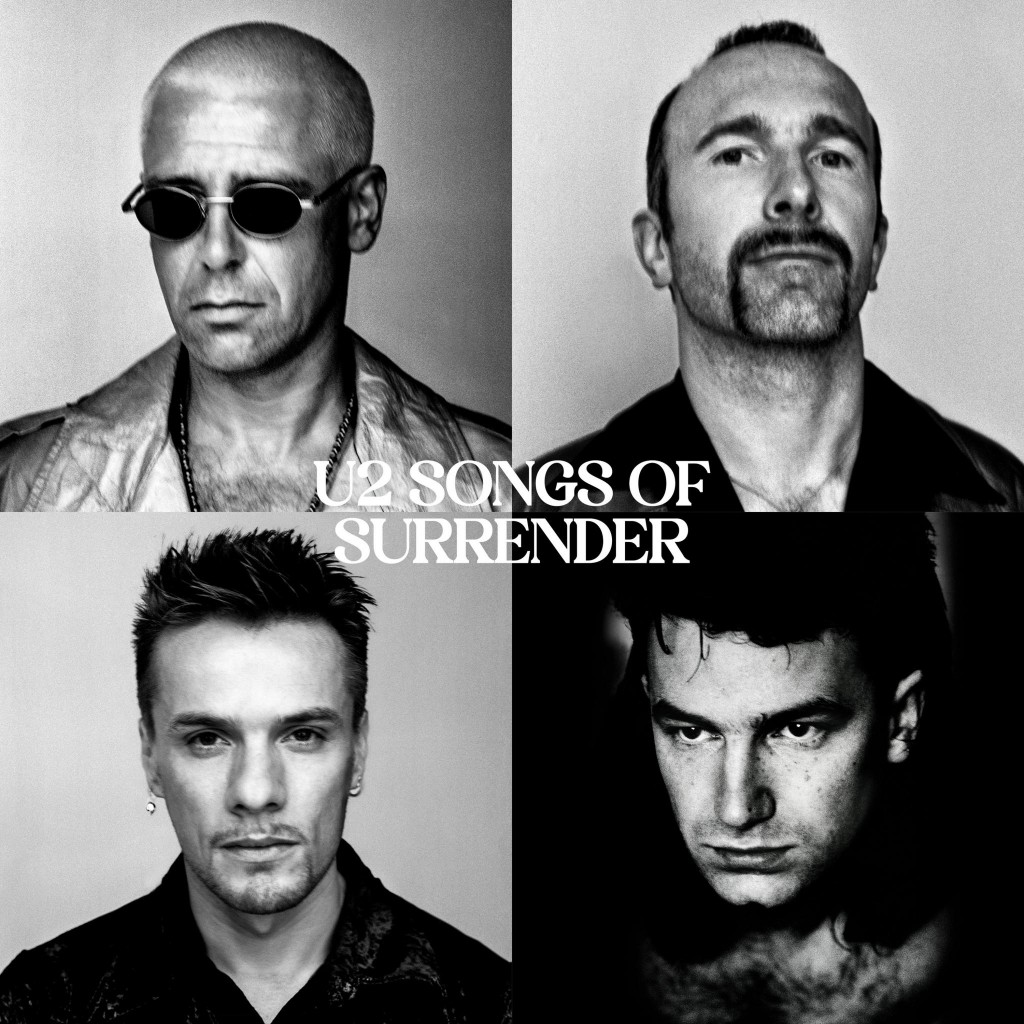

Tony Clayton-Lea reviews U2’s latest album Songs of Surrender

Songs of Surrender

Songs of SurrenderIt was, U2’s bass player Adam Clayton has implied, a relatively straightforward idea that turned into an intricate one. He is talking about U2’s new album, Songs of Surrender, which is now in your physical and online record stores. There was, once upon a time, something of a stir in the multiverse when a new album by Ireland’s best-known rock band was released. Queues would form outside your Virgin Megastores and your HMVs, and as the shops opened at midnight, the hunger of the culturally vampiric fanbase would be satiated. They would hold their newly purchased CDs close to their bodies, go home and play them until dawn. By the time they headed out to work, they’d know all of the songs.

