ASIDE from international affairs, in these islands, the news agenda in 2017 was dominated by half a dozen or so events…

Cakegate

Seldom has a cake been at the centre of more attention than the ones not made by Asher’s Bakery in Belfast.

In May, under the stewardship of Daniel McArthur – a former member of the Free Presbyterian Church who now worships at the Trinity Reformed Presbyterian Church – the company allegedly refused to make an engagement cake for a gay engagement, with the slogan 'Gay marriage rocks'.

It came three years after the company refused to make a cake supporting gay marriage, sparking a legal battle.

This would have been in direct contravention of their Christian beliefs, Mr McArthur said. Every cake Asher’s Bakery makes is crafted to the glory of God.

He might as well, he said, adorn a cake with messages saying that God allowed him to covet his neighbour’s ass, despite the Ten Commandments prohibiting that very thing.

People in the rest of Britain were, frankly, baffled that a section of people, living under British jurisdiction, held to such Old Testament beliefs.

They shuddered, and hoped this would be the last they would hear of this weird sect.

The UK's highest court, the Supreme Court, will sit in Belfast for the first time in April 2018 to hear the final appeal from Asher's Bakery in the 2014 case.

The Election Result

The General Election polls seemed to indicate a huge landslide for the Conservatives, with the Labour Party probably ceasing to be. Bloody polls, eh? Coming over here and telling us how we’re going to vote.

But the polls got it hugely wrong.

Nobody, probably not even Labour supporters, had counted on a bearded man, past retirement age, appealing to the young, to the marginalised, to those hit by austerity.

Jeremy Corbyn is particularly well thought of in the Irish community for (a) his work with Irish pensioners (b) his foresight in realising that if you wanted peace in Ireland, you needed to talk to the people who were actually doing the fighting.

Despite the best efforts of sections of the British press to connect Corbyn with the IRA, slowly and surely his popularity with the electorate increased.

Party time

Jeremy Corbyn did what few people suspected was possible: he denied Theresa May a majority in the House of Commons.

In doing so he came within a whisker of becoming Prime Minister himself. In terms of vote share, it was the closest result since 1974.

None of the other parties made any inroads among the electorate; if they had, Britain would have had a new tenant in Downing Street.

The state of the parties

■ Sinn Féin won seven seats, an increase on the 2015 tally of for seats. They still refused to take up their seats. Had they done so, Jeremy Corbyn might well have squeaked into No. 10.

■ The Liberal Democrats gained a few seats and lost a leader; in 1981 David Steel had told the Liberals to “Go back to your constituencies, and prepare for government!” This time they needed to be told to go back to their constituencies and think about getting a new leader.

■ Similarly Plaid Cymru, who made no real ground, more or less told their candidates to “go back to your constituencies and prepare for choir practice”.

■ The SNP lost seats. Oddly enough the seats were scooped up by the Scottish Tory Party, led by a gay woman who is married to a Catholic woman from Co. Wexford.

■ The Greens only returned one MP. Ironically, if you voted for the Green Party you wasted that piece of paper in 2017.

■ UKIP were eviscerated, polling less than two per cent. After all the rhetoric, they only managed to tie with low-fat milk.

Altitude sickness

In October Ryanair began cancelling flights. For a few days it looked like Europe’s largest carrier was teetering. The problem was down to rostering, and (arguably) not enough pilots.

But then Michael O’Leary got a Get Out Of Jail Free card (metaphorically speaking of, course, legal department please note).

Thompson Holidays went belly-up, and suddenly there were more pilots available.

Compensation was duly paid to the passengers who had found themselves stranded and unloved in airports many miles from human habitation.

However there were rumours that sincere apologies were being offered to passengers for the bargain price of £4.99.

Come on Arlene

Theresa May was returned as Prime Minister thanks to the 10 MPs of the Democratic Unionist Party, sometimes called the political wing of the Old Testament.

In something of a surprise to those living in Britain, these MPs represented an electorate, some of views that would embarrass a mediaeval serf — creationists, anti-gay, religious fundamentalists.

It was a surprise that some of them weren’t down at the town square throwing turnips at witches.

As one Irish commentator put it: “Congratulations to the English media on finally noticing that part of their United Kingdom is Alabama with umbrellas."

