GARY BREEN remembered being one of the boys of summer, one of the thousands who’d join the annual exodus, migrating back to where his parents had come from.

He remembered the bus journeys, out of Victoria, then out of the city and into the countryside, through the midlands and across the border to Wales.

Year after year, he made that journey with his mother and sister, first at Easter, then when school broke up. “Dad couldn’t come with us, he’d work.”

So dad missed out on the ‘awful stench of sick and drink’ on the crossings from Hollyhead to Dublin.

He missed his little boy looking out the window of his uncle’s car as they sneaked their way through the city centre traffic and then through the small villages and towns with their quaint little streets and funny little spellings.

Naas – ‘its Nace not Nasss’ - was one of the easier ones. Portlaoise and Borris in Ossary took a few attempts before the pronunciations were perfected. Then it was Limerick, Ennis, Kilrush and finally, Cross, just outside Kilkee in Clare.

That was his mother’s home – Beaufort, outside Killarney, his father’s. Eight weeks a year he’d spend there, taken in by his grandparents, homes filled with love …. and cups of tea. Long before Sky News had their news on the hour, every hour, Irish society had its own regular 60-minute update, with the sound of a boiling kettle in the background, gossip in the foreground.

He smiles at all that, three decades on. Approaching middle-age now, Gary Breen’s childhood story could be told by thousands of second generation Irishmen.

Certainly it resonated with David Connolly, Lee Carsley, Steven Reid and Kevin Kilbane when he became an Irish international.

Over the course of a decade, he’d be reminded of those trips back ‘home’, of the looks on their London friend’s faces when they’d tell them about open 'red' lemonade. “How is it red?” they’d ask. “And I never knew what to say,” Breen smiles.

Then on this day, June 1, 2002, he was speechless again. “I’m not an emotional person but that day I felt huge emotion,” he said. The day was Saturday, Ireland’s opening game in that year’s FIFA World Cup.

Fans celebrate Gary Breen's goal in the Allsport Cafe in Temple Bar, Dublin during the 2002 World Cup Ireland V Saudi Arabia game Picture: INPHO/Patrick Bolger

Fans celebrate Gary Breen's goal in the Allsport Cafe in Temple Bar, Dublin during the 2002 World Cup Ireland V Saudi Arabia game Picture: INPHO/Patrick Bolger“We walked out the tunnel, saw the sea of green and there and then, I just thought back to all those summers, to mum and dad, to going back home, to growing up.”

Strange things came back to him, the tears of his grandparents when they kissed him goodbye at the end of the holidays, the contrasting sounds of Clare and Kerry to Camden Town, where he grew up, the Sunday afternoons in the Irish centre on Murray Street, just off Camden Road.

“Dad would be inside, and if it was dry, I’d be outside, kicking a ball against a wall, waiting to head home.”

It was there he learned about a different Ireland, the one beyond the 32 counties, where old men gathered to watch, or talk, about the football back home. He’d learn about his great grandfather, Patrick, who played in the 1914 All-Ireland with Kerry.

Other boys from St. Aloysius, his school, would go there too, Irish kids with their Cockney accents who were certain of their identity.

Which is why he doesn’t get the thing with international rugby, where a player can switch allegiance after three year’s residency in another country. “It isn’t right. International sport is special. You have to protect it.”

And though he’s too polite to say it, he couldn’t quite get his head around the whole Jack Grealish saga, either. “By 16, you know what you are. I know I did.”

Damien Richardson knew too. A Dubliner, who was then in charge of Gillingham, he called to the Breen family home one day in 1992 And sat in their Irish living room with the noise of London buses passing by on the street outside, and sold the dream.

“And mum bought it all,” Breen laughs. Richardson had two cards to play – the nationalist one for the parents, the first-team one for the player.

“Sign for us, Gary, and you’ll play first team football,” he said.

“More tea, Damien.”

“Go raibh maith agat Mrs Breen."

