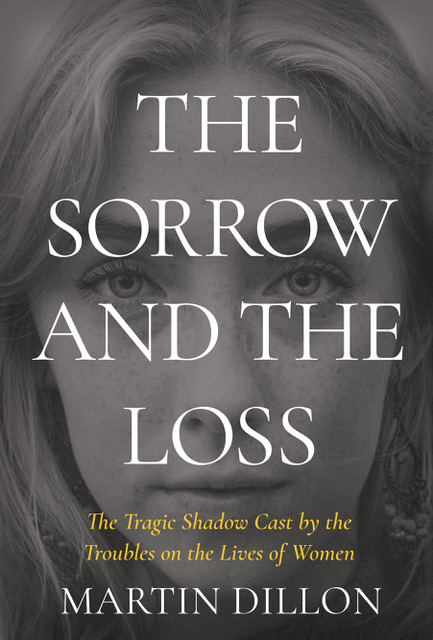

The shadow cast by decades of conflict and violence on the lives of women is explored by BBC journalist Martin Dillon

IN A NEW book In The Sorrow and the Loss — The Tragic Shadow Cast by the Troubles, award-winning journalist and bestselling author Martin Dillon explores the toll Northern Ireland’s bloody conflict took on women. Featuring previously unheard voices from both sides of the community and beyond, this book features a wide array of testimony: the wife of a high-level UDA assassin, the mother of a murdered RUC officer, a survivor of the 1974 Dublin bombings and more.

Dillon, the first person to expose the IRA policy of disappearing victims, delves into some of those brutal murders, including those of Jean McConville and Columba McVeigh.

Martin Dillon (75), who was born in the Lower Falls area in Belfast, worked as a BBC journalist for eighteen years, producing award-winning programmes for television and radio, winning international acclaim for his unique, investigative books on the conflict in the North. Conor Cruise O’Brien, the renowned historian and scholar, described him as ‘our Virgil to that inferno’.

In his book, through raw and compelling testimonies, Dillon explores the overlooked perspectives of mothers, wives, sisters and daughters, whose lives were brutally affected by the conflict.

Some were directly involved in violence as members of paramilitary organisations. Many witnessed the ruthless murders of family members. All were profoundly and irrevocably affected by the bloodshed.

Among those who share their stories are a survivor of the 1974 Dublin bombings, the wife of a notorious UDA assassin, and the daughter of a murdered judge, their words reverberating with the intensity of their experiences.

The story of the daughters of Catholic judge Rory Conaghan is told in harrowing detail.

Conaghan was assassinated by the IRA on 17 September 1974 in Belfast. The 52-year-old High Court judge was shot dead outside his home in the Malone area, an affluent suburb of the city that includes Queen's University. His murder came amid a wave of attacks on members of the judiciary and legal profession — the IRA viewed them as enforcers of British rule in Northern Ireland.

On the morning of his killing, Conaghan was leaving his home when gunmen ambushed him, shooting him several times. He died at the scene. His assassination sent shockwaves through the legal and political communities. His murder was widely condemned, with even nationalist politicians denouncing the attack.

In his book Martin Dillon writes:

“For the Conaghan sisters, the morning of 16 September 1974 was a typical weekday. They shared a family breakfast before going upstairs to their bedrooms to dress for school. By 8.30 a.m. Mary was in her room and Dee had gone downstairs. Suddenly, Mary heard what she thought was a bomb going off. She ran downstairs screaming, ‘Watch your eyes,’ believing the major risk to her family would be flying shrapnel. Her response was emblematic of the reaction of a young girl who lived in a violent city. When she reached the hallway, she saw her father lying on the floor and Dee standing over him.

“Judge Conaghan had heard the doorbell ringing and thought Mary must have already left for school but was returning because she had forgotten something. He opened the front door with Dee by his side. They were confronted by a man dressed in a standard General Post Office jacket with a badge on his lapel bearing the number 288. Over his shoulder was a postbag.

