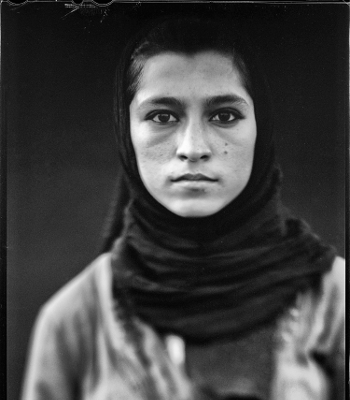

"WHEN I skateboard, I’m feeling like I am a bird," says Madina Saidi, her soft and pensive glare focused on the on-looking photographer.

"I feel free like I am flying. It is like I am above the war and not part of it"

A child, no more than eight-years-old, is transfixed by the sight of this slim and lively 14-year-old girl on a wheeled plank.

Overcome by curiosity, he approaches Madina and she takes one foot off the skateboard, carefully replacing it with his before racing him along the path that bisects a lush garden on Kabul’s Bibi Maru hill.

Beyond the two, there are several more children and several more skateboards, all wheeling along.

Laughter echoes into the photographer’s ears and the aroma of rosebushes wafts into his nostrils. His eyes, meanwhile, dash between the descending sun and the city below, which looks more like a blueprint than a busy and hazard-filled hub, before returning to the innocent playing.

This is not the first joyful scene that he has witnessed during his seven years in Afghanistan, but it is one of only a handful.

"It must be very difficult and challenging for you to go out without a burka or a male escort. What do people think of this?" he asks Madina.

“Oh, sometimes people shout bad words at me, but I don't care,” she replies, adding in broken English: “If the American people goes, I think the Taliban will come and the Taliban don’t allow me to go outside on the home.

"Then Americans should be here because they are good. They are good people. And I know that. If the Taliban come, I will leave my country.”

Irish photojournalist John D McHugh is not an overtly sentimental man. He is frenetic, impassioned, and – when talking about Afghanistan – often furious. But as he recounts this scene, shuffling towards the edge of his seat in London’s Frontline Club, the inflexion in his voice suggests that he is pained by it.

“There is a lot of misery and death that I have photographed. And that is the reality out there,” he explains.

“But this is also a reality. Even in the midst of everything that is going on, people strive to live their lives and they seek happiness.

“You do not hear kids laughing a lot in Afghanistan, but up on that hill, Madina was happy. And she was bringing a little joy to all the other kids up there."

As touched as he is by this scene, McHugh’s mood readily returns to one of frustrated anger as soon as his attention turns to the future of Afghanistan.

He is worried about what will happen to Madina Saidi and millions like her when NATO forces withdraw from the country next year.

He fears that they will come directly into the firing line of a bloody civil war. And by his own admission, there is no way he can mitigate that fear; he is too invested in the Afghanistan story.

For that reason, he does not want to talk about himself.

In particular, he does not want to talk about the day he was shot and nearly killed while embedded with a platoon of US soldiers.

“It will be six years ago in May, but it is still the only thing that people ever want to talk to me about,” he remarks, hinting at his disappointment in the West’s journalistic failings.

“I feel a certain responsibility to keep going back so that I can try and keep the story in the peoples' minds. Afghanistan is a sad story because an awful lot of money has been spent and an awful lot of opportunities have been squandered.”

When NATO forces bring their 13-year operation to a close next year, McHugh believes, there will be widespread bloodshed.

Ever-careful not to slip into hyperbole, he wants to clarify. He does not believe that the Taliban – or any of the other rarely mentioned factions – will seize power as they did in 1996.

Then he returns to his conviction: “I am very worried about Afghanistan post 2014. I think we are going to see a bloodbath.

That view, he adds, is common both among ordinary Afghan citizens and the many local experts, including the former Taliban envoy to the United Nations, whose everyday lives he has been documenting over the past year.

Referring to the Afghan National Army (ANA), a 260,000-strong infantry that is currently in the stuttering process of taking over responsibility for the country’s security, he says: “The situation could be even worse (than in Afghanistan’s previous civil wars) because now you have hundreds of thousands of men with military training and there are more guns in the country than ever before.”

McHugh’s impassioned pleas to bring attention to the country’s precarious situation and the signs of its malignant decline are made all the more furious by his belief that no-one is listening anymore.

Worse than ignorance, though, he argues that “lazy journalism” and the ill-conceived policy of “putting an Afghan face on the war” have combined to create a catch 22 situation regarding any news that does make it back home.

The only news stories that do reach the British and American public about life on the ground, he says, reaffirm one of two falsehoods; that the war is unwinnable or that the ANA is ready to take on the task of national defence and the NATO forces have done their job.

Either way, the 'it’s-time-to-leave-Afghanistan' message is perpetuated, while the awkward and convoluted truth about the country’s stuttering progress, as McHugh sees it, is smothered.

