AS The Irish Post's staff photographers and with almost 80 years between them photographing London's Irish community, father and son duo Mel and Malcolm McNally have enjoyed rare and unprecedented access to some of the biggest historic, political and cultural moments of the Irish in Britain. As the paper's 45th anniversary year comes to an end, we take a look behind the lens with Mel and Mal...

The early years in Ireland...

Mel: I served my time in my home county of Longford from about 1948 with the Midlands Photographic Company for five years. We covered the Midlands area in Ireland. At that time there were no staff photographers at the regional papers at the likes of the Westmeath Independent and the Longford Leader.

We did the agricultural shows and general sporting and news events. We used to do the dances then as well. You’d give out tickets to the couples whose pictures you took and then a local shop in the town would display them and you could go in and buy them or order them if you wanted to.

I had fairly good cameras for the time. I had a Rolleiflex and a Rolliechord and I had a German-made Leica, which was one of the most expensive at the time and that was fantastic. I had always wanted to be a photographer really – when I was about 12 there was a chap called Joe Shakespeare who used to come and do the agricultural shows.

They had plate cameras in those days so I used to help him carry his bags when he’d get off the train or the bus. I was his bag man I suppose!

Coming to Britain...

Mel: I came over to Britain then in the early 50’s with some of my friends because there wasn’t much photography work in Ireland at the time – it was hit and miss.

The Irish Post was only starting then – the founder Brendan Mac Lua worked for the Evening Press newspaper in Ireland before he started the paper and there was also a Sunday Review picture magazine in Ireland at the time. And I had been taking pictures for both.

So when I came over here I met with Brendan again – he needed a photographer - and we had a bit of lunch and from there we went to the Irish clubs in London, the Garryowen in Hammersmith and all the others.

Getting to know all the people involved with those was very important. They were our readers. The Irish people, even to this day, have what we call the mammy syndrome. It didn’t matter who the photographs were for or where they were going but if it could be published in the local papers at home for mammy to see then that was great.

But The Post, for the first time, took the glamour off those papers at home and being a London-based paper that became even more attractive to people. At that time we had a circulation of 60,000-70,000.

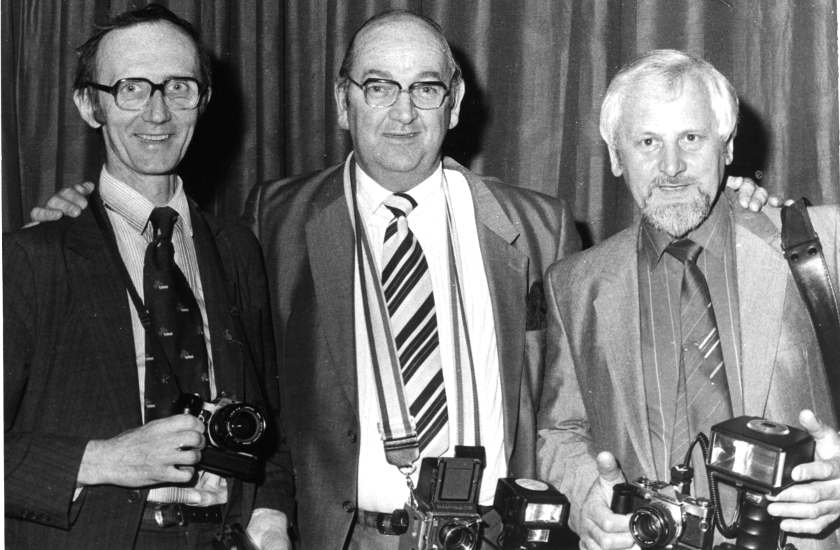

Federation of Irish Societies annual congress in Portsmouth 1981 - Malcolm's first Irish Post assignment

Federation of Irish Societies annual congress in Portsmouth 1981 - Malcolm's first Irish Post assignmentLondon in the 70s...

Mel: The Post was a Godsend to everyone in the 1970’s - business, commerce, construction…before that there was nothing. You got a local paper from home and you passed that on at church and then swapped it with somebody else.

