THE use of the word ‘hun’ to describe Rangers fans has come under fire recently, as have two journalists that have used it.

Both Jane Hamilton from the Daily Record and Irish Post freelancer Rachel Lynch caused Twitter storms (Lynch has now privatised her Twitter account) after receiving a torrent of abuse for their controversial tweets, including some in Lynch's case from 2012 in which she used the word ‘hun’.

Lynch told The Irish Post that her understanding of the word was it was not sectarian, but added: "That said, the tweet was in 2012 and I haven't used the word since..."

But what are the origins of the word in relation to the Glasgow club and is it offensive and sectarian, or merely a derisive but innocuous term for the opposition?

I’ve come across several theories put forward by Celtic and Rangers fans as to its origins, albeit on that most dubious of sources that is the football web forum.

Could it be that Rangers players avoided the front in WWI by taking jobs in shipyards and were described by critics as being no better than the 'huns' (Germans)?

Or perhaps after Harland & Wolff (co-founded by German Gustav Wolff) acquired a shipyard in Govan in 1912, Catholics were discouraged from working there? Then, with the onset of WWI, the term was used to describe the Govan-based, Rangers-supporting workers at the part-German owned firm.

It might be because Rangers fans are proud of their British identity, and with the Queen descendent from the German House of Wettin, her Rangers-supporting subjects are called ‘huns’ by the largely Catholic fans of Celtic, a club with strong Irish links.

![Rangers fans are generally proud of their British heritage [Picture: Getty]](https://media.irishpost.co.uk/uploads/2016/06/Rangers-fans-N.jpg) Rangers fans are generally proud of their British identity [Picture: Getty]

Rangers fans are generally proud of their British identity [Picture: Getty]Theories are ten-a-penny – there are even suggestions that Rangers fans initially called Celtic fans ‘huns’ because of Irish Republicans’ support for Nazi Germany, and that it was chanted by fans of both teams when the losing side’s supporters were spotted leaving early: “Go home you huns…” One Hibs fan wrote that he recalled singing the same refrain no matter who the visitors to Easter Road.

Another popular theory is that the term was used by an English newspaper to compare Rangers fans to “marauding huns” — the nomadic, devastating military force infamously led by Attila in the fifth century — when they ran amok while in town for a match.

However, I have seen the location of the chaos variously identified as Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Newcastle and Sunderland. While there exist reports of visiting Rangers fans’ anarchic behaviour in English cities throughout the decades when in town for friendly and European fixtures, I have yet to see any evidence of this ubiquitously cited “marauding huns” quote.

One paper that does use the word is the Glasgow Herald. Their August 12, 1983 edition includes a letter from a reader recalling a Cup Final at Hampden when, ironically, both sets of fans were united in a rendition of Go Home ya Huns over their disdain for the half-time entertainment — a display of Pakistani dancing.

In January that year, the same paper also reported the use of the word by Celtic fans, though Rangers fans appeared to give as good as they got and no one seemed to go home offended.

In a lighthearted piece comparing a Rangers vs Celtic game to the Scottish Baroque Ensemble’s inaugural New Year’s party in Edinburgh, Tom Shields wrote:

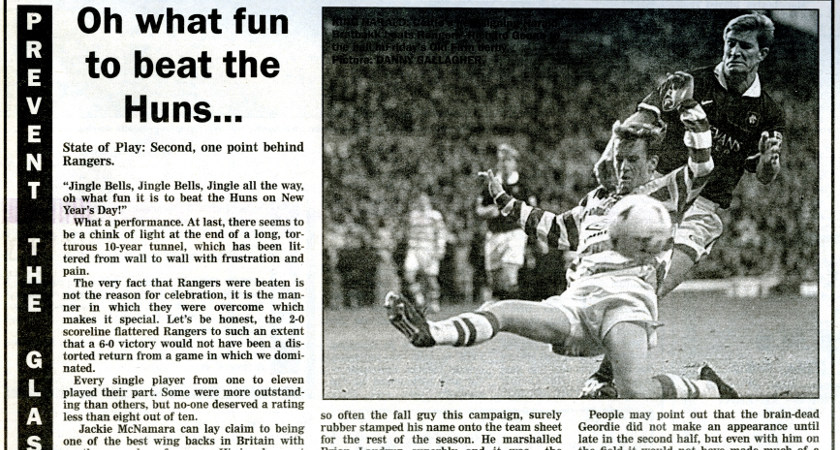

The Celtic fans, who had been advised by their club newspaper to restrict their songs and chants to those of a relevant nature, gave a spirited version of Jingle Bells which ended with the line: ‘Oh what fun it is to **** the Huns on New Year’s Day.’ The Rangers fans meanwhile, took such comfort as they [could] find in a little ditty to the tune of Home, Home on the Range. This went as follows: ‘Oh, no Pope of Rome, no chapels to sadden the eye, no nuns and no priests, no rosary beads, every day is the 12th of July'.

