IRISH people are much more genetically diverse than previously thought, new research has shown.

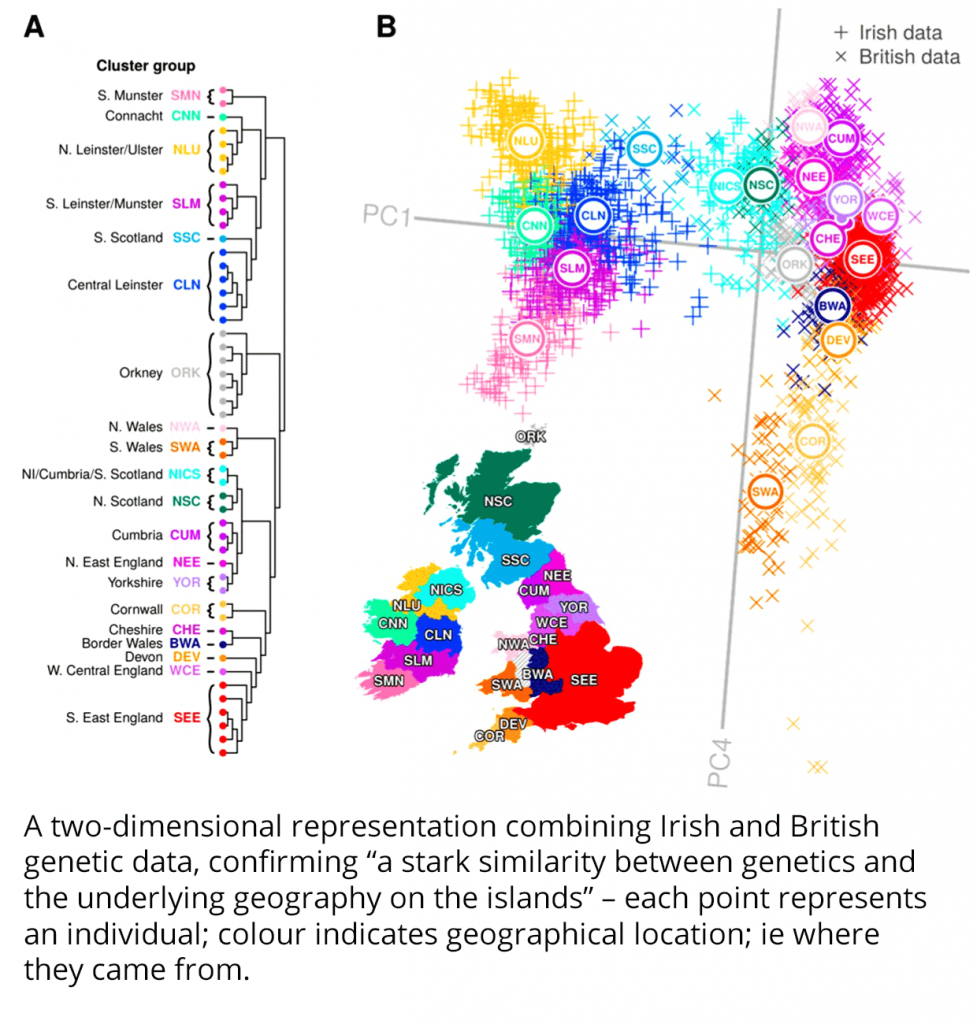

Sixty distinct ‘genetic clusters’ were identified in both Ireland and Britain by scientists at Trinity College Dublin (TCD).

Their findings show that the Irish have considerable Norman and Viking ancestry in their blood – just like the British.

It has long been assumed that most of the blood coursing through Irish veins is Celtic – but as evidenced by the map, the reality is far more complicated.

The study, published in the journal PLOS Genetics, could also shed fresh light on genetic diseases and lead to better treatments.

In both the Ireland and Britain, for example, the prevalence of multiple sclerosis increases the further north you go.

Compared with the rest of Europe, the Irish have higher rates of cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, and galactosemia – a serious metabolic disorder that prevents the breakdown of sugars.

The analysis was based on the DNA of 1,000 Irish individuals and 6,000 from Britain and mainland Europe – and confirms the vast extent of migration between the two islands.

The considerable genetic legacies of the Vikings, Normans and Ulster plantations has uncovered a previously hidden genetic landscape, shaped by invasions and migrations.

Previous studies had identified no clear genetic groups within the population of the Emerald Isle. But the researchers have now identified 23 distinct genetic clusters throughout Ireland.

These are most distinct in the west of Ireland, but less pronounced in the east – where historic migrations have diminished genetic variation.

When the researchers took into account genetic contributions from people with UK ancestry, an obvious trend arose – showing less and less British DNA further west.

They also detected genes from mainland Europe and found the timeframes of the historical migrations of the Norse-Vikings and the Anglo-Normans to Ireland to be consistent with their findings.

“Genes mirror geography in Britain and Ireland,” said Professor Russell McLaughlin, co-author of the research.

“Genetic data alone can virtually redraw a map of Britain and Ireland. It is interesting to note the exceptions to this rule.

“For example, some Scottish and Northern Irish people swap places, reflecting long-standing exchange of peoples between the two regions.

“Also, people from Orkney and Wales have retained some sort of ancient genetic identity that sets them apart from the expected patterns.”

Lead author Ross Byrne, a PhD student at TCD’s Smurfit Institute of Genetics, explained that previous research using Y-chromosome DNA showed “little remaining signature of the Viking Ages in the DNA of Irish people”.

However, he added: “These older studies used less than 1% of the available genetic information and focused only on signals that could be read through the paternal line, which may not tell the entire story,” he added.

“There is indeed a small but noticeable legacy of Viking influence in Ireland.”