But these were the people, representing less than one per cent of the electorate of the UK, who now held the balance of power in Westminster.

When the Brexiteers said they wanted to “take back control for the British” they didn’t realise they’d be giving it to a party that nobody in Britain can actually vote for.

But, on the plus side — perhaps Northern Ireland can be a moderating influence on Britain’s two warring communities.

Election reflection

In a move that seemed down to errant, lost-with-all-hands stupidity, Theresa May called an election she didn’t need to. This was in the wake of a referendum that similarly didn’t need to take place.

Both set-pieces, both of which produced shock results, were hoped to be a cure for internecine fighting within the Tory party. Neither worked, and the law of unintended consequences swung into action.

Martin McGuinness (right) passed away in 2017 while Gerry Adams announced he would step down as leader of Sinn Féin (Image: Getty)

Martin McGuinness (right) passed away in 2017 while Gerry Adams announced he would step down as leader of Sinn Féin (Image: Getty)Changes at the top

In 2017 Gerry Adams announced that he was to step down as President of Sinn Féin.

Alongside his friend and colleague Martin McGuinness (who died earlier in 2017) he had changed the course of Irish history.

There was nothing to suggest in their early occupations that they would play such as pivotal role in ‘community work’ — Adams was a barman, McGuinness a butcher.

Over the years Martin McGuinness always acknowledged his previous role with the IRA, while Gerry Adams always denied being a member.

Unkind voices have said he’s off to become President of the Amnesia Society.

Whatever the exact details of Mr Adams’ previous career, one thing is certain: alongside Martin McGuinness he steered Sinn Féin towards what at one time would have seemed the impossible: sharing power at Stormont with the DUP, and turning the North of Ireland’s problems from military to political.

With the old guard now gradually slipping away, the leadership of Sinn Féin has passed to a younger generation, one in which nobody has the whiff of fertiliser under their fingernails.

Brexit (1) Brexit Brouhaha

During the year, watching Brexit from an Irish perspective was likened to seeing your neighbour torch their house and then remembering your own roof is thatched.

But as the full implication of Brexit began to sink in during 2017 — shrinking pound, rising inflation, higher prices, more expensive holidays, problems with the Pets’ Passport scheme etc – the British began to look very worried.

Brexiteers continued to put a brave face on matters. But their government simply didn’t have any coherent plan; it turned out that they really were making it up as they went along.

The New Yorker headline summed up Brexit very nicely: “British lose right to claim Americans are dumber.”

Brexit (2) Break for the border

The British Government certainly hadn’t thought about the Irish border.

Indeed, few people in the rest of the EU considered the problems of, for example, the people of Stranooden in Monaghan having to cross a hard border on their way to the bingo in Derryloose in Armagh on a Tuesday.

According to surveys, the Irish border had the lowest priority in public opinion in France and Germany of all the EU / Brexit topics.

But suddenly it appeared as if this 200-mile frontier, which crossed farms, ran through villages, and even, in one place, passed through a pub, could scupper all the talks.

The Irish were under no illusions: a hard border would mean the return of the hard men.

Everyone and their mother knew that the first border post to go up in Armagh, Tyrone or Derry would be dismantled shortly thereafter, probably with the help of Semtex.

Theresa May's government was propped up by the DUP, who signed a Confidence and Supply deal (Image: Getty)

Theresa May's government was propped up by the DUP, who signed a Confidence and Supply deal (Image: Getty)Brexit (3) Deal or no deal

Theresa May had given the DUP a bung of £1billion. She thought that would keep them happy. She was soon to find out otherwise.

In early December it looked like a Brexit deal was on the table, with people on all sides happy with a compromise on custom unions, tariffs etc.

Except for the DUP. They don’t do smiley faces. And they were particularly displeased with a deal that would see the six counties move imperceptibly closer to the Republic.

Theresa May was summonsed to the telephone by Arlene Foster. The DUP leader told Mrs May the deal was off. The prime minister’s humiliation appeared to be so complete that Orangemen would probably be marching to celebrate her defeat for centuries to come.

But by the end of the year a deal to allow talks to progress to the next stage was cobbled together. Theresa gave the DUP what they demanded: a promise that Northern Ireland would remain within the UK customs union.

