsenal or — believe it or not — Huddersfield Town.

They were a club on their knees after the Second World War but were carefully reconstructed by Matt Busby, captained by Carey to a League and FA Cup, but even then were still just one of those clubs in one of those cities.

And then, Manchester United became the Busby Babes and the Busby Babes became the youngest, most exciting English champions of all time.

And then they entered the European Cup. And then they came to Dalymount Park to play Shamrock Rovers — the greatest Irish club of all time. Never before had an English side played an Irish one in a competitive game. This was new.

“We had seen other teams,” wrote Eamon Dunphy in his seminal book on Busby, A Strange Kind of Glory, “Stan Matthews, Tom Finney, Wilf Mannion and Len Shackleton.

Before television, these men were faces on the little black and white cards we collected from sweet-cigarettes. When they came to Dublin, the photos came alive. Your blood ran cold with a shiver of delight.

The ‘Red Devils’ were different to those who came before them. They lived up to their legend that night. They seemed unearthly, handsome creatures from another planet, more heroic than any movie-star we’d seen or could imagine.”

What made them real, though, was the presence of one of our own, Liam Whelan in their ranks. Whelan was so talented he kept Bobby Charlton out of that United team. From his looks, and his football, he may have appeared to be from another planet but by birth, he was from Cabra.

“How could you support anyone else after being at Dalymount that night?” asks Pete Mahon, who would later earn respect and medals as a player and manager in the League of Ireland.

“I grew up in Finglas. Cabra was on our doorstep. Liam Whelan was a Cabra boy. United were the greatest team Dublin had ever seen. The connection was obvious. But Munich made it deeper.”

Today, we can only imagine what effect Munich had on Manchester and Irish society. For generations who lived through The Troubles, other tragedies seemed greater in their severity.

Yet for the people of the 1950s, Munich and the death of Roger Byrne, David Pegg, Tommy Taylor, Eddie Colman, Mark Jones, Geoff Bent, Duncan Edwards and Cabra’s Liam Whelan, had a seismic effect.

“The outpouring of public emotion in Dublin was similar to what happened in London when Diana Spencer died,” remembers Jimmy Magee, then a young journalist living in the city.

“You had no internet then. No TV. No Sky News. No immediate communication.

“You had newspapers with different editions. There were queues at the newspaper stands waiting for the latest headline. We’d heard about the crash, then that some were dead, then the numbers increased. For a while we were led to believe Liam Whelan was alive. When he died, the whole city was in shock.”

A week later, Whelan’s coffin came home to Dublin and from the airport to the family home, six miles away, people stood on the pavements to pay their respects.

Dunphy, Mahon and Magee were eyewitnesses to history. “Men wore their Sunday best and took off the caps as the coffin passed,” recalls Magee. “Women cried.”

“From that moment on, Manchester United became an Irish team,” says Mahon. “You have to remember, Ireland had very few superstars then. Billy Whelan was a genuine star. And he’d been taken away from us. The sympathy for the team and the Whelan family was massive.”

And with that, an Anglo-Irish love-affair really began.

Mahon spent the 1960s travelling across to the games on Saturdays on cattle-ferries before legging it back in time to play League of Ireland football on a Sunday. That was how deep his passion ran.

That decade and the next, in Drimnagh, on Dublin’s southside, Kevin Moran grew up supporting the club he would later play for. These days, he works as an agent and has seen first-hand the English game change.

“In my era as a player, United selected their players from Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales. Now, they pick them from the four corners of the world. From the moment the Premier League started, the shift has occurred.

"At the start, 90 per cent of the players were from the British Isles. Now it is under 30 per cent. There isn’t just a smaller number of Irish players at United — and other — big Premier League clubs. There are fewer English players too.”

As a result, the best talent we produce — the Robbie Bradys and Darron Gibsons — are finding a wall blocking their path at Old Trafford and are realising their careers are best served elsewhere.

Once, in a different era, a John O’Shea would have stayed at United for life. But when Alex Ferguson reckoned his time was up, he moved on. That’s the nature of the modern game where neither sentiment nor tradition count.

Yet Old Trafford remains a home from home for Irish fans. When Evans goes, that link back to the 1930s and Carey may be broken and a connection lost. But Moran can’t see the fans go anywhere else.

“Support for the club passes through families and through generations,” he says. “It won’t wane.”

That much was clear in Glasnevin Cemetery on a February afternoon in 2008. John Whelan, Liam’s youngest brother, was there, tending to the grave. When he arrived, there were two men — no older than 25 — leaving flowers there.

Each wore a United shirt.

“We’re here to pay our respects,” they told him. Neither would have been born until 35 years after Flight 609 crashed on the snowy, Munich runway.

Yet they knew their history and felt the grief and that day, with John Whelan, they were United.