THIS is a story about Ireland as much as it is about George Best. Like the rest of the country, he had his share of Troubles and his fair share of drink. And like too many other Irish narratives, emigration was part of the tale.

Most of all, though, it is a story of what could-have-been. He was brilliant but not for long enough. He was loved but also indulged. His life seemed perfect but in fact was tragic.

And now, ten years after his death, George Best's name remains synonymous with the country as well as with Manchester United and alcohol. His was a life played out in the public eye, from his christening as El Beatle following his return from Manchester United's 1966 European Cup match in Lisbon, when he stepped off the aeroplane with a Sombrero on top of his head and dreams inside it.

He'd fulfil those dreams – winning a European Cup two years later and proving to be, temporarily, the greatest player on the planet, before, at 27, he was gone from Old Trafford.

But while he was there, he was majestic. A great player? He was the Best.

"George was unique," Alex Ferguson said in an interview with The Observer in 1992. "The greatest talent our football ever produced – easily!

“Here at Old Trafford they reckon Bestie had double-jointed ankles. Seriously, it was a physical thing, an extreme flexibility there. You remember how he could do those 180-degree turns without going through a half-circle, simply by swivelling on his ankles. As well as devastating defenders, that helped him to avoid injuries because he was never really stationary for opponents to hurt him. He was always riding or spinning away from things."By the early 1970s, his life was spinning out of control. Not content with being the best footballer in the world, he was also proving to be the planet's most impressive playboy and drinker. If the sixties saw him come of age, the seventies saw his life come apart. It was Miss World, mischief and misadventure. And by 1974, at 27, his career was as good as over.

"It had nothing to do with women and booze, car crashes or court cases," Best said in an interview with Hugh McIlvanney. "It was purely and simply football. Losing wasn't in my vocabulary. I had been conditioned from boyhood to win, to go out and dominate the opposition.

“When the wonderful players I had been brought up with – Charlton, Law, Crerand, Stiles – went into decline, United made no real attempt to buy the best replacements available. I was left struggling among fellas who should not have been allowed through the door at Old Trafford. I was doing it on my own and I was just a kid. It sickened me to the heart that we ended up being just about the worst team in the First Division and went on to drop into the Second."

Many blamed Best for the decline, an accusation which – 30 years later in an interview with Four Four Two – cut to the bone. "Me?" he questioned. "United went into decline for the simple reason that they didn’t have enough good players, and you can’t blame me for that! I didn’t buy the players! They replaced great players with ordinary ones, while passing up the opportunity to buy some excellent players like Alan Ball and Mike England. I also don’t think they had a good manager in Tommy Docherty. I did all I could but I didn’t have the players around me."

Instead he was surrounded by blackguards and nobodies, by blondes and by booze. Regrets? There are only a few.

"Trust me, it was always good fun," he said. "That was one thing I never had problems with at all. How could I feel empty? I will always be grateful to have experienced the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was such an exciting time. The living was free and easy, and there were none of the diseases there are today. Life was about girls, a few beers, football, good music and being a shag-magnet! It was part of life and I loved every minute of it. I was never disappointed with sex."

Others were disappointed with him, though. Bobby Charlton and John Giles – contemporaries from that era – speak poignantly about his talent and how it could have been showcased for longer periods. Temptation, however, got in the way. "If I had been born ugly,” he once joked, "you would never have heard of Pele."

Instead we heard of him drying out in clinics, of his (patchy) attendance at AA meetings, his operations to cure an alcohol ravaged body, his endless efforts to get dry.

"I'd be sitting in AA meetings longing for them to end, so I could get to a bar," he said in that Observer interview in 1992. "When I was supposed to be swallowing those tablets that make you allergic to alcohol – I was married to Angela, the mother of my son, at the time – I was sometimes hiding them behind my teeth and getting rid of them later. And even when I had the implants, I was saying to myself: when the effect of these pellets wears off, I'll have a good drink. So those therapies didn't have much chance of working."

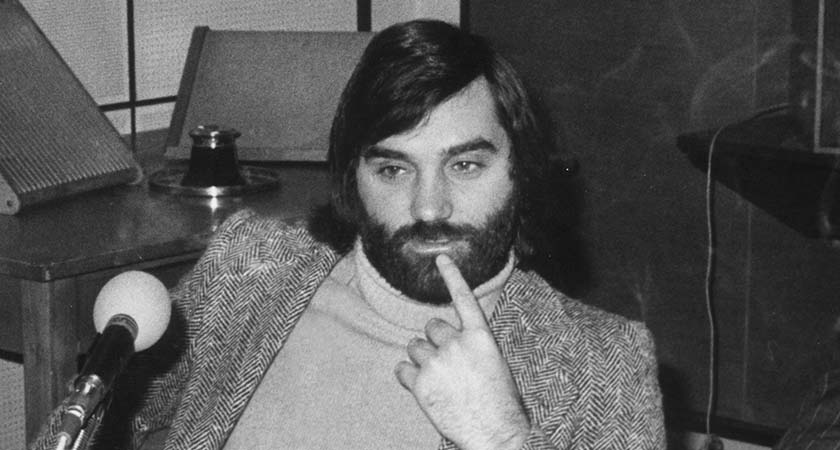

11th March 1975: Best and his biographer Michael Parkinson on Pete Murray's Radio 2 show 'Open House'. (Photo by J. Wilds/Keystone/Getty Images)

11th March 1975: Best and his biographer Michael Parkinson on Pete Murray's Radio 2 show 'Open House'. (Photo by J. Wilds/Keystone/Getty Images)Work, though, kept piling in for George Best. His name – even into retirement and the final years of his life – remained a marketing man's dream. Even in his 50s, people wanted a piece of him. And when his life was at crisis point, there were always people there, willing to bail him out.

For most of the 1980s, he was at war with the taxman, over an initial bill for £16,000 which eventually made him bankrupt until Bryan Fugler, a London-based solicitor, came to an arrangement with the Inland Revenue and put a structure on the repayments. Then he went back to his roots, asking the people of Northern Ireland for help. They answered his call, raising £72,000 in a testimonial match and dinner, which got rid of the wolf as well as the taxman from his door. "The people of Belfast have sorted my whole life out," he said.

Albeit temporarily. He continued to have struggles and yet continued to be loved. A drink-driving charge in 1984 brought him to Southwark Crown Court to appeal against a prison sentence. McIlvanney and Jeff Powell – two journalists – were asked to be character witnesses to which McIlvanney hilariously opined: "Having us on your side might make you the first man to be hanged for a driving offence."

The noose didn't come but prison did. Two months in jail were the longest two months of his life.

"I have had a great life," Best said. "I didn’t want to go to prison, I didn’t want to get banned from driving and I didn’t want to get involved in the fights. But it’s all a learning process that you have to go through."

The learning process and the life ended 10 years ago this week. The name and the legacy lives on, though. George remains Ireland's Best.

![Best stepping off the plane following a famous win over Benfica [Piture: Getty]](https://media.irishpost.co.uk/uploads/2015/11/George-Best.jpg)

![An Outstanding Contribution to Sport Award was posthumously awarded to footballer George Best and accepted by his son Calum Best at the 2015 Irish Post Awards [Picture: Malcolm McNally]](https://media.irishpost.co.uk/uploads/2015/10/BestAward-n.jpg)