IRISH woman Liz Deasy was just a teenager when she joined the fight against racial segregation that was running rampant in a country almost 9,000 miles away.

In 1984 Ireland, an era without social media and the internet, the Clondalkin native was entirely unaware of the four-decade long plight of non-white South Africans facing a political system of apartheid.

A 17-year-old Dunnes Stores employee at the time, Liz unintentionally joined what began as a small-scale movement in Dublin but became something that left lasting legacy on both Ireland and the anti-apartheid movement 31 years on.

It would also lead her to meet the first black President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela.

On a beaming summer’s day that same year, shop steward Karen Gearon gave a union instruction to her colleagues not to handle South African goods, in protest against the country’s apartheid regime.

When 21-year-old checkout employee Mary Manning refused to process some fruit through the till, she was suspended and nine of her colleagues joined her as she walked out.

“I remember it fairly well, I was only a part-timer, I remember going in that day,” she said. “The suspension had already happened, I was only walking in as they were all preparing to walk out.

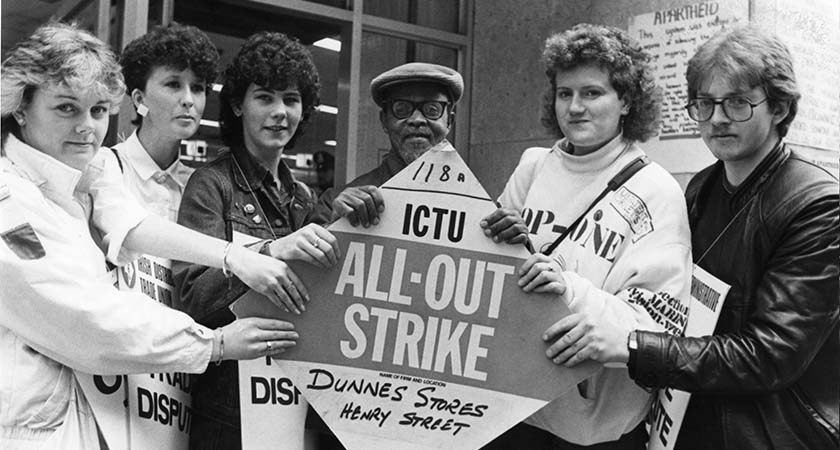

Dunnes Stores workers on strike outside Dunnes on Henry Street with anti-apartheid activists in 1985 (From L to R: Sandra Griffen, Alma Bonnie, Karen Gearon, Nimrod Sejake, Mary Manning and Tommy Davis) (Photo: RollingNews.ie)

Dunnes Stores workers on strike outside Dunnes on Henry Street with anti-apartheid activists in 1985 (From L to R: Sandra Griffen, Alma Bonnie, Karen Gearon, Nimrod Sejake, Mary Manning and Tommy Davis) (Photo: RollingNews.ie)“I remember Karen came over to me and said, ‘when you come into work tomorrow you don’t have to pass the picket line’. I was planning on going out with them anyway. We never knew it would last until two summers after that.”

Despite having no prior knowledge about the racial hierarchy that governed South Africa as a result of apartheid, Liz felt a personal attachment to the cause after meeting Nimrod Sejake, a political refugee in Ireland during the 1980s.

“I had no idea what I was doing, no idea,” she said. “It was a union instruction I was just following, I hadn’t a clue why. I was living the teenage life. It was only when we came out on strike that we met the likes of Nimrod who educated us about the apartheid system.

“The more we heard the stories the more we wouldn’t back down. They’d been through so much, what we were doing; we didn’t think we were doing much in regards to what they had been through. It made us stronger and more determined to stick together.

“Nimrod lost his family and was never allowed back in his country, Nelson Mandela was in prison for fighting for the colour of his skin, for his people. And then here we are in Ireland; I have the security of my home, my parents. To me striking was insignificant in terms of what they’d lost. We just knew we couldn’t back down.”