But all those were nationalised papers so you only had Ireland’s interpretation not the facts as they were for the Irish in Britain.

Around that time the Federation of Irish Societies and the County Associations had also started setting up and they were big dance events at the time. There’s only a few surviving ones now like Longford and Kerry but initially every county had one. And they had a big crowd.

The Associations and the Church community groups have almost disappeared now. We used to get newsletters every week about who’s getting married, who’s dead – but they’ve been done away with now and you get a monthly one, which is no good.

Attitudes are not the same. For me it’ll never be what it was – the halls are gone, the showbands are gone, the atmosphere is gone.

When the bands used to be in tour – Mick Delahunty and the likes - they did gigs all around the country. Irish Ferries did a lot at the time by putting on people like Johnny McEvoy and they were great.

I remember at the time how the nurses used to get in free before nine-o’clock to all the dance halls. People weren’t on big pay so it was a nice gesture.

But over the years it didn’t matter who you were taking pictures of – the ordinary nurses and builders, politicians or celebrities.

Big Tom performing on the last night of the Galtymore in London in 2008

Big Tom performing on the last night of the Galtymore in London in 2008I remember I took some pictures of Pierce Brosnan once when he was in the West End with a new film. He was as accessible as any of the rest of them.

The celebrities I’ve photographed have mostly been very accommodating because they were all Irish. Spike Milligan was in the Irish Embassy in London one night, and you know what people can be like when they’re celebrities, we want this we want that.

But he came over and said I’ll be here for just half an hour so let me know if you want any particular shot and we’ll sort it out now.

The Birmingham Six...

Malcolm: It’s been a mixed bag over the years – different editors have you doing different things. Some have you doing lots of news stuff, when Donal Mooney was editor in the 90’s he was quite political and so would have you going to Westminster meetings and covering the Irish in Britain representation group.

We’d cover all the party political things. And they’re always the social events and stock things that need to be done.

But the highlights had to be the campaign stories – like the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four‘s fight for justice. We were involved in that for years leading up to them getting out and then particularly during the time of the first appeal in the late 80’s and again in the early 90’s.

We covered all the days in court and the comings and goings. You really got to know all the families who were campaigning – I think it was Billy Powell’s daughter that ran the family campaign so we were always involved in that.

"I remember it was a world news event the day the Birmingham Six got out – on that day I felt quite proud of the paper’s involvement, I’d go as far as saying it was one of our finest hours."

On that particular day there was thousands of cameras and trucks that were following them after they were released. We got a tip-off as to where they were going and when we got there they only let three of us in - me, dad, and Paul Gribben, the journalist.

The BBC all the others, they wouldn’t let them in but to The Irish Post they said in you come and have a beer. We ended up in a kitchen taking family pictures and just chatting to them. Looking back now it all seems a bit surreal.

Mel: I also remember the time of the Birmingham six just prior to their release. Around the square mile of the Old Bailey the pubs and restaurants had been told not to serve any of the IRA or their supporters so Fr Bobby Gilmore, one of the priests who played a big part in their struggle for justice, told me that there was a convent nearby that they were all going up to after they were released.

So the three of us jumped in a cab – the journalist Paul Gribben, Malcolm and I. There was a reception and a good crowd and we were the only press people there so we had a good scoop with that story around the world. You could work with your own because they were your own, you know – there was no class distinction.

But that said I’ve been here 50 years now and the English people themselves, 99 per cent of them have no problem with me being Irish or Catholic. You do your job and they do theirs, the police were the same.

I remember prior to the Birmingham six release, one of the days that court was on instead of going down to the Old Bailey I went down the road leading off the back of it.

I was there when the police van pulled in and the escort van pulled in and I said to myself I’m a winner, I can get a picture here. So I took a few pictures of the six getting out of the black van and policemen getting off their bikes.

But while I was sitting outside in the car a policeman came up and asked who I was with. I told him The Irish Post.

He asked me not to publish the pictures or he’d have to take the camera and film from me there and then. So I said ok. It didn’t really matter in that instance anyway - we had other shots.

