AN OLD curse says: “May you be involved in a conflict when you know you’re in the right.”

The curse condemns you, quite simply, to be involved in a conflict that will last forever.

In the dying years of the 20th century that curse at long last began to lift in Ireland — even if one side knew it was in the right, it was prepared to see that other people were entitled to think they were right too; some compromise was needed.

A solution to the bitter struggle was finally found by a group of people that included, amongst others, John Hume, Bertie Ahern, Gerry Adams, John Major, Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, David Trimble — and Albert Reynolds

Perhaps Reynolds, Taoiseach at the outset of the peace process, doesn’t get as much credit as he should. His relationship with John Major — they became good friends — proved crucial in the early, tentative stages of negotiations.

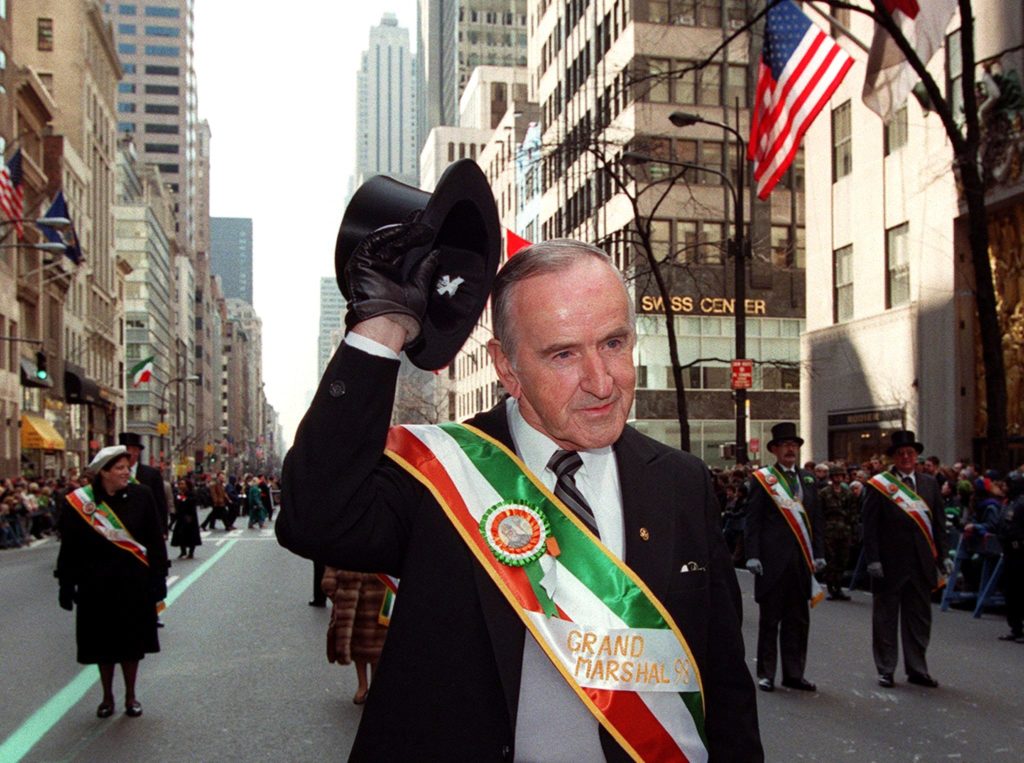

Former Irish Prime Minister Albert Reynolds, was the New York St Patrick's Day parade grand marshal in 1998

Former Irish Prime Minister Albert Reynolds, was the New York St Patrick's Day parade grand marshal in 1998According to a newly-published book Albert Reynolds: Risktaker for Peace by former TD Conor Lenihan, the Reynolds’ quest for peace was seen largely through the prism of business. The Troubles were hindering US investment in the Republic; the violence was imposing a high cost on the economy of the whole island.

Albert Reynolds was Taoiseach from February 1992 until December 1994. During that time he was a key player in the peace process, and a co-signatory with John Major to the 1993 Downing Street Declaration.

The Downing Street Agreement affirmed the right of the people in Northern Ireland to determine their future — a giant step forward.

Crucially, he also helped advise President Bill Clinton on the USA’s best strategy in helping end the imbroglio.

Out of the subsequent peace talks the Good Friday Agreement emerged, ushering in Ireland’s most peaceful century since the Vikings had first arrived around 800AD.

Reynolds had left the Dáil by the time the Good Friday Agreement was brokered, but his legacy remains.

From pet food to politics

Albert Reynolds: Risktaker for Peace by Conor Lenihan traces Reynolds’ life from his early days in Roscommon, growing up in an Ireland that survived on what was, essentially, a subsistence economy.

