Following the popularity of the marriage referendum’s Home to Vote campaign and a recent OECD recommendation to the Irish Government to engage with its Diaspora on political representation, we ask if there is a renewed appetite for involvement in domestic affairs

HER twin is gay. So for Roscommon woman Caitriona Keigher, Ireland’s recent marriage referendum was a deeply personal issue.

“It was about brothers and sisters, parents and uncles,” she says. “I think it meant more to the ordinary man on the street.”

An Arts graduate, Keigher studied in France before arriving in London at the start of the summer.

The 23-year-old has been living abroad for four years.

“Roscommon was the only county in Ireland that voted no,” she says. “And the only reason for that is because we all left.”

For many younger Irish people living abroad the marriage referendum stirred a sense of civic duty, which spawned the hugely successful Home to Vote campaign on social media.

Engagement overseas was celebrated almost as much as the result.

Caitriona was unable to return to vote however. So too for Niall Culligan from Clare.

Both are stood outside the London Irish Centre in Camden. Both still feel the afterglow of the Yes vote and believe the Irish Diaspora should have the right to vote on domestic issues of similar significance.

“I don’t think it’s that drastic a measure,” says Culligan. “It’s taken for granted among citizens from other countries like America. Definitely, if I had the chance I’d avail of it.

“I don’t think I’d go back for a local election or a presidential election, there wouldn’t be much point.”

Typically, the appetite to connect with home affairs falls in and out of fashion with Britain’s Irish community.

Save for the staying power of a few campaigners the subject simmers but seldom boils.

Opponents argue that the Diaspora already has a talking shop of sorts in the Seanad. But neither Caitriona or Niall are aware of that fact and neither feels it’s of any value.

“I didn’t even know there were people in the Seanad representing us to be honest,” says Keigher.

Opponents to voting rights also point out that the political future of counties with high emigration would be determined by the whims of those overseas who may never return.

And what about overseas voters anyway? They don’t pay tax in Ireland.

“Ah but some of us do pay tax in Ireland,” says Barbara O’Donnell who has wandered along to the centre to attend a poetry event.

“Anyone who owns a property at home pays tax there. I own a home there and I pay tax. I also take my holidays there. I’ll grant you that’s small stuff but I do feel I contribute.”

The Bantry native has been living in London for almost 20 years.

She chimes with the graduate’s view that the Irish abroad deserve a vote on domestic issues of national importance.

But why does she feel this way after all this time? Has she not assimilated to life in Britain?

“I probably would be in the minority,” she sighs. “But you get a bit older and you think of going back in the long term and you feel like you want to remain engaged.

“I’d like to go home at some point so to be able to influence decisions there would be helpful for me.

“In terms of the referendum in the summer I think the reaction was so vigorous because it was the old versus the new and we’ve had that old dichotomy.”

For the Cork woman this sense of civic responsibility is not saved for Irish affairs. She felt compelled to vote in the recent British General Election too. Dubliner Ellen Travers has similar motivations.

“I believe in good citizenship and getting involved and more interested in local politics,” she says as she parks her bicycle. “I live in Islington where Jeremy Corbyn is an MP,” she smiles.

As for the non-payment of tax issue, she bats away the assertion. “But I have paid tax. And I will pay tax [in Ireland] again in the future.”

Travers wants the right to vote from Britain. But she is pragmatic and says returning to Ireland to ballot would be dependent on proposed changes in the constitution.

Or, similar to the marriage referendum, if she felt returning votes could make an impact.

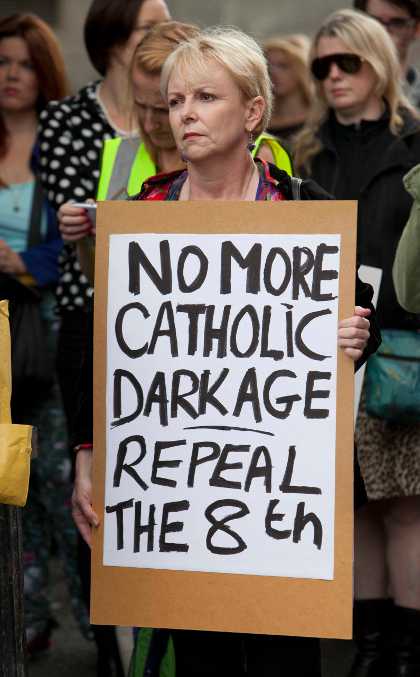

A public rally in Dublin in favour of repealing the 8th Amendment to the Irish Constitution. Photo Eamonn Farrell/RollingNews.ie

A public rally in Dublin in favour of repealing the 8th Amendment to the Irish Constitution. Photo Eamonn Farrell/RollingNews.ieShe says she wasn’t surprised that the newer, younger generation of emigrants chose not to abandon their political responsibilities.

And they might have, because of the economic situation that forced some to leave.

“It’s probably stirred up more activism and people feel a responsibility to shape their own future.” she says.

But voting rights abroad feels like a thing of changing temperature — where the degree of activism is determined by the issue and people’s connections with home.

The Home to Vote campaign and the marriage referendum clearly connected.

Both Barbara O’Donnell and Caitriona Keigher predict a similar embrace if a future referendum on abortion was to be held.

“That might get people to go home again,” says Keigher.

“They are the two main issues for young people these days.

"Gay marriage is one tick and then we’d feel Ireland is in the 21st century.”

Barbara O’Donnell adds: “The marriage referendum was a big step. The first true step in opening things up. The next thing now is to repeal the Eighth.

"We now need to get rid of the sh*te and repeal the eighth.”