Breen signed, Richardson kept his promise and soon after, an international manager was on the phone. “Gary,” Richardson said, “the England Under 18s want you.”

Unimpressed, Breen stared at Richardson before asking: “Damien, don’t you know me?”

Soon others would learn about him. He’d move from Gillingham to Peterborough, Peterborough to Birmingham, Birmingham to a Coventry side who were then in the Premier League.

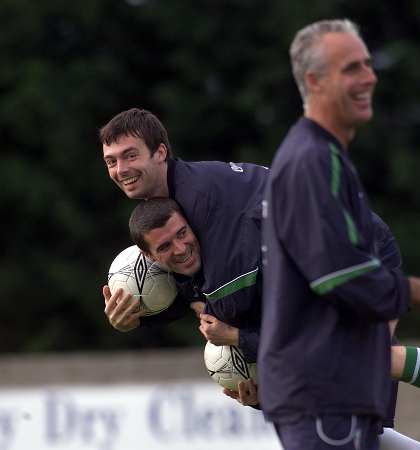

Pictured in 2001 at a Republic of Ireland training session with Roy Keane and Mick McCarthy. Picture: INPHO/Andrew Paton

Pictured in 2001 at a Republic of Ireland training session with Roy Keane and Mick McCarthy. Picture: INPHO/Andrew PatonAnd by now he was established in the Ireland team, heading to a World Cup in Japan and Korea, via this small, idyllic island in the middle of Pacific called Saipan.

Even now, 14 years on, he’s reluctant to say too much about what happened in those fateful days, when Roy Keane, the team’s captain and best player, clashed with Mick McCarthy, their manager.

In the first of his autobiographies, Keane namechecked Breen as being one of two players who came to his room to see how he was and say how sorry he was that he was not going to the World Cup.

A few months later, after the book was published, I spoke to Breen about that passage in the book and sternly he said he hadn’t read it, before subsequently, his tone softened and he quietly said: “The whole thing is too sensitive to talk about.”

And that’s how it remains: “It was such a massive disappointment and always well be,” said Breen of the fall-out. And it wasn’t the only regret. “Had we beaten Spain [they lost on penalties in the round of 16], we could have reached a World Cup final.”

The confidence he felt that summer was never again replicated. On the pitch, he played superbly, easily the best football of his career, and off it, he was serenaded by a chorus of Irish fans who worked his name into a new anthem. “We all dream of a team of Gary Breens,” they sang.

He loved it. Then, as time passed and his career came to an end – ‘I knew when it was time to go, cos when I was breaking through I could see lads who were hanging on in there and I thought, ‘no, don’t cling on. When the time is right, go.’ So in 2006, a decade after breaking in, he walked away.

That was when he should have been forgotten about, when new players should have had their songs of praise. But as the years passed and one campaign after another ended in failure, something strange happened.

The soundtrack of 2002 became popular again and “We all dream of a team of Gary Breens,” could be heard from the Irish section of grounds at each and every game.

With typical self-effacement, he smiles at the irony: “Well, a team of Gary Breens isn’t going to win many games of football.”

But he believes there is a warmth to the fans’ song. “It’s about their memories and adventures of that summer and the fun they had. I smile every time I hear it sung.”

When the music stopped at the end of his career, he adjusted easily, he says, to the sporting afterlife, settling firstly into the world of coaching, then into punditry.

“I didn’t want to coach an Under 21 team. I wanted a side where the players’ relied on victories to pay their mortgages.” That meant Barnet and Peterborough. Tough jobs. “But enjoyable ones. I liked working with players, figuring out ways to make them better.”

These days, though, he earns his money from the studio of Setanta Sports. A considered and clever pundit, his appreciation for the game’s tactical trends is evident every time he speaks.

Yet this summer, he won’t be working from France. Instead, he’ll be in Paris, Bordeaux and Lille as a fan, sitting among the Irish section, dreaming of a team of Gary Breens.