THE London Evening Standard’s Melanie McDonagh described the book Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922 as genuinely important; a must-read if you want to take the conflict between Britain and Ireland this time last century seriously.

It argues that Britain allowed the threat of violence to trump the democratic politics of Home Rule and so laid the foundations for the conflicts that followed. As such, she says “it was a book that makes me really, really angry”.

This is just one of the many enthusiastic reviews for Professor Ronan Fanning’s recent tome Fatal Path, which was also nominated for the 2013 Bord Gais Energy Irish Book Awards.

Here Dr Ivan Gibbons interviews the veteran historian, who will talk about his acclaimed new book at the Embassy in London this week.

IG: I notice that Fatal Path is dedicated to your ‘English mother and Irish father’. What is the significance of this?

RF: My son always says that my capacity to see both sides of the Anglo-Irish dispute can be attributed to my mixed parentage. My brother regards himself as English but I believe you can’t be half anything!

I was born and brought up in an independent Ireland so I consider myself Irish. However, I understand completely how someone born and raised in Northern Ireland can see themselves as both British as well as Irish.

When I retired as Professor of History at University College Dublin I continued as Director of Archives there. My job was to seek out possible collections for the archive.

Notable recent additions include the papers of senior Irish civil servant Dermot Nally, the equivalent of Sir Robert Armstrong in the British civil service, and who was responsible on the Irish side for the preparatory work which led to the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985.

I also secured the acquisition of the papers of the Progressive Democrats for the archive.

In addition, in my role as member of the Board of the Dictionary of Irish Biography I was responsible for many of the biographies of twentieth century Irish political leaders including Eamon de Valera, Sean Lemass and Richard Mulcahy.

Mostly though, I am now free to pursue my own writing and research of which Fatal Path is the latest example.

I find it extremely ironic that someone who was long regarded as a revisionist Irish historian is now stating, as you do quite clearly in Fatal Path, that without violence or the threat of violence British government policy on Ireland would not have moved beyond the Home Rule proposal of 1912.

Professional historians use the term revisionism sparingly to mean revising our knowledge in accordance with new evidence unearthed or old evidence revisited.

In Irish history revisionist is used as a term of abuse much like Marxists used it to vilify those departing from the party line. I never bought into the Provisional IRA’s interpretation of Irish history in which the revolution of 1916 to 1921 was great and glorious.

Having said that, I have sharp differences of opinion with other “revisionist” historians such as Roy Foster and Charles Townshend.

For example, I believe that Neil Jordan’s film on Michael Collins, by and large, got it right. Bloody Sunday and the start of the intelligence war in November 1920 changed everything as did the Kilmichael ambush the same month.

From then on the British realised that the war would not be over soon and thereafter there was no more talk of “having murder by the throat” in Lloyd George’s boastful phrase.

Neil Jordan wrote and directed a biopic about Michael Collins in 1996

Neil Jordan wrote and directed a biopic about Michael Collins in 1996Can’t the same argument that the British only react to violence or the threat of violence be applied to the recent Provisional IRA campaign?

Yes, of course.

Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s Chief of Staff, saw the typescript of Fatal Path and remarked that the analogies between 1921 and the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 were extraordinarily close.

At the time I was writing articles for the Sunday Independent urging talks with the IRA to go ahead. For this I was attacked by my fellow columnists, Conor Cruise O’Brien, Ruth Dudley Edwards, John A Murphy, Michael McDowell and Eoghan Harris.

What they didn’t know is that John Hume had shown me the notes of the clandestine meetings he was having with Gerry Adams at the time.

That is why I wrote what I did in the Sunday Independent. To his credit, of my fellow columnists, only Eamonn Dunphy afterwards admitted that I was right and they were wrong.

I found Fatal Path a profoundly depressing book. Nobody comes out of it well. You describe how both Asquith and Lloyd George vacillated and procrastinated on Ireland as they did not want to imperil their political position at Westminster. But isn’t that what all politicians do?

Quite right! Putting issues on the long finger IS what politicians do.

Their default mode is to procrastinate, putting decisions off until tomorrow if there is any danger of risking their parliamentary majority.

