THE LONELY Irish pensioner who took out a newspaper advert to find company this Christmas served leading world figures during his career as a butler, including former US President Ronald Reagan.

James Gray’s story has taken the world by storm this week.

Thousands were left heartbroken after hearing of his plight and how he had spent the festive season in solitude for the last decade.

But the 85-year-old will be opening his first gifts in years next week thanks to those who have been touched by his story.

The Irish Post has received more than 1,000 Christmas cards from readers. They have come from as far away as Chile, the US, Australia and Japan.

London-based James has also been inundated with cards from his native Ireland, where his story has become national news.

In an interview with The Irish Post, James said it was “hard to take in” the global support he has received.

James Gray will not be alone this Christmas

James Gray will not be alone this ChristmasThe retired butler also spoke of how he missed his working days. British Prime Ministers and US Presidents were among those he served during his career.

In one of the photographs hanging in the hallway of his home, James is pictured with then-President Ronald Reagan and the other staff who served him during a visit to Britain.

“All I remember is pouring champagne for the huge crowd that turned up for dinner,” he said.

“There were about 100 people there on the night Mr Reagan was there.”

Shortly after leaving his job at the US Embassy’s Winfield House, in Regent’s Park, James worked for Hambros Bank in London’s elite Belgravia district.

There, he served the likes of Prime Minister John Major and British royal Princess Anne.

“John Major used to come there because the businessmen who used to give cheques to the Conservative Party would come there and meet him,” he recalled.

“Mr Major shook my hand when he came in a couple of times and I always meant to say ‘Your son has the same name as me’. But I didn’t get the chance.”

A painting of the residence where James served as a butler

A painting of the residence where James served as a butlerLike the former Tory leader, James said, Princess Anne regularly visited the company to collect charity donations from wealthy businessmen.

“When they gave a dinner party for the princess I was behind a chair and she never even looked at me when she came into the dining room,” he added.

James life as a butler was a world away from his upbringing in Ireland. He had fled Ireland in his late teens after enduring a difficult childhood.

He was born in a workhouse in Midleton, Co. Cork, because his mother was banished from nearby Carrigtwohill for “bringing shame on the town” by getting pregnant.

A five-year-old James was then educated by nuns at a local convent before being turned over to the Christian Brothers at one of Ireland’s notorious industrial schools.

The institutions were shamed in the 2009 Murphy Report for endemic sexual abuse of children.

Painting a grim picture of his schooldays, James recalled the “bully” priest who kept watch over him. And while he did not witness any physical or sexual abuse, he said he had no good memories of the institution.

“All day you were in a yard with a great big wall all the way around it – you were stuck,” he explained.

“And I know that in one corner there was a lavatory, but there were rats running up and down the place. It was not even a room, it was off the yard.”

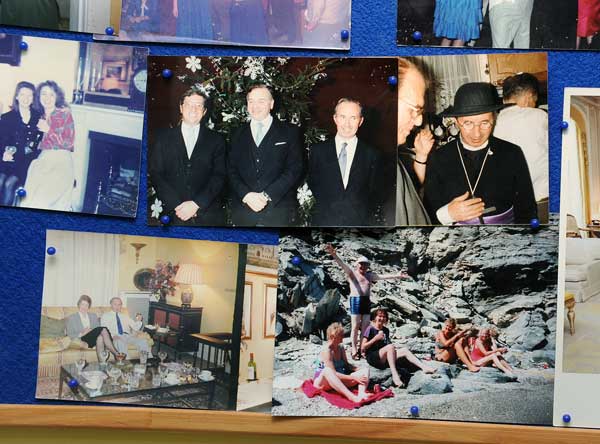

Some photos from James' life

Some photos from James' lifeJames then worked on three farms from the age of 14. But he ran away from each after traumatising experiences.

The first time he fled it was because a cow kicked him while he was milking it. The second time he left after having to sleep on a “bed of fleas” for months.