As the 1960s dawned Albert Reynolds, then a young man, discovered he was an astute business entrepreneur. After the ‘doom and gloom’ of the 1950s, Ireland’s economy was beginning to blossom.

Young people — those who hadn’t emigrated — wanted entertainment. Albert Reynolds was at hand; he promoted dances up and down the country, bought his own ballrooms. managed bands. Along with his elder brother Jim he built up a lucrative business. But the partnership ended in acrimony, with Albert eventually taking his brother to court in a legal dispute.

Then in a radical departure, Reynolds moved into pet food, and finally politics.

His showbusiness links proved invaluable in his political career. In one campaign when personalised posters were banned, Reynolds and his team got around this by getting the country singer Larry Cunningham to say they were his posters.

Reynolds was a self-made man, and his ability to do deals meant he quickly climbed the greasy pole of politics. He was TD for Longford-Westmeath, followed by Longford-Roscommon, finally becoming Taoiseach in1992. He immediately earned himself the nickname ‘The Longford Slasher’ by dispensing with eight of the old Haughey cabinet and firing nine of the twelve ministers of state.

Albert Reynolds: Risktaker for Peace traces his career through Dáil Éireann to becoming head of government, to his final disappointment in not being selected as the Fianna Fáil candidate for the Presidency of Ireland.

The final chapter traces Reynolds descent into Alzheimer’s and finally his death in 2014 at the age of 80. John Major, who visited him during his final years, said on his death: “He was a “A statesman. . . . Albert Reynolds was at the heart of the success of the Irish peace process. Without Albert, it may never have started — or might have stalled at an early stage — and Ireland, North and South, might still be enduring the violence that scarred daily lives for so long."

Albert Reynolds was successful in business before moving into politics

Albert Reynolds was successful in business before moving into politicsThe hijacking

While Minister for Transport, Reynolds was confronted by a crisis that no other Irish minister has ever had to face — a hijack.

In May 1981 Aer Lingus flight no. E164 departed from Dublin bound for London with 113 passengers on board. Before landing, a 55-year-old man, Mr. Laurence James Downey, rose from his seat, went to the toilet and doused himself in petrol. Presenting himself at the pilot's door with a cigarette lighter — in effect, a very low-tech suicide bomb — he proceeded to demand that the plane divert to France. It was Ireland’s first, and to date only, aircraft hijacking.

The plane eventually landed at the remote Le Touquet airport in northern France. The hijacker, a defrocked Trappist monk (he’d punched a superior), revealed what his demands were: to know the Third Secret of Fatima.

Taoiseach Charlie Haughey sent Reynolds to France to deal with it.

Reynolds patiently began negotiations with the hijacker, working alongside the security people.

Conor Lenihan describes the scene: “It was late at night and Reynolds, with the French, devised a plan to get an Irish newspaper to run a story the following day to the effect that the Pope had released the Secret as per the hijacker’s demand.

“Michael Hand, then a news editor with the Sunday Independent, and a friend of Reynolds from his music days, facilitated the ruse and Reynolds climbed the steps of the plane to talk with the hijacker. Simultaneously, a special forces crew climbed into the plane. Reynolds distracted the hijacker while they entered. The whole episode unfolded in full view of the world’s media and Reynolds travelled home something of a hero.”

The Presidential bid

In 1997 Reynolds threw his hat into the ring for the presidency of Ireland. He thought he had Taoiseach Bertie Ahern’s support and that the contest was a shoo-in. This proved not to be the case.

The other runners were Mary McAleese and Michael O’Kennedy, both barristers.

Mary McAleese emerged as a strong candidate giving impressive speeches, while the other two candidates were caught on the hop not realising speeches outlining their presidential agenda might be were needed.

Reynolds still thought he had Bertie Ahern’s support, but that was crumbling; McAleese seemed a better bet to most in the Fianna Fáil party. Ahern said he was still supporting Reynolds, but other TDs had to make up their own mind. . . .

Reynolds never forgave Ahern. He had suffered a bruising defeat and humiliation at the hands of McAleese, a complete outsider.

Albert Reynolds was finished with Leinster House. He did not stand as a candidate for the general election of 2002.

