Recently a returned navvy, James Connolly, wrote to me from his home in Roscommon: “I have just been out for a walk, and heard the cuckoo for the first time this year. It lifted my heart, and put me in mind to write to you.”

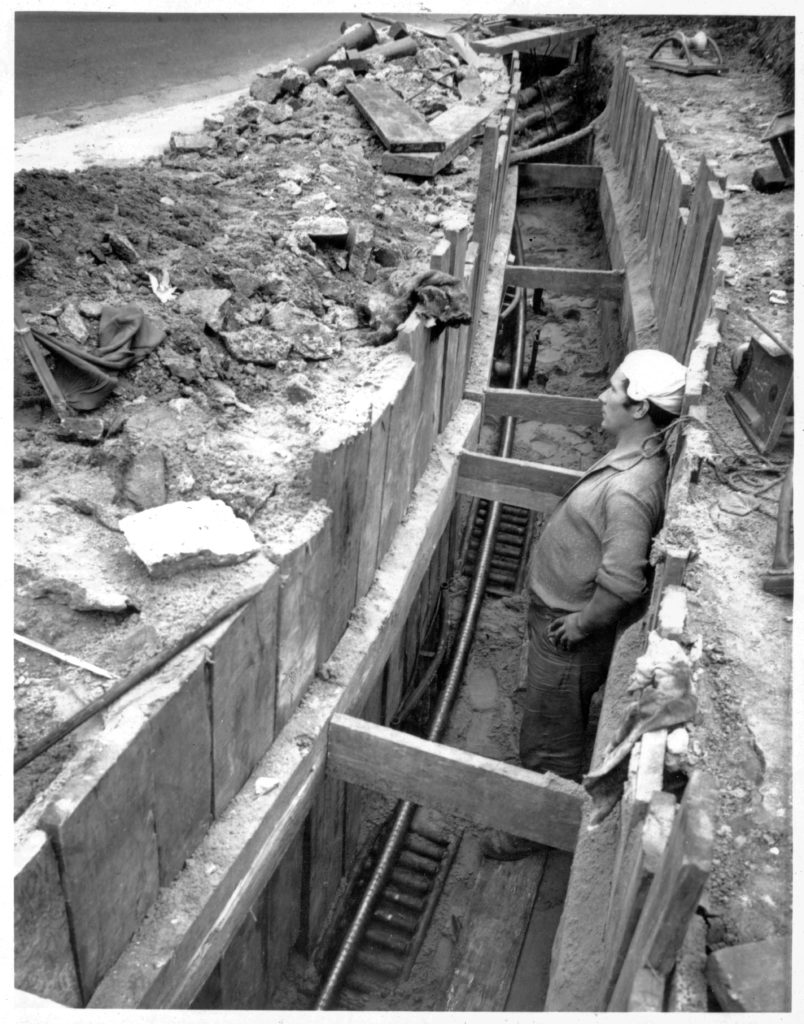

BUILDING BRITAIN A navvy contemplates his handiwork Photo supplied by Ultan Cowley

BUILDING BRITAIN A navvy contemplates his handiwork Photo supplied by Ultan CowleyHis is one of many letters from Irish emigrants who read my book and found there echoes of their own experience.

James told me about his years in England: “It was the early 70s when I went there, and I spent about twenty years around England and Wales, and Holland and Belgium.

“Recently I heard a programme on RTÉ about the literature of the Blasket Islanders, and the last sentence of An tOileanach was: ‘Ni raibh a leithead ann aris” and, as I often think about my travelling days, the same eulogy would apply to the people I knew then.

“‘The home nest could maintain but one, and the hard road for the others’ was the harsh rule which governed the lives of many families in rural Ireland in the first four decades after independence.”

Another writer, Jack Foley, summed it up: “Of my own family of nine, all except for two emigrated. One of my moist poignant memories is of my parents saying goodbye to my eldest brother, Tom, as he left to catch the bus at the end of our boreen. As the bus took off, and my brother waved up to the house, my mother ran down the road calling for him to come back. I was about six at the time, and I went to my mother and asked her why did she let him go, if she wanted him to stay? By the time the last child had left, I’m sure the pain had dulled.”