Hearing that Mandela became heartened during the latter years of his 27-year stint in prison due to their strike led the group to fight harder, together, to make a difference.

The days spent on the picket line outside the Henry Street store also brought to the fore the racial ignorance of some Irish people who blasted their campaign.

Former South African president Nelson Mandela praised the efforts of the Dunnes Stores strikers (Photo: Getty Images)

Former South African president Nelson Mandela praised the efforts of the Dunnes Stores strikers (Photo: Getty Images)“When we went out on strike in 1984 I never regarded this country as racist, but the amount of racist people we met on that picket line was unbelievable, because I didn’t grow up with that. It was horrific, it opened my eyes amazingly so,” Liz said.

“We had really bad days on the picket line but nobody ever even suggested calling it a day and walking back in, so we were always strong for each other.”

The Irish Government announced a ban on the importation of South African goods at the end of 1987; two years and nine months after the workers originally went on strike.

Liz believes its testament to their determination and self-belief that they made their mark in history.

“People can look at us and think if this is what a group of young women can do if they stick together, we were a minority of people,” she said. “We succeeded in more than what we set out for.

“The turning point of our movement was when we went to South Africa even though it was against the anti-apartheid movement who didn’t agree with us at the time.

“But the fact that we got deported back really honed into the world as to why is South Africa not letting these teenagers into the country. If they had let us in we’d never have got half the publicity we did. Then the world thought something is not right, they’re obviously hiding something.”

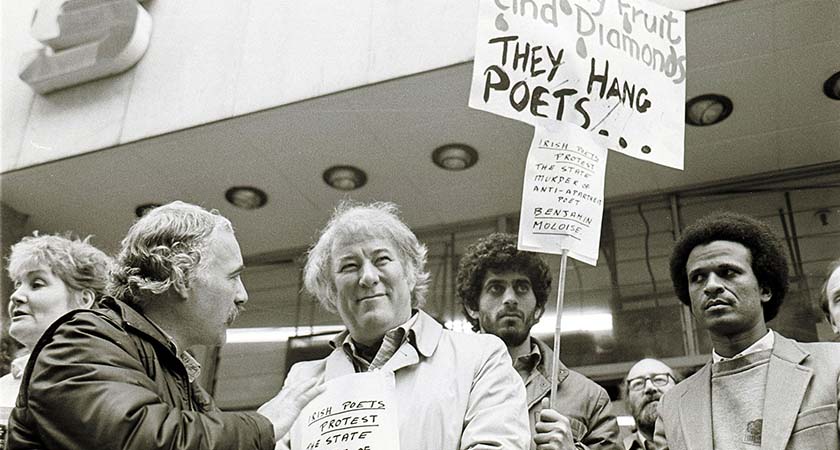

Irish Poet Seamus Heaney (3rd R) with Dunnes Stores Workers at an anti apartheid demo in 1985(Photo: RollingNews.ie)

Irish Poet Seamus Heaney (3rd R) with Dunnes Stores Workers at an anti apartheid demo in 1985(Photo: RollingNews.ie)Three decades on, Liz’s story and that of her fellow Dunnes Store workers’ anti-apartheid strike is heading to the London stage.

Next autumn, the Ardent Theatre Company is bringing the show, which was originally performed in Dublin in 2010, to a fresh audience.

Following the first reading of the script at Park Theatre in Finsbury Park, London, Liz said it was as though she was reliving 1984 all over again.

“It was very emotional, it was a very powerful, powerful play,” she said.

“The fact that Nimrod wasn’t with us made it even more emotional, because he was such a big part of our strike and we built such a great relationship all of us together.”

As a young woman thrust into the media glare, braving abuse on the picket line, and struggling to find employment in the aftermath of the strike, does she have any regrets?

“It made me the person that I am today,” she said. “And I got to meet Nelson Mandela, one of the greatest people to have ever lived, not many people can say that.”