He added: “Despite the expletives, it must be said the Old Firm fans are more civilised in the Ibrox environment. I even heard a Rangers fan, who had spent most of the match describing the opposition as a Fenian ****, praise the Celtic team. After Charlie Nicholas’s goal, the fan said to his neighbours: ‘That was a good goal. What a player that boy is.’ Then, sensing the grief and despondency around him, he added: ‘But don’t get me wrong, I hate the **** as much as anybody.’”

Fifteen years later, The Irish Post itself used the term, again referencing the aforementioned song in a report on the traditional New Year’s derby match. Today, as the editor confirms, it has no place in our paper or on our website.

It seems to have been a derisive but inoffensive term for the club and its fans until the turn of the millennium, having previously been used by fans of both clubs — and other Scottish clubs — in previous years.

The label seems to have stuck with the Ibrox club though, but in the last two decades has it come to mean more than just a snide slang term?

When I was a young Celtic fan in Belfast, having previously only heard the term in reference to WWI German soldiers, I always believed its use was a way to describe Rangers as the enemy.

We, Celtic, were the Allies, while Rangers, our rivals, were the 'huns', one of the Central Powers and the villains of the piece. However, in that same city, there was no escaping the fact that 'KAH' (Kill All Huns) graffiti was a very clear attempt to link the word to the largely Protestant unionist community, nor was the sentiment of said graffiti a cordial one.

In 2001, Celtic itself blocked fans from their website for using the word, with club administrator John Cole saying at the time: "It's a word that can cause offence and at Celtic we don't want to be offending anyone.”

Rangers fans also claim that the more recent use of the word by Celtic fans to also describe Hearts — ostensibly perceived as Edinburgh’s ‘Protestant’ team — indicates that the term is now sectarian. Scottish anti-sectarian charity Nil By Mouth describes the word as “sectarian” and “abusive”, adding that it is “used negatively against Protestants”.

In recent years, individuals have also found themselves in hot water over the use of the term. Two Celtic fans wound up in court after unfurling a banner with the word ‘hun’ on it in 2010, charged with breaching the peace aggravated by religious prejudice.

However, the court returned a verdict of not proven. Former Celtic player Gerry Britton, lawyer for one of the men, said: “Our argument was that the word ‘huns’ may be none too pleasant, but is not a religious comment.”

Former Celtic striker John Guidetti meanwhile was found guilty last year by the SFA of “making comments of an offensive nature” after reciting a song featuring the word while being interviewed on Dutch TV.

![Former Celtic striker John Guidetti got himself in hot water for using the word [Picture: Getty]](https://media.irishpost.co.uk/uploads/2016/06/John-Guidetti.jpg) Former Celtic striker John Guidetti got himself in hot water for using the word hun [Picture: Getty]

Former Celtic striker John Guidetti got himself in hot water for using the word hun [Picture: Getty]Last year Rangers fans began plans to lobby Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to have use of the word made illegal. An online petition — now closed — started last year as part of the campaign has since been thrust back into the spotlight after being picked up by publications including Metro and Cosmopolitan in recent weeks.

Research from the Scottish Government’s 2014 Social Attitudes Survey found that only around nine per cent of Scots found the terms 'hun' and 'Fenian' acceptable.

It’s pretty clear then that many Rangers fans and independent organisations now consider the word sectarian. It appears to have undergone a relatively swift and radical semantic change as while some now use it as a derogatory catch-all term for Rangers, Protestantism, Unionism etc, many — myself included — have always considered it to be solely a slang term for Rangers fans.

Like any designation, it depends on who is using it, who it is directed toward and in what context. But if, as appears to be the case, it is causing offence to a large section of society, isn't it time to relegate it to the past?