‘Is this Mr McGonigal’s house?’ he asked.

“Before Conaghan could reply, the bogus postman drew a gun from his bag, shot the judge at point-blank range and ran off. . . . . Decades later, in an interview with Irish Times journalist Róisín Ingle, Mary recalled, ‘As the gun came out, my father shouted at the top of his voice, “I’ve been done; call a priest!”;Judge Conaghan must have realised in that terrible moment that he was facing certain death.”

Dillon goes on to explain that the judge had been a liberal, well-intentioned man: “The IRA leaders who condemned Judge Conaghan to die in front of his young daughter did not know, or did not care, about his fairness or that he, like the other Catholic judges they were murdering, was a man of conscience and integrity. For example, before his death and much to the displeasure of the British government and unionist leaders, he awarded damages to sixteen Catholic men who had been arrested during the 1971 internment swoop and were subjected to unusual and degrading treatment under interrogation. Rory Conaghan judged everyone equally under the law, showing no favour to any grouping or individual. What the IRA did not understand was that men like Judge Press Copy Conaghan believed the judicial system required reform, which could be better achieved by working within it.

“The IRA condemned Conaghan’s daughters to live with the horror of witnessing the brutal death of their father. Some of the women I contacted when writing this book had similar experiences but found it too painful to recount their stories for me because revisiting the past would have opened raw wounds, bringing back terrible memories. Mary Conaghan, who later became a bereavement counsellor, acknowledged to The Irish Times that the pain never vanishes.”

This book is a gripping and deeply moving addition to the ever-expanding canon of literature on the Troubles, offering a meticulously researched accounts of some of the most horrific incidents of the Troubles — from both sides of the political divide.

Through a blend of historical analysis and personal narratives, the author paints a picture of the climate of fear that gripped Northern Ireland during the years of conflict, and how that impacted on women — an aspect of the Troubles rarely explored.

What makes this book particularly compelling is its human focus—the impact of extreme violence on family. The writing is both journalistic and poetic, balancing cold, hard facts with an evocative portrayal of grief, resilience, and the devastating consequences of bloodshed and deat

The testimonies:

“I can’t understand why I felt ashamed, but the bombing was always referred to as ‘The Accident’...I called it an accident for so long and so did others. In 1998, after I had my eye removed and joined the group Justice for the Forgotten, I learned how the bombing was planned and carried out. Everybody referred to the tragedy as ‘The Accident’. I don’t know why.”

- Bernie O’Hanlon, who was scarred for life at sixteen years old in the 1974 loyalist Dublin bombings

“When I eventually lived with him, our home was raided a lot and it was very stressful. We didn’t have cameras back then, but we had an iron door behind the bedroom door. I was so gullible. I asked my daddy what was going on. He was worried that the IRA would come and shoot Stevie and I’m living there with him. I said, ‘Daddy, I always spread my hair over the pillow at night so if the IRA comes to shoot Stevie, God forgive me, I thought if the IRA sees my hair, they’ll know it’s me and not Stevie.’”

- Tracey Coulter, former wife of the UDA's Stevie ‘Top Gun’ McKeag

“It is terrible to think that my daughter’s remains were scattered across a field.’

- Jean Doak, mother of Tracy Doak, a member of the RUC killed by an IRA bomb in 1985 along with three of her colleagues.

“I told [my mother] I prayed for him every time I went to Mass and that was five days a week. I would always light a candle for him when I lit ones for dead relatives. She told me never to do that. “I should only include him when lighting candles for the living, as she did. She waited at home all those years for him to return.

“Her and my dad could not go anywhere together because she believed that there always had to be someone in the house in case Columba walked through the door.”

Dympna McVeigh, sister of Columba McVeigh who was abducted, murdered and secretly buried by the IRA. His remains have never been found.

In The Sorrow and the Loss — The Tragic Shadow Cast by the Troubles

Published by Merrion Press