The EU has advised its 450 million citizens—including over five million in Ireland—to stockpile essential supplies sufficient for at least 72 hours. Though the guidance is directed at EU member states, it may well be prudent for neighbouring Britain to heed the same.

The recommendation is part of a broader European Civil Protection strategy to boost preparedness for crises such as armed conflict, cyber-attacks, climate-related disasters and pandemics.

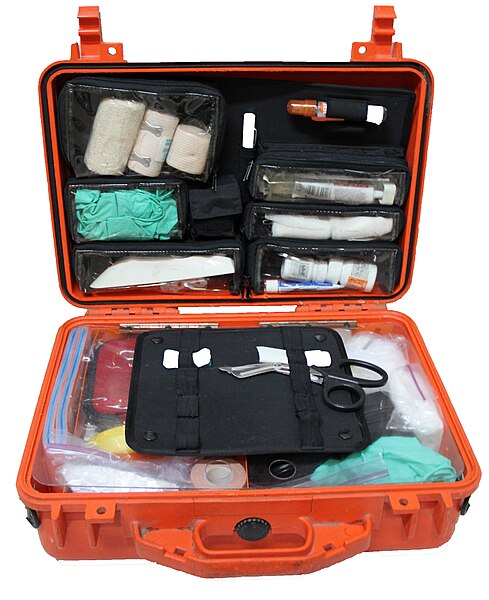

European Commissioner for Crisis Management Hadja Lahbib stressed the importance of preparedness, urging citizens to develop household emergency plans and maintain a three-day supply of non-perishable food, bottled water, essential medications, first aid kit, flashlights, identification documents, and battery-powered radios.

Experts also advise households to tailor emergency kits to their specific needs—taking into account infants, elderly family members and pets.

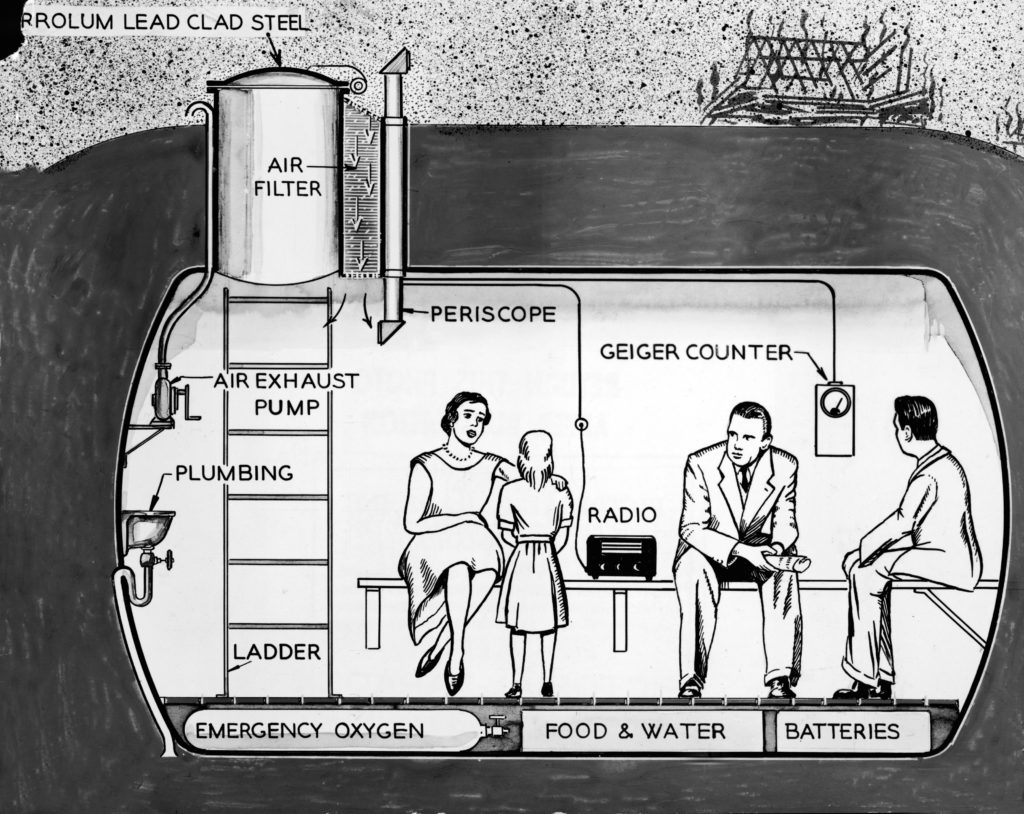

This initiative mirrors long-standing practices in countries like Sweden and Finland within the EU, and Switzerland and Norway in EFTA. In Switzerland, for instance, it is common for homes to include small underground nuclear fallout shelters stocked with rations and supplies.