Both the Third Home Rule Bill in 1912 and the Government of Ireland Act in 1920 were massive exercises in hypocrisy. Asquith never expected Home Rule to be enacted in the way it was proposed.

And Lloyd George never expected Sinn Fein to accept the legislation setting up two Home Rule parliaments in 1920.

Lloyd George’s overriding concern in 1920 was to get the Ulster monkey off his back and to proceed only as far as his Conservative colleagues in his Tory-dominated coalition government would permit.

The GPO in Dublin has been the setting for official commemorations of the 1916 Easter Rising

The GPO in Dublin has been the setting for official commemorations of the 1916 Easter RisingIt seems from your book that Irish nationalist politicians had a naive myopia as regards the good intentions of British Liberal politicians and that John Redmond, in particular, was taken in by both Asquith and Lloyd George.

The problem from the British point of view from the 1880s onwards was Ulster. British Liberal governments were prepared to give self-government to the south or nationalist Ireland but were not prepared to allow nationalist Ireland to control the north.

On this the Liberals and the Conservatives were as one. It should also not be forgotten that the Liberals could be as anti-Catholic as the Conservatives.

For example, on denominational education which the Liberals with their nonconformist background were vehemently against, the Irish nationalists and the Tories were in agreement as in Ireland this would mean Catholic education and in England Anglican education.

The same applied to licensing legislation: The Liberals were very disapproving again because of their nonconformist temperance background whereas the Conservatives needed the financial support of the large brewers- “the beerocracy”- in the same way Irish Home Rulers were heavily dependent upon publicans in Ireland so that both were more sympathetic to relaxation of licensing regulation.

Asquith in 1912 was dependent upon Irish Home Rulers for his parliamentary majority so postponed any potential politically embarrassing resolution of the intractable Ulster issue.

The Ulster Unionists, as long as they could use the processes of parliamentary democracy to defeat Home Rule were quite content to do so.

Remember that Gladstone, despite his messianic mission to resolve the Irish problem was not competent enough to get the first Home Rule bill even through its first reading in the House of Commons in 1886 and the second Home Rule bill foundered in the House of Lords in 1893.

So Gladstone fell at the first hurdle leaving young ambitious Liberal politicians such as Asquith politically frustrated for the next twenty years as the Liberals kicked their heels in opposition –no wonder he wanted to avoid Home Rule destroying his government as well!

Only in 1911 when House of Lord’s reform threatened the Ulster Unionist position did things change. Carson wanted to exploit Ulster Unionist intransigence in order to defeat Home Rule throughout Ireland.

When the Home Rule Act was passed in 1914 there was no amendment for Ulster and Redmond agreed to postpone implementation for the duration of the war if the Act could at least be placed on the statute book.

Like all his contemporaries, Redmond’s concept of European war was the Franco-Prussian war of forty years previously- bloody but brief. If Redmond had managed to negotiate immediate implementation of Home Rule with exclusion of Ulster for ten years after the end of the war he at last would have gained power and patronage.

The Home Rulers were a millennial one - issue party and by the end of the war they had nothing to show for their thirty year campaign.

Wreaths lie on the memorial at the launch of an exhibition entitled Third Home Rule - The Unionist Response in November 2013

Wreaths lie on the memorial at the launch of an exhibition entitled Third Home Rule - The Unionist Response in November 2013In your book you make a statement that will shock many Irish nationalists – you state that in the 1920-21 settlements the Irish Free State was the bit left over once the Ulster issue had been resolved. This is a complete reversal of the traditional interpretation.

This was undoubtedly the case and the reason it is a shock is because southern nationalists have always underestimated and failed to recognise the Ulster Unionist case for the same right of self-determination that nationalists demanded.

On this, the Liberals and Conservatives were as one in not being prepared to coerce Ulster Unionists.

You state that revisionism as practised by some historians means history rewritten not as it was but as they would prefer it to be. In the Irish context this includes the belief that Home Rule could have been established as a peaceful transition to independence thus avoiding the trauma of violence. Do you believe that this could have happened?

No – here I part company with colleagues such as Roy Foster and with former Taoiseach John Bruton who hung a porttrait of John Redmond in his office.