Time passes, and things change, but the fanbase still knows all the songs by now, don’t they? Think again. As any clued-in U2 admirer is aware, Songs of Surrender may be the ‘new’ U2 album, but its 40 songs have been culled from their back catalogue to be revisited, refurbished, and recalibrated. Is it, you may ask, a back-to-basics exercise, a marketing wheeze to annoy the converted — that have many different versions of many of the re-imagined songs, anyway — or some kind of devilishly clever way of allowing U2 to re-think and regroup? The answer lies somewhere in between.

Songs of Surrender began not as an album but as a method of referencing the chapters in Bono’s 2022 memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story. Whatever songs were chosen had to have, by necessity of the book’s narrative flow, some level of self-evaluation. As matters progressed, however, so did the number of songs, and while the pandemic pulled the rug out from under too many people, for U2 it was time to breathe. We say U2, but it has emerged that the plan to reshape the songs was primarily the idea of Bono (aka Paul Hewson) and the band’s guitarist, Edge (aka Dave Evans). The outcome of such a notion is that the restructured songs arrive with only the most subtle of appearances of bass or drums on them and yet because they are so well-known within the context of rock music, they are as much U2 as they have ever been. The songs are one but they’re not the same? Cheesy and clichéd, we admit (somewhat embarrassingly), but it’s true.

The album is sectioned into four ‘sides’, one for each of the band, but that could well be a superfluous strategy to have us think the songs have particular meaning to particular people. While that may or may not be true, for the U2 fan the album in its entirety should work. All the band’s best-known songs are here. We won’t list all of them, but they include Beautiful Day, Where the Streets Have No Name, Out of Control, One, Bad, Stuck in a Moment You Can’t Get Out Of, Vertigo, City of Blinding Lights, I Still haven’t Found What I’m Looking For, Desire, Without or Without You, I Will Follow, and Sunday Bloody Sunday. We’d hazard a safe-as-houses guess that you’re familiar with the titles, but (quelle surpris) some of the renewed versions are almost unrecognisable.

A few examples: Stories for Boys and City of Blinding Lights are piano ballads; Every Breaking Wave is U2 as played by Erik Satie; Where the Streets Have no Name lays on a cushion of keyboards, Stuck in a Moment You Can’t Get Out Of is an acoustic strum; Sometimes You Can’t Make it on Your Own floats on fragile melody lines; Desire is funk as delivered in a high-pitched falsetto; I Will Follow is a twinkly retake; and so on. You can cross reference and compare, for sure, but throughout there’s little or no comparison between the bombastic weight of some of the originals and the nuances Bono and Edge have successfully managed to inject here.

Some artists rejig their back pages for various reasons. Bob Dylan doesn’t revisit his songs in the studio or on record, but he changes them every time he plays a gig, and has done so for decades; on her 2011 album, Director’s Cut, Kate Bush amended what she deemed to be problematical production issues and arrangements of past songs; more recently, Taylor Swift has re-recorded some of her early albums in order to escape restrictive contractual bonds. U2’s reimagining, however, is surely the most investigative and advanced. Across the album, they dig deep into their personal history; they tweak lyrics here and there; they confront what they view as past mistakes and try to correct them. It sounds as if they have snipped tie-wraps that have been around their wrists for at least 25 years, and it seems to connect with the problems they have been facing for the last ten years on the twin albums Songs of Innocence (2014) and Songs of Experience (2017): how to view their past through a present-day lens without coming across as creative navel-gazers.

The album is also the sound of a band that knows they have occasionally underachieved and that wants to make amends in small but distinctive ways. With the four members now in their early 60s, what they have done here — we are presuming, of course, that while the majority of the work was conceived and conducted by Bono and Edge, Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen Jr are in the mix, at least in spirit — is not so much a reinvention as a reflective rejuvenation.

Get it while it’s hot, too, because it won’t last long – Songs of Surrender is surely the final flick through U2’s back pages. According to the band, the next studio album will be full of intemperate, raucous and very loud rock songs. “We’re turning the amps on,” Adam Clayton recently informed Mojo magazine. “I certainly think the rock that we all grew up with as 16- and 17-year-olds, that rawness of those Patti Smith and Iggy Pop records… that kind of power is something we would love to connect back into.”

And so it begins. Again.