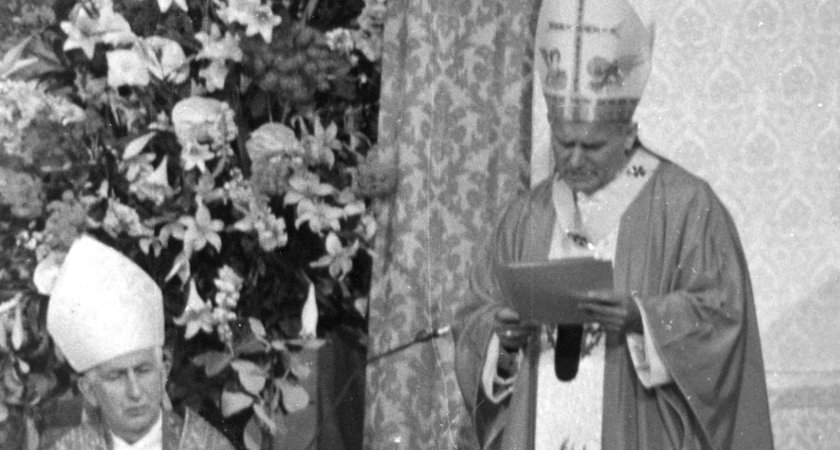

Photographing the Pope...

Mel: I’ve had just one hairy moment in all my time as a photographer and that was during the Pope’s visit to Knock. I covered the visit both in Britain at Wembley Stadium and in Ireland in 1979. There he visited Clonmacnoise in Westmeath, he was in Drogheda, he was in the Phoenix Park in Dublin. But it was in Knock that I saw him.

During that visit there was a couple of photo pools for the photographers to take pictures from. I was in one pool with about 12 other guys when next thing you know this one guy has run through security towards the Pope.

Straightaway you had plain clothes and special branch security all over him. This fella got about 30-40 metres to the Pope before they managed to close in on the situation.

Once they were on top of him he threw his passport into the crowd so that people would know who he was. I had been taking pictures up to this point but broke outside the press area to pick it up.

There was a fella next to me from the Mirror I think and then the special branch guy came over saying he wanted the cameras.

I gave him the wrong one of course - I had three cameras – and kept the one with the pictures in. But unfortunately another fella then piped up to tell him that what I’d handed over wasn’t the camera I had been using – the guy then grabbed all three cameras and took the film out of it.

Albert Reynolds was Ireland’s Taoiseach at the time and was also a friend of mine from back in my Longford days, so I said to the guy I’ll be seeing about this, getting my cameras back.

First I went down to the police station, where the sergeant simply said to fill in a form, which was no good to me.

So I went home and phoned Albert to see if he could help. He got back to me awhile later and he said: “I’ll tell you what Mac, that was people always called me, I heard about that incident and you were lucky you weren’t shot.”

He told me that there had been snippers on the roof of the church and when I’d broken the pool with the other photographer anyone of us was liable to have been shot!

He phoned me again a couple of days later to say that he didn’t know who the guys were that had my film and cameras, it was that wrapped up.

Malcolm: The Pope is probably the most famous person I’ve ever photographed and that was fairly early one when I was still at college. Another Irish Post photographer Brendan Farrell was supposed to be going to Rome with the crowd from Coventry but he got sick and I was asked to go instead.

The Pope had been in Coventry a year or so before that event and the Irish people from Coventry went back to have an audience with him.

So I pushed a couple of nuns out of the way and got a picture of him with the chalice being handed over! That was quite a big job.

"It’s a terrific profession really from top to bottom. Everything is a potential news item."

Malcolm: I started working for The Irish Post in 1981 because I’d just been accepted on this photography course.

Dad used to do it a good few years before and even though he’d been in London since the 50’s he wasn’t great at driving around so I’d help out with that.

If he’d have a job on in Camden and I’d tell him the best way to go.

Photography wasn’t a definite choice of profession for me though.

When I was in my last year at school the careers teacher asked me if I knew what I wanted to do. I said no.

He then asked what my dad did and when I said photographer he asked if I’d thought about doing a photography course and I thought yes, I could give that a go!