The girls had to be just as courageous as the men. Mary Morley was just fifteen when she too left. “My two eldest brothers came to England before me, at the ages of fifteen and sixteen. My mother was a widow, and an invalid, and I had to leave school early to look after her. I got six years’ education in all.

“When my mother died, in March 1945, I knew that my life in Ireland was over – we had no money, no home, and the outlook was very bleak. I answered an advertisement, in the Irish Independent, for a servant in a Jewish house in Manchester. I had never even been on a bus before but on the 14 th of November 1945 I took the bus, boat, and train to start my new life in Manchester. I did not know where it was going to lead me but it was a case of sink or swim.

“I wanted to prove to my brothers, and the people I had left behind, that I was not going to sink and, yes – I was going to swim! We were given a numbered label at the boat, to put on our lapels, and my number was seven. One thing I always kept in mind was that I had no thought of return to Ireland , so I always made sure that I had a pound in my purse, and a roof over my head.”

In British construction men made good but hard-earned money. At the end of the 1960s T.P. Ennis heard talk from older men about conditions as far back as the nineteen twenties. “My landlord in Shepherd’s Bush – a Conway from Mayo, told me about frying steak on the shovel, and pissing on blistered feet.

“At home on the farm, a particularly busy day was putting in or taking out a

crop, dropping the potatoes, gathering the hay and making the rick. Days of non-stop action - long, long, and dog-tired at the finish. I used to think how naive people were though, at home, to believe that they worked hard. They only did a few such days in an entire year. In England, on the buildings, every day was ‘a day of the rick.’”

In 1949 Myles Sullivan, from Enniscorthy, left school at sixteen but couldn’t find work: “My mother was a widow and we had no money at all. I got a part-time job with a local farmer, weeding. The ground was so hard that, after two days, my fingers were severely damaged and I gave up. I did seven 200 hundred yard drills and earned seven shillings. I picked blackberries that summer and sold them. I saved up £12.

“Everyone picked blackberries at that time because there was a big demand for them in England due to food rationing. Big demand also for wood pigeons, rabbits, and hares. We carried our buckets to town, and sold the blackberries to an agent – I think we got two shillings for each bucketful.

“Most people I know got to England then by picking blackberries. Some never came back, and most of the boys who picked with me are dead.”

Often the emigrants were little more than children, and it took courage to leave. It took courage to take on the challenge of living in a different culture and a different, essentially alien, society. As one woman remarked, “They taught us to hate England – and then they sent us over here!”

It took courage to remain. It also took courage to honour the onerous burdens of obligation – to succeed, to ‘keep the faith’, to send the money home, so unfairly imposed by those at home on those who had to leave.

Between 1939 and 1969 they remitted £2.3 billion in cheques and money

orders. How much more came home in hard cash – ‘the bundle of notes’ in the back pocket? Ireland’s education budget in 1960 was £16 million. Emigrants’ remittances that same year amounted to £15.5 million. Yet 82 percent of those emigrants, through no fault of their own, had left school at fourteen.

Fr. Owen Sweeney, chaplain to the Irish on McAlpine’s Spencer Steelworks site at Newport in South Wales, was moved to remark: “I came to appreciate the inestimable value of their contribution to human wellbeing. I came to regard them as the true nobility of society – humble, hard-working men who rarely complained about their lot.”

Few came back. As Theresa Gallagher, former director of Irish Counselling and Psychotherapy, once remarked: “We are finding deep wells of sadness in ordinary human lives.”

How many must there be then, who would willingly swap places with my friend James Connolly, so that they too might say, “I have just been out for a walk and heard the cuckoo, for the first time this year, and it lifted my heart.”?

Ultan Cowley

Ultan CowleyTo book Ultan's one-man show, Memories of the men who built Britain, contact him on +353 87 90060020 or email [email protected]