She also gave the Republic what it wanted: a promise that the whole island of Ireland would remain effectively within the EU customs union.

The fact that it was a fudge of momentous proportions soon began to become apparent.

Suspicious circumstances

To date, the Garda Síochána Whistleblower Affair has accounted for an extraordinary haul of curtailed careers — two Garda Commissioners (chief constables of the gardaí) two Ministers of Justice, one Secretary General of the Department of Justice and one Tánaiste, or deputy Taoiseach; all ‘resigned’.

The affair centres round Sergeant Maurice McCabe who brought to light gardaí malpractice.

The police force subsequently became bogged down in scandal, with cover-ups, victimisation and wholesale misconduct coming to light.

Nobody would have been surprised if the gardaí had renamed their house magazine The Bad Apple.

The affair took its latest turn in November, when the Tánaiste, Frances Fitzgerald, was forced to resign after accusations that she had interfered in the case.

Her resignation was required to stave off a general election, which could have proved calamitous at a time when Ireland was at the Brexit negotiating table.

It’s said that a good police force is one that catches more criminals than it employs. As regards the Garda Síochána, the jury (unrigged, hopefully) is still out on this one.

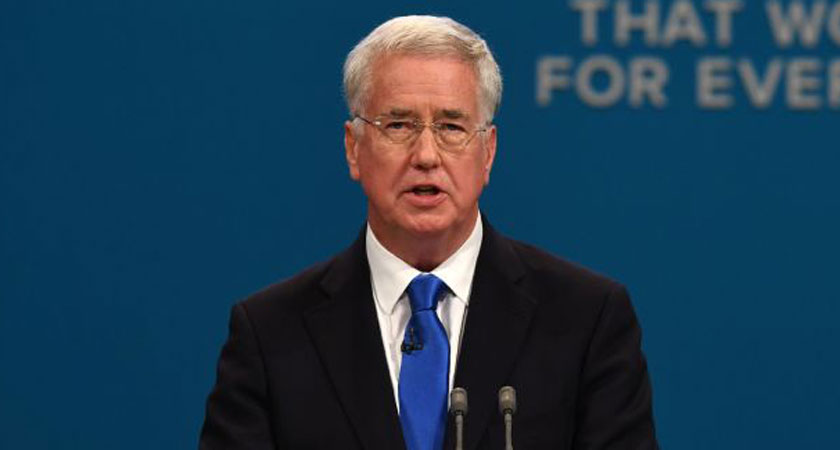

Pestminster

In 2017 Theresa May had much to contend with — the ongoing Brexit brick wall; a resurgent Labour Party; a strident Arlene Foster across the Irish Sea; a Taoiseach who was no pushover.

Her cabinet was riven by ideological differences and personal ambition: a junior minister, Priti Patel basically ran her own foreign policy, while a foreign secretary, Boris J, never read any of his briefs, sometimes with tragic results.

Mrs May even had to contend with a terror plot to assassinate her.

On top of all this, it transpired that a lot of members in the House had been unruly over the years.

It probably should have been no surprise. The Palace of Westminster has seven bars (all unlicensed), selling subsidised drink to many former public school yahoos, many miles away from their homes. ‘Vivacious’ behaviour was always likely.

Mrs May had to deal with the resignation of one minister, Michael Fallon, and an investigation into another, her de facto deputy prime minister Damien Green.

As Claudius puts it so succinctly: “When sorrows come, they come not as single spies but in battalions.”

That, as I am sure Mrs May knows, and you know as well, is a line from a tragedy.

The new Taoiseach

With the coming of the summer, Enda Kenny decided to call it a day. The man who tended to look as if he’d been asked to stand in for the Taoiseach at the last minute adjudged it time to collect his pension. The new man was Leo Varadkar.

As well as being Ireland’s youngest ever Taoiseach, Varadkar has scored many firsts: the first from an ethnic background, the first homosexual, the first doctor, the first person whose name is an anagram of “Olé aardvark”, the first to have the same name as both a former pope and a star constellation.

Leo’s accession meant that there were, for a short period of time, five ex-Taoisigh alive at the same time. Along with Leo Varakar they could have made up a fine poker game.

It’s hard to say who would have won, but the smart money would probably be on Bertie Ahern.