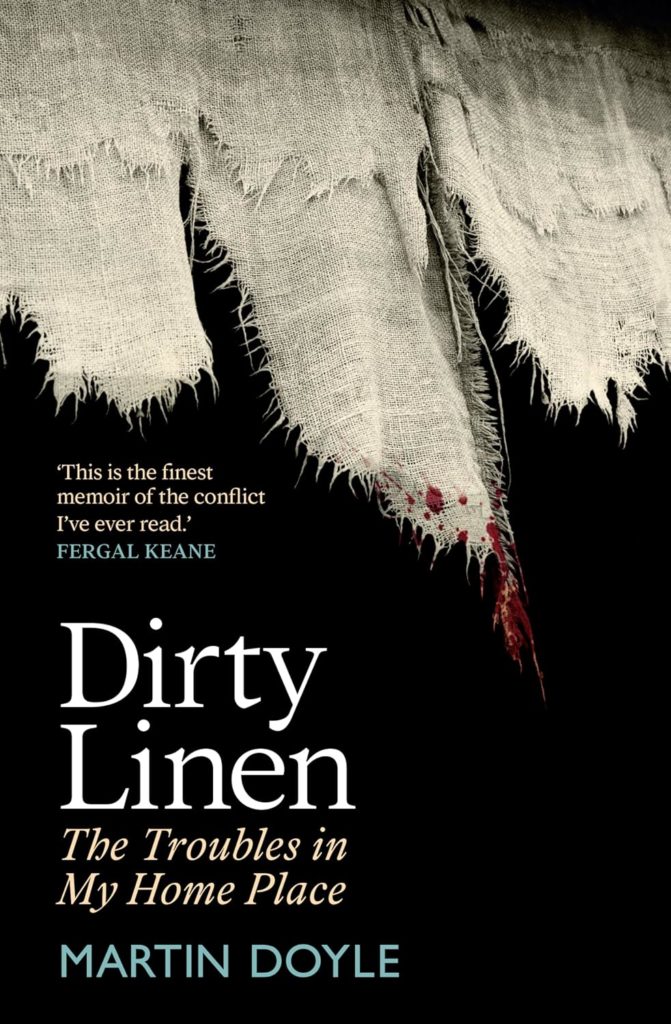

Former Irish Post editor Martin Doyle’s book Dirty Linen unmasks the dark past of Tullylish in Co. Down — but it is a small town story familiar throughout Northern Ireland

There is a type of conversation I have had many times with people in Northern Ireland.

Typically, we are talking about the Troubles and the other person says, “You know, I was never really affected by the violence. It never came home to me.”

Then they start telling you about near misses, work places bombed, neighbours killed.

Martin Doyle had been asked to write an essay for a collection of working class writing. He similarly didn’t think that much had happened around him until he took time to think about it. Then he started counting the murders close to his home and found twenty of them.

Dirty Linen is his return to his home parish, Tullylish, near Banbridge in Co. Down, to meet the neighbours who were bereaved and hear their stories. He gets the access only a neighbour could and the result is intimacy, compassion and detail in his accounts of horrific cruelty and enduring bereavement.

This is a good approach, to focus on one small area to illustrate the impact of the violence and the ubiquity of grief.

What we get is complex and engaging stories of family life, profiles of respected neighbours and their work. At the heart of each story is an atrocity, an ambush on a cottage, a policeman riddled with bullets, brothers shot side by side in their home, a premature explosion.

The families of the murdered knew each other and the damage is not just in shared loss but sometimes in the suspicions that arise from not knowing.

When the O’Dowd brothers and an in-law were shot dead in their home, gunmen had come so stealthily that they must have known the layout of the area, the gaps in hedges, the shortcuts.

When RUC man Robert Harrison was set up for murder, this involved a woman calling to make a false report that incendiary devices were in a shop. There was a lookout on standby to signal to the gunmen .

Relatives of the dead lived with the fear that people they knew and passed in the street had facilitated the murders.

This is quality journalism, memoir-led, starting on his own doorstep and expanding into a comprehensive, if local account of how division touched everyone. Doyle’s sources range from his mother, Mammy, to the archived details of IRA pensions from the War of Independence.

He draws extensively on literature too, to illustrate the character of the area and for guidance on how to respond.

He was empowered to empathise through his own grief for his wife Nikki who died of cancer. He says at the end that these people who suffered were his tribe, special to him.

Visiting scenes of past killings was like pilgrimage.

The area he draws on is the parish of Tullylish, situated in two triangles, the murder triangle in which the notorious Glenanne gang of loyalists operated and the linen triangle.

Doyle’s approach is a reporter’s. He talks to people and quotes at length their accounts of their experiences. He says in the beginning that he intends to hold his sense of humour in check, but thankfully he doesn’t wholly succeed in this, though when dealing with the families of the victims he is always respectful and attentive.

All of these killings will have been reported on at the time but rarely has any reporter spent so much time with the families of victims and heard their stories in such detail, and not just the stories of the attacks themselves but of the characters of the people lost, how they were loved, their quirks of character, from practical joking to religious observance.

Doyle also says he feels it is necessary sometimes to include gruesome details, because the glorification of IRA violence follows “if you allow a new generation to ignore the gore in which it is steeped”.

He says he made that decision after reading a LucidTalk poll which found that 69 per cent of Northern nationalists and republicans agreed with Sinn Féin vice president Michelle O’Neill that there had been no alternative to ‘violent resistance to British rule’.

The book is extraordinary.

More of his own life story coming towards the end is a bit of light relief. He says he had the option of a different life after university among the ‘yahs’, the toffs at St Andrews, but chose journalism with a special interest in the Irish community in England. This took him to working with the Irish Post and then becoming editor of this paper.

He has stories of his own direct experience of sectarianism. An example of his own was mitching school to pick potatoes and being stoned by the other pickers who caught on that he and his friend were ‘fenians’.

Paddy Kielty, the comedian, whose father was murdered, has said that life during the Troubles was not normal but not special either.

This contains an insight into why people are loath to talk about direct experience, the desire not to be special, perhaps not to be claiming particular sympathy or not wanting to upstage those who have suffered more, and there are always so many of them.

This is not normal life and death Martin Doyle describes here, but these are normal people still suffering and they deserve the special attention that he has given them.