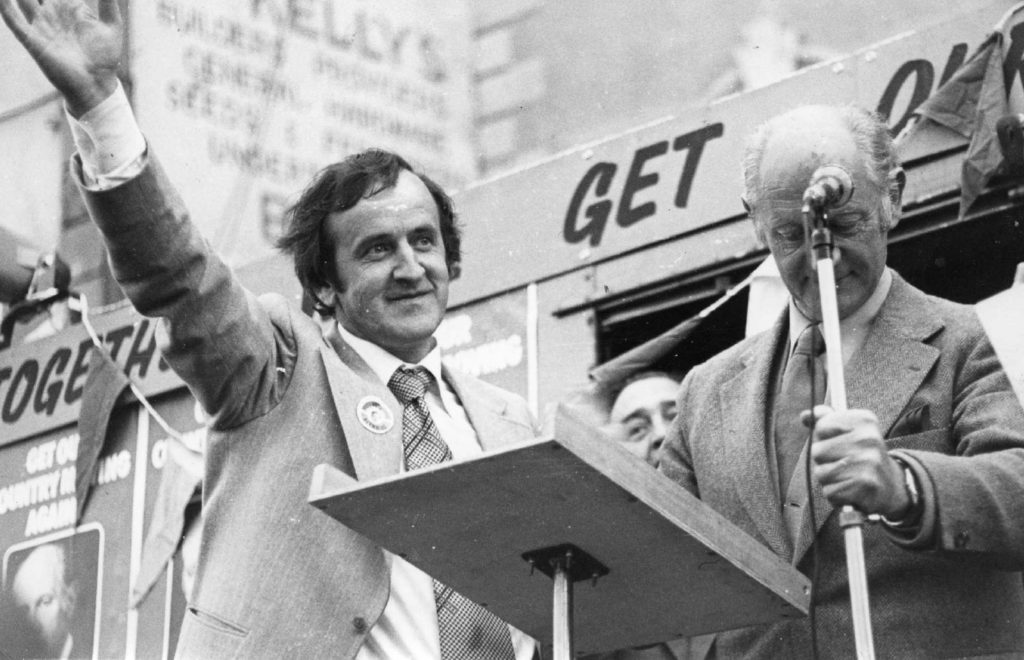

Prime Minister John Major and then Taoiseach Albert Reynolds address a press conference in London on December 15, 1994 prior to issuing a joint declaration to bring peace to Northern Ireland.

Prime Minister John Major and then Taoiseach Albert Reynolds address a press conference in London on December 15, 1994 prior to issuing a joint declaration to bring peace to Northern Ireland.The libel case

Reynolds was involved in a long-running libel action against The Sunday Times over an article published in 1994. It alleged he had deliberately and dishonestly misled the Dáil in connection with the Brendan Smyth affair — which had brought down Reynolds’ coalition government.

The article was headlined, 'Goodbye gombeen man – why a fib too far proved fatal for the political career of Ireland’s peacemaker and Mr Fixit.’

A High Court found in favour of Reynolds in 1996. But the jury recommended that no compensation be paid. The judge subsequently awarded contemptuous damages of one penny, leaving Reynolds with a massive legal bill estimated at £1million.

A subsequent court of appeal decision in 1998 ruled that Reynolds had not received a fair hearing.

“The second trial was a strange affair, all the more so because an eleven- person British jury was being asked to adjudicate on the intricacies of Irish politics in relation to an issue that even Irish jurors would have found it hard to understand,” writes Conor Lenihan.

The final round of the legal dispute came before the British House of Lords. The Sunday Times finally settled their dispute with Reynolds with a frank admission that he had not lied to the Dáil or his government colleagues.

Coffin of of former Taoiseach Albert Reynolds as it arrives at Shanganagh Cemetery for his burial on August, 25, 2014

Coffin of of former Taoiseach Albert Reynolds as it arrives at Shanganagh Cemetery for his burial on August, 25, 2014The Author

Conor Lenihan is a former Fianna Fáil – as were his brother, father, grandfather and aunt. Because of his insider knowledge, this first complete biography of Reynolds the politician/entrepreneur/impresario contains many insights into governmental intrigues, business machinations and political skullduggery.

Lenihan obviously liked and admired Reynolds, but this does not prevent him from unmasking some of the former Taoiseach’s scheming and plotting — and indeed his risktaking, sometimes for the very highest stakes.

The book covers a formative era in Irish history, and is a compelling read, not least because Albert Reynolds’ life had perhaps more ups and downs than most.

Reynolds’ story, as told by Conor Lenihan, is perhaps a prime example of Enoch Powell’s verdict on the life political. Powell, The Ulster Unionist MP for South Down 1974-1987 said of Joseph Chamberlain: “All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs.” He could easily have been talking about Albert Reynolds.

Albert Reynolds: Risktaker for Peace by Conor Lenihan (Merrion Press, £19.99)