Turning his back on farm work for good, James later left a farm in Co. Tipperary after its owner came up to his room in the middle of the night and attacked him in a drunken rage.

It was then that James got a taste of the work that would become his livelihood, working as a servant at a mansion in Crosshaven, Co. Cork.

Soon after, he found himself working for the Guinness family at Dublin’s Luttrellstown Castle – the site of the Beckhams’ wedding.

“It was very posh, the height of luxury,” James recalled.

“There were 20 staff and even the servants had their own classes.

“About 12 of us had to eat in our own room, while the others ate in a much nicer place.

“But I enjoyed working for the rich at a stately home much more than I enjoyed work on a farm.”

It was then that James boarded a boat and set out for England.

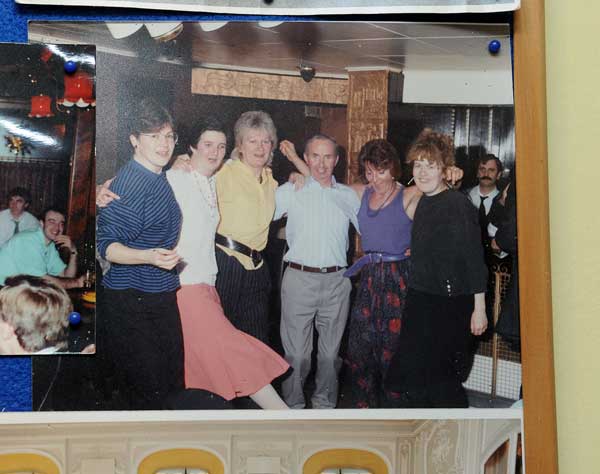

James with a group of female friends

James with a group of female friendsIn a long career that did not end until he was 73, he worked at big businesses and stately homes around Britain.

But although the photos pinned up in his home show that he had a busy social life, James said he struggled to make lasting friendships because work kept him moving from place to place.

“And I was working so much,” he added.

“You could be working all night, seven days a week.”

But James also blamed himself for ending up in his current lonely situation. His only regular contact with the outside world comes from the cleaner he pays to check up on him.

“I just couldn’t make friends,” he explained.

“I thought I might make a lot of friends when I emigrated, but I was not that sociable. I was very quiet, even though I went to parties and had parties.”

As he looks back on his life after a decade of isolation, one of the things James regrets most was his decision to marry a London woman in the 1970s.

“That was a mistake,” he lamented.

“I was 45 and I had known her about 12 months. I just got married for the sake of marriage.”

Niall O'Sullivan presents James with one of four boxes of cards and gifts from Irish Post readers

Niall O'Sullivan presents James with one of four boxes of cards and gifts from Irish Post readersIt ended after two years when James discovered she was having an affair.

His biggest regret came 20 years later, when he destroyed his last chance of finding companionship.

James had met a woman from the North of Ireland who was also in her 60s. But after living together for two months, it all ended over “nothing”.

“It was all because of a chicken dish,” he said.

“She cooked a chicken dish and then she went back there and said there was a piece missing. So I said ‘Well I didn’t take it’.

“But she was mad and I said ‘Oh well if you are like that then you had better leave’. And that was it. It was the biggest mistake I have ever made.”

Now, with no family or friends left, James lives with chronic loneliness.

But he remains stoical, saying he “won’t be beaten”.

“I have been alone all my life – it’s been like this ever since I was 14,” he explained.

“You see, you have to be strong if you are pushed out into the world on a farm when you are 14, with a suit of clothes, a prayer book and a set of rosary beads and about 30 shillings.

“You just have to get on with it and it makes you strong.”

But he admits that he wishes things were different.

“Behind it all, deep down it hurts to have no family and no relations,” James added.

“You go through life feeling like you are the only one in the world. Anybody coming into the world today at least has the State behind them, but I had nothing.

“I wish I had a family behind me.”