“The Taliban are extraordinarily good at convincing the British and American people that this war is unwinnable,” he says, restraining his otherwise frantic gesticulation to deliver a succinct claim.

“The best example of that is in their ‘spectacular’ attacks, like the recent strike on Kabul’s police headquarters. These achieve nothing in themselves because large numbers of insurgents get killed, they take no ground and they achieve nothing.

“But they are only designed to get coverage in the media back in the West, which has absolutely failed to report on Afghanistan in any kind of sensible way.”

McHugh adds that the under-estimated enemy is also adept at appropriating Western media in other ways as a platform from which to proclaim their message that time spent in Afghanistan is time wasted.

Asked to explain, McHugh cites the attack on a British base in Helmand last September.

“That was an extraordinarily daring attack by the Taliban that was brilliantly executed and they destroyed millions of dollars’ worth of aircraft,” he says.

“But the media jumped on the fact that (Prince) Harry was there and said it was an attack on him.”

That, he explains, opened the door for the more than willing “Taliban spokesperson” (his air quotes) to step in and claim that the attack had in fact targeted Captain Wales, which was reported and magnified the shock felt by British audiences.

“But it wasn’t an attack on Harry,” McHugh claims, becoming increasingly animated as his frustration grows.

“It was an attack on millions of dollars’ worth of equipment.”

His analysis of the reporting of green-on-blue killings is the same.

“In many cases, an Afghan has a row with an American and pulls out his weapon and shoots him.

"Then, the Taliban immediately say that they planned that for months. They did not, but that easy story gets reported because of lazy journalism.”

McHugh then diverts his stream of conscious frustration into “putting an Afghan face on the war”.

The policy, which is particularly popular among US forces, is simple: If any operation goes well, give all the credit to the Afghan troops, ostensibly to improve their morale, and make sure everyone sees you doing it.

Explaining that the otherwise valiant ANA lacks both supplies and planning capacity, McHugh said in a recent article: “Putting an Afghan face on the war means lying to the Afghans, lying to the Western public and sometimes, I think, the military are lying to themselves.”

But today, he is a more colourful mood.

“If I go and teach my little daughter how to ride a bike by putting stabilisers on it and tell her that she is able to do it all on her own and then I take the stabilisers away, she is going to fall and split her face open. And that would be my fault.”

He adds: “The Americans are constantly telling the Afghans that they are doing a great job and they are telling the world: "They got this. We're ready to go home." But they don't got this.”

Aside from the fact that a $4billion question mark hangs over the ANA’s funding, McHugh says that the army suffers from not having its own intelligence systems, air power or the capability to move wounded soldiers off the battlefield quickly in medevac helicopters.

Meanwhile, a bleak Pentagon report released in December found that only one of the ANA’s 23 brigades is able to operate without NATO support and supervision.

“I feel that a great disservice has been done to the Afghans in Afghanistan by the idiots who perpetuate the 'Putting an Afghan Face on the War' policy,” McHugh says, inflexion staining his voice again.

“It's going to be horrific when the West leaves, but everybody will say: "Well we gave them everything we could, if they're not prepared…" And that is wrong. They don't have everything.

“They clearly are not able to do this. And the only way that they're going to find that out is when lots of them die.”

If it were up to him, McHugh would put Madina Saidi’s face on the war.

Along with the rest of the members of Skateistan, an NGO founded in Kabul that provides skateboarding and educational programmes for Afghan children, she is a sign of the progress that has been made.

Half of the organisation’s pupils are marginalised street children and nearly 40 per cent are girls.

“People call me a war photographer and I hate that,” McHugh says.

“One of my favourite photographs was taken of skateboarders on Bibi Maru hill.

"Even in the current state of decline that is Afghanistan, as things get worse and worse, you find this ray of hope.”

In most other places, however, he sees a country defaced by cracks and falling powerlessly into reverse.

Last year, he learned that NATO forces have already pulled out of some regions where hard-won victories had been achieved.

He says that Nuristan, where he got shot in 2007, is one such place that has been abandoned and quickly transformed into a lawless no-go zone overrun by Taliban fighters.

Meanwhile, in Kabul the middle class and the businesses community are preparing to flee. With many having bought homes abroad, the city’s housing market is in free-fall and last year alone £2.9billion was legally exported from Kabul airport.

“But what is really depressing for me is that although I will continue to work out there as long as it is safe, an awful lot of British and American reporters are leaving," McHugh says.

"And once everyone is out, nobody is going to give a damn. Afghanistan will be off the news agenda, especially if North Africa turns into the new front of the War on Terror."

Falling back into the sofa, seemingly defeated by his own premonition of the next chapter of the story he has expended so much of his life telling, he adds: “I think that the US and Britain will want to forget about Afghanistan.

"There should be a great deal of shame about how much money has been spent, how many soldiers have been killed and how many civilian lives have been lost, when they are basically leaving behind something that, once it collapses, is no better than it used to be.

“A lot of people will want to avert their eyes from what happens.”