MONDAY marked the 100th anniversary of the momentous first shots being fired in the Irish War of Independence on January 21, 1919.

Events were held throughout Ireland this week to mark the historic date, which also saw the first meeting of the Republic’s new revolutionary parliament; Dáil Éireann.

London-based author and historian Kevin Haddick Flynn takes a look below at the contentious event which sparked Ireland’s historic break for freedom…

The spark

A century ago on a quiet Tipperary roadway a revolt against the British Empire was started by a small band of armed men from townlands and villages in the vicinity of Tipperary Town.

Two policemen were shot dead by Irish Volunteers as they attempted to hijack explosives and arms for use against the forces of the British Crown.

The Soloheadbeg ambush, on January 21, 1919, shook British rule in Ireland and sparked a controversy which can be heard to this day: were the Volunteers, in the circumstances, justified in taking life?

Prior authorisation of the action was not sought or received from Volunteer headquarters in Dublin, and Dáil Éireann had not yet approved the opening of hostilities against the Crown forces.

The background to the ambush throws some light on the momentous decision to attack.

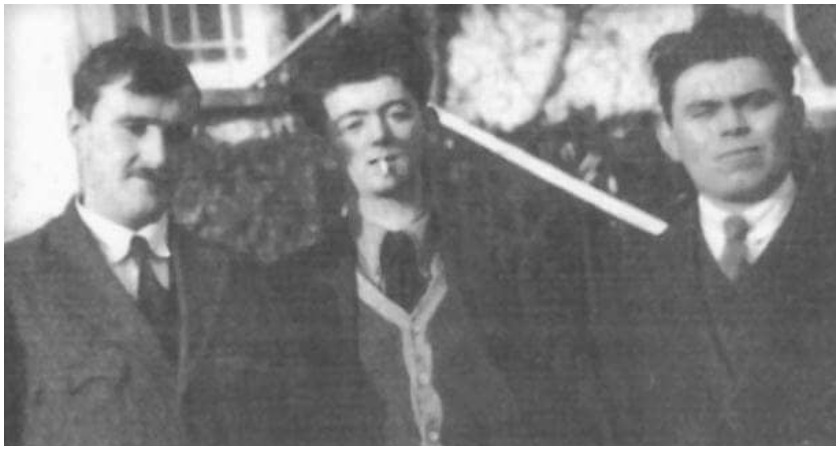

Sometime before Christmas 1918, Seamus Robinson, Sean Treacy, Dan Breen and other members of the Third Tipperary Brigade received intelligence reports that a large quantity of gelignite was due to be delivered to Tipperary Town for quarry blasting.

They became determined to seize the gelignite for use in the hostilities they intended to open shortly against the enemy.

The plan

A faction within the Volunteers had become restless in the years following 1916's Easter Rising. They felt the organisation was becoming too closely associated with Sinn Féin, a party whose republican credentials, at this time, were unclear — they were still a coalition of dual-monarchists, republicans and home rulers.

The Volunteers were frustrated, and believed that the movement would go to seed unless military action began. They decided to set the pace in Tipperary, and plans for the seizure were drawn up.

They allowed for various military contingencies. One plan was based on the possibility that the guard would be a small one, and that the RIC men could be overpowered without firing a shot.

Tadg Crowe, one of the Volunteers, had been earmarked to march the RIC men down the road after the seizure and to keep them covered while his colleagues escaped; then to withdraw himself.

At another stage of the planning, gags and ropes were hidden in the quarry, so that the policemen could be tied up and left to cool off in a nearby field.

The big question was: how many policemen would accompany the load? On this they could only speculate.

The attack

On the fatal day, one of the Volunteers, Paddy Dwyer, was posted as a watch-out in Tipperary Town. He saw the explosives being loaded on a cart outside the military barracks and noted the size of the escort: only two policemen and two council workmen.

He cycled ahead and informed the commanders Robinson and Tracey that the cart was on its way. The ambushers took up their positions behind a hedge and waited.

The horse was led by one of the workmen, and the two policemen, Constables MacDonnell and O'Connell, walked behind with their heavy rifles slung on their shoulders.

The affray when it happened lasted a matter of minutes. The cart came abreast of the gate and a challenge was shouted.

The RIC men were taken aback and initially thought it a practical joke. But on seeing the masked men they moved to unsling their rifles.

Constable O'Connell stooped for cover behind the cart; Constable MacDonnell went to do likewise but fumbled with his weapon. Sean Treacy opened fire with his automatic rifle and Robinson and Breen fired their revolvers.

The two policemen lay dead on the roadway. The two workmen looked on, stupefied.

The question is — did the policemen attempt to fire their rifles? The fact is neither of their weapons were discharged. Even if their rifles were in fact levelled on the ambushers (and there is no reason to disbelieve they were) the policemen were still at a disadvantage with the element of surprise against them.

There is little doubt that Treacy fired the first shot. Perhaps he believed that if he did not shoot quickly, he would have been shot himself. He was a humane man and it would have been out of character for him to have killed in cold blood.