So I applied to Ware College in Hertfordshire and got accepted.

My first job was one where dad was heading down to Portsmouth for a Federation of Irish Societies annual congress and again I sort of tagged along. He gave me his old camera stuff and said why don’t you take a few pictures?

He took a few that day but the rest of congress I took. Those were the first pictures that I had published.

Then that September I went to college and started supplying The Post with a few more pictures to earn some money. The paper’s editor Brendan Mac Lua would ring up and say ‘oh, could you cover a Feis’ or a show or whatever.

It was a little bit strange at first, apart form driving dad to the odd thing the whole London Irish scene wasn’t really my kind of thing apart from the local Irish community out where I lived.

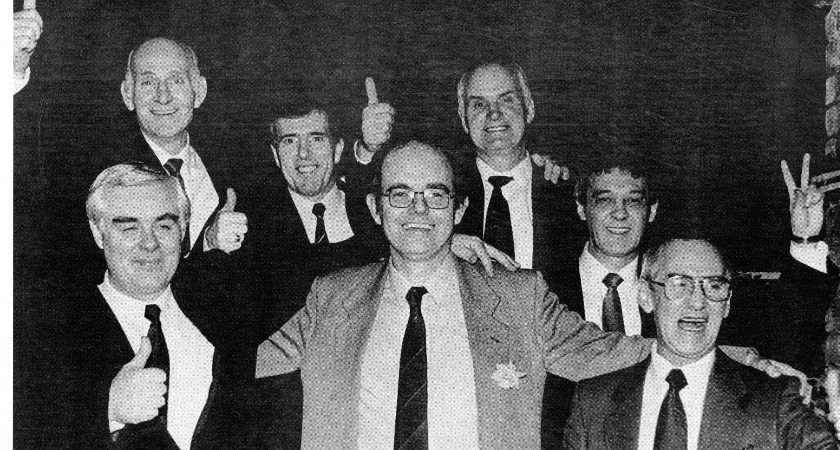

A Longford Association London presentation to Mel McNally

A Longford Association London presentation to Mel McNallyGoing to London to all the dinner dances was all fairly new to me. I mean I knew about Irish dancing – I did a bit myself but don’t tell anyone that! - but that was it.

At that stage I was only part time and doing other part time jobs to keep up. Then about 1986 Brendan offered me a retainer - I’ve always worked freelance - and he said how about if we give you a retainer each week whether the pictures are published or not.

I did a few jobs for The Irish Post and a few for myself. That was quite appealing, it was the 80’s and there wasn’t that many jobs around at the time.

I started getting more and more into what I was doing at the paper.

Westlife and Irish Ambassador Daithi O'Ceallaigh and former Irish Post journalist Michael Coughlan (far right) at Irish Post Awards

Westlife and Irish Ambassador Daithi O'Ceallaigh and former Irish Post journalist Michael Coughlan (far right) at Irish Post AwardsCelebrity moments...

Malcolm: The Irish Post opens doors. And it always helps, if you’re meeting politicians or anybody really. You say you’re a photographer and they hesitate but when you add ‘From The Irish Post’ you get a ‘Oh, that’s ok then, that’s fine.”

I think the paper had always been highly regarded and all the politicians all seem to know the paper. Even some of the Loyalist politicians when they’re over say yes to a picture, which always surprises me.

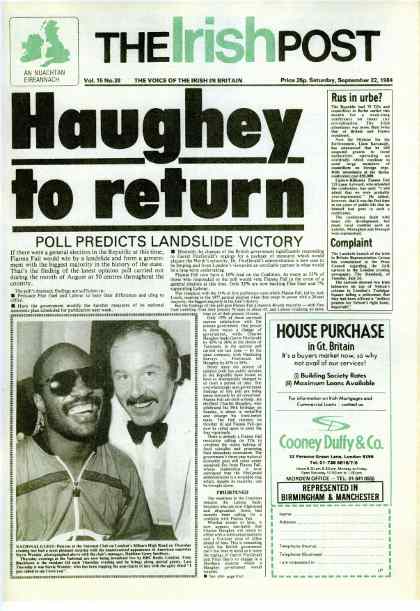

Stevie Wonder and Gerry Smithers from the National Ballroom in Kilburn on the cover of a 1984 issue of The Irish Post

Stevie Wonder and Gerry Smithers from the National Ballroom in Kilburn on the cover of a 1984 issue of The Irish PostThen there was years ago when I took pictures of Stevie Wonder at the National – which had a Dublin-born owner.