Vital medications as recommended by the EU (image Wikimedia Commons)

Vital medications as recommended by the EU (image Wikimedia Commons)In Ireland, the EU guidance has prompted renewed debate about national readiness. Despite Ireland’s long-standing military neutrality, concerns linger about potential knock-on effects should neighbouring nuclear powers like the United Kingdom or France come under threat. Ireland's west coast is also seen as vulnerable.

There have been calls for the Irish government to establish strategic reserves of key resources such as medical supplies, energy, and transport infrastructure to ensure an effective national response in a crisis.

Public reaction in Ireland has been mixed—some see the EU advice as sensible given current global instability, while others are sceptical about the likelihood of direct impacts on Irish soil.

A far cry from 2001

The contrast with previous Irish emergency planning is stark. In January 2001, then-Minister for State Joe Jacob appeared on RTÉ Radio 1’s Marian Finucane Show to discuss Ireland’s response strategy in the event of a nuclear incident—prompted by public concern over the nearby Sellafield nuclear facility just across the Irish Sea in England.

Tasked with reassuring the public about Ireland’s emergency preparedness in the event of a nuclear disaster, Jacob instead fumbled through vague answers and baffling advice. As Finucane pressed for clarity, listeners were left stunned by the seeming lack of concrete plans.

Minister Jacob struggled to explain basic procedures, repeatedly referring to leaflets that hadn’t yet been distributed and advising people to tape up windows and doors with no clear rationale. To show he meant business he even rustled the fact sheets so that Marian Finucane would know they existed and would soon be in the nads of citizens.

Finucane, calm but increasingly incredulous, pushed for specifics—how would people in rural areas cope?

A befuddled Jacob’s vague reassurances only deepened public concern. She put it to the minister of the hypothetical situation of Sellafield suffering an explosion and an easterly wind bringing nuclear fallout across the Irish Sea to Ireland. “What would we do first of all?” asked Finucane.

This somewhat caught Minister Jacob off balance; it appeared to be something the government—or he at any rate—had not considered in great detail. He said: “The first point of contact is the gardaí, er, the gardaí communication centre. That's the. . . that's the contact point and, and, the, well. . . that's where the emergency plan is initiated. As soon as we get an alert, that's where the thing steps into gear.”

This did little to mollify Finucane: “What steps in? The emergency plan? What is it? What happens?”

Minister Jacob had no cogent guidance, and carried on for another excruciating 15 minutes, including a meandering brief on iodine tablets that would be distributed as part of the emergency response plan. The iodine tablets were not yet available, and no practical mechanism was in place for getting them to the public, but a very flustered minister said that people should stay indoors and listen to the radio — and all would be well. Deffo.

Back to the future

Ironically, in the early 1960s Ireland arguably took the threat of nuclear attack more seriously. Following the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the Irish Civil Defence issued a detailed booklet: Advising the Householder on Protection Against Nuclear Attack (Booklet No. 10).

Its practical tips included: build a fallout shelter, keep a survival pack, and—if caught in a nuclear flash—“PROTECT YOUR HEAD! TURN YOUR BACK TO THE FLASH! TURN YOUR COLLAR UP!” A stark illustration showed a figure with their collar up, sensibly facing away from the mushroom cloud.

Other advice included how to convert your kitchen table into a makeshift fallout shelter by draping it with painted bedsheets. In larger households, even the tea trolley might be drafted into service.

Compared with such advice from six decades ago, the EU’s recommendations may seem mild—but perhaps no less necessary in a world where threats have become less predictable but no less real.

In light of these earlier forays into protection from nuclear fallout, the EU’s advice last week seems relatively sensible.

Early 1960s pamphlet with cross-section illustration depicting a family in their underground lead fallout shelter

Early 1960s pamphlet with cross-section illustration depicting a family in their underground lead fallout shelter(Unknown photographer, from the collection of Pictorial Parade/Getty Images)