The fact is that nationalist Ireland had been peacefully and democratically calling for Home Rule for thirty years without success. Therefore the democratic process did not work.

The first threat of violence came from the Unionists and this is what converted nationalists such as Eoin MacNeill and Patrick Pearse from Home Rule to a more militant nationalism.

If there had been no First World war and there had been a commitment to avoid violence then some compromise involving the exclusion of Ulster from a Home Rule parliament may have been possible.

Why do you believe that some Irish nationalists do not regard what happened between 1916 and 1922 as a revolution?

There is no question that it was a revolution. Power changed hands massively. Some doctrinaire republicans such as Cathal Brugha and Mary MacSwiney refused to accept this as a revolution as links remained with Britain.

Collins was more pragmatic but many republicans cannot or will not give credit for what was achieved in 1922. Socialist republicans say it was not a revolution because of the absence of any socialist component.

In this context, it is worth noting what Arthur Balfour – “Bloody Balfour” in his role as Chief Secretary to Ireland in the 1890s- said about the Irish Free State.

It was his belief that the new Ireland in 1922 was the Ireland that the British Conservative Party had created with its land acts and land settlements; its structure of local government and with the social revolution having been completed twenty years previously.

That’s why socialist republicans don’t like the Irish Free State settlement.

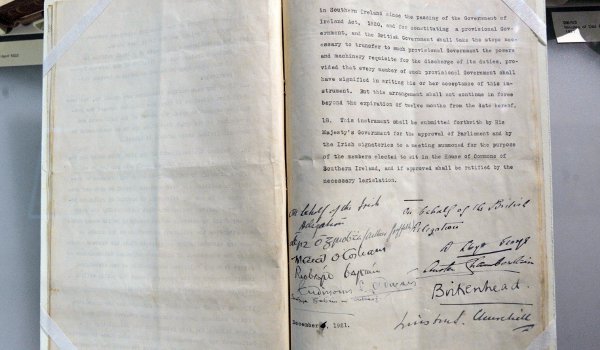

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921I notice that in your book you are highly critical of the quality of the Irish negotiators during the talks that led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921.

They were hopelessly out of their depth – particularly Arthur Griffith. Can you imagine during the talks with Tony Blair that led to the Good Friday Agreement Martin McGuinness saying to Gerry Adams “no matter what you do Gerry I am going to agree anyway”?

Yet that is exactly what Griffith said to his fellow Irish negotiators in 1921. It was a combination of vanity and total disaster.

I showed the typescript of the chapter on the Treaty negotiations to a diplomat friend who had worked closely on British-Irish relations in the Department of Foreign Affairs and his response was that he was both “embarrassed and ashamed” at how they were out-negotiated by Lloyd George.

Unionists in Northern Ireland today would take umbrage at your assertion that by introducing the spectre of violence into Irish politics their ancestors a hundred years ago triggered a process which led directly to the 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent Irish War of Independence.

If Unionists want to commemorate the foundation of the Northern Ireland state they should be commemorating the Larne gun-running in 1914, the threat to establish a Provisional Government in 1913, the mass rallies in Belfast and the paramilitary training not the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

The Somme is about the commemoration of sacrifice and nothing to do with the threat of violence that created Northern Ireland.

We are about to embark on the decade of commemorations between 1913 and 1922. I understand that you have reservations about this.

I certainly do.

There is a wide difference between commemoration and history. Commemoration is laudable from a utopian political perspective but history needs to remain objective and any commemoration needs to take into account other peoples’ point of view not to celebrate and upset others.

How do you think the 1916 Rising should be commemorated?

As the 100th anniversary of an event which led ultimately to a form of independence five years on but did not achieve anything at the time. It is commemorating blood sacrifice; if that doesn’t mean anything then 1916 doesn’t mean anything.

Will the 1916 commemoration be used to justify the philosophy and tactics of modern day Irish republicanism?

There is always that risk. I am vehemently opposed to the use of violence in politics but I recognise that it has been used in the past and when used against governments in parliamentary democracies it has worked.

Dr Ivan Gibbons in discussion with Professor Ronan Fanning, who was the keynote speaker at a recent MA Irish Studies conference St Mary’s University College.

Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922 is published by Faber and Faber, £16.99