Having a black man on the cover of The Irish Post in 1984 was not the norm.

I’d left college at that stage and had a couple of college buddies with me.

The National Club in Kilburn was somewhere that everyone used to go to – the Wolfe Tones used to play there to two-three thousands people.

But the owners were quite forward-thinking and they used to have something called the London soul night out – but even that would be half full of Irish people.

I’m a big soul fan so for me to meet Stevie Wonder or someone like Marvin Gaye is huge! I had a little chat with him and thought blimey that’s pretty good.

But then there’re also so many Irish Post Awards people – so meeting someone like Noel Gallagher was pretty good. And he was really nice. He was there with his mum Peggy.

We used to invite the outside press to cover the pre-drinks reception before the ceremony and I remember there was lots of paparazzi, not so much photographers, there that year.

No-one was saying can you look this way or that it was just jump in and take the picture. So that did p**s people off.

I just left him alone, knowing he was going to be there for awhile. I could see his mum was impressed that Lonnie Donegan – the old king of skiffle – was there.

So I went up to him later on when it had all calmed down – he had his shades on and was all rock and roll - and asked ‘Would you mind if I got a picture of your mum with Lonnie Donegan?’.

He was, ‘Oh she’d love that man.’ He then asked if he could have one as well so I was said sure, jump in!

From that he took the shades off and relaxed a bit. Sometimes you just have to let people relax and you’ll get the picture.

Dad was well-known in London when I started taking pictures and so really I’ve become young McNally, the lad – I think I always will be to some people.

It’s a very close-knit community. And while there are some people who don’t know about The Post the people who do read the paper do get involved in the Irish music to take an interest in charitable things or the GAA.

Then as they get slightly older they want to get their kids into music and dance and things like that.

Some of the County Associations are still thriving, you go to a Mayo do and there’re loads of young people at them – they’re thriving.

Whereas you go to another county dinner dance that’s being organised by the same person for the last 50 years and there’s no-one at them.

I think if you can get a couple of enthusiastic younger people they’ll come on for a year or two but will get fed-up with it if the older people won’t let go of the reins.

It’s not right to say we’ll have young people on board but it’s still our organisation and what we say goes. There has to be a bit of give and take.

"I’ve always got the pic – there’s ways and means around everything"

Over the years there's never really been any hairy moments. I’ve always got the pic – there’s ways and means around everything!

Stylewise with my pictures it all depends. If you’re working on an unusual news story you try do something a bit quirkier for that kind of picture.

In general I like to stick on a biggish lens and just capture people as they are rather than line them up. If you can get a few of those then that’s great.

It’s only in the last 10 years that I’ve started to work in digital – I was quite late to it. It was black and white form the very early days to the mid-nineties and the it went to colour, which was a Godsend.

Queen and Prince Edward with fromer Irish President Mary Robinson

Queen and Prince Edward with fromer Irish President Mary RobinsonUntil then I had to go to the darkroom. Once I’d moved to colour the process was much easier. It makes things easier, cost was lower as well.

In the early 2000’s I persuaded the then editor Frank Murphy that it would be a good move to invest in some good digital equipment as the cost would be no where near what it was for developing photographs.

It was at the point where I was getting really busy and expenses added up. On the digital side of things there was no expenses really in the long-run.

You can also take more shots and you don’t have to worry about coming to the end of a film.

You can just shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot and be more relaxed and be more creative and try different shots – things like what if I didn’t use the flash here or play around with the background light.

But basically a good rule of thumb is not to stray from what you see in the viewfinder because that’s what you’ll get in the picture – they teach you that from day one in college!