One theory is that he may have mistaken the movements of the policemen. His eyesight was acknowledged to be poor and rain was falling heavily. Against this, the road at the point of the ambush was only seventeen feet wide — the policemen would have been less than a dozen feet away.

More likely a possibility is that that Constable MacDonnell's fumblings with his rifle were misconstrued.

Or it is possible that Treacy himself panicked?

The aftermath

Endless scenarios can be speculated upon. At the time, the other members of the unit — Tadgh Crowe, Paddy Dwyer and Sean Hogan — were unanimous that Treacy, Breen and Robinson only fired when they found they were in danger themselves. They had to make a split second decision.

More widely, shock and outrage followed the killings. The local newspaper The Nationalist described the ambush as "a very deplorable affair", a common view on both sides of the Irish Sea.

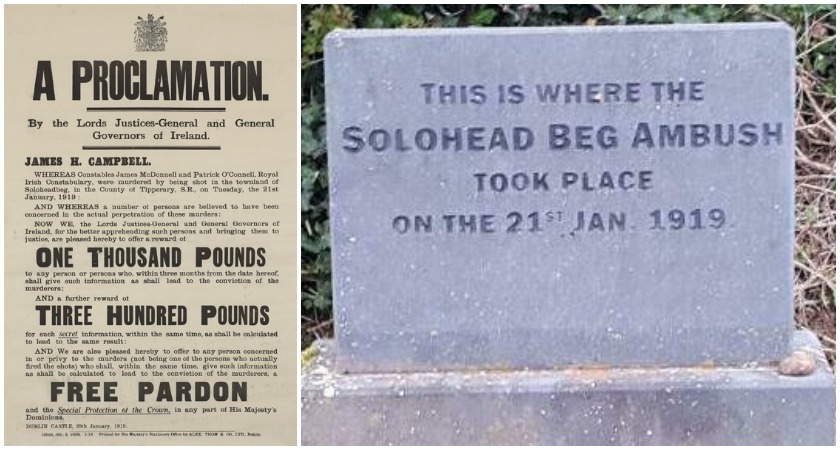

The forces of the Crown were quick to move. Tipperary was designated a "special military area" and a tight security clampdown put into operation. Dozens of people were taken in for questioning. All local fairs and markets were cancelled.

A reward of £1,000 was placed on Dan Breen's head, raised to £10,000 three months later.

At the inquest the coroner described the Soloheadbeg tragedy as the saddest that had ever occurred in Tipperary.

The medical evidence was that Constable MacDonnell was shot in the left side of the head and through the left arm, and that his death was instantaneous: Constable O'Connell was shot on his left side, and from the track of the bullet he must have been in a stooping position. He appeared to have been shot from behind.

The workmen Flynn and Godfrey were unable to say whether the policemen offered resistance. Their evidence was hopelessly confused. Flynn collapsed in the witness box and had to be removed to hospital. A nervous breakdown was suspected.

Both policemen were widely acknowledged to have been quiet, inoffensive men, well-liked in Tipperary Town.

Constable MacDonnell, from Co. Mayo, was a widower with a large family. He had been stationed in Tipperary for thirty years.

Constable O'Connell was a native of Coachford, Co. Cork, and was known to be a caring type. Neither man had strong political views. Both were unquestionably in the RIC for bread and butter reasons.

Nonetheless they were members of a widely unpopular, repressive armed force. The RIC had repeatedly enforced harsh, unpopular and often violent policies for generations.

The two policemen were vulnerable on two counts: because they were the handiest source of arms and ammunition which the Volunteers desperately needed; and, crucially, they were responsible for ensuring that the King's writ ran in a land which was now largely republican.

The lingering question

Shot dead: Constables James McDonnell, from Belmullet, Co. Mayo and Patrick O'Connell, from Coachford, Co. Cork

Shot dead: Constables James McDonnell, from Belmullet, Co. Mayo and Patrick O'Connell, from Coachford, Co. CorkWhether the Third Tipperary Brigade acted without authority is seen by some to be of little importance, for Dáil Éireann never formally declared the opening of hostilities in the War of Independence.

It did not accept responsibility for the actions of the IRA/Volunteers until April 1921.

The War of Independence developed from actions like that of Soloheadbeg and the British response to them.

Ten days after Soloheadbeg the official organ of the Volunteers, An tOglach proclaimed that every Volunteer was entitled to use "all legitimate methods of warfare against the forces of the English usurper, and to slay them if necessary to overcome their resistance".

Soloheadbeg was the one episode in the careers of Breen and Tracey around which speculation and controversy raged. In subsequent attacks on RIC barracks the record shows that they conformed to an operational code.

But is there still a lingering doubt about Soloheadbeg? Did they or did they not carry out a murderous ambush on two unsuspecting policemen from the shelter of a ditch?

Today Tracey and Breen lie beyond the controversy, safe in the immortality and affection given to Irish patriots. And history – truly the hard-hearted Muse – has forgotten the policemen.