THIRTY years ago, an explosion occurred at a nuclear power plant in the Ukrainian city of Pripyat.

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant disaster killed 31 people directly on April 26, 1986, but the lasting effects of the mass radiation pollution is still being felt around the world.

One of the plant's nuclear reactors exploded in the early hours of April 26 while engineers carried out an experiment to test how to reactors would hold out during a power cut.

The city was evacuated the day after the disaster as radiation levels in the atmosphere hit lethal highs - 400 times more deadly than the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima in Japan during World War II.

Exposure to the radiation led to life-changing, horrific injuries - the Ukrainian government estimated in 1993 that some 70 per cent of its population were unwell with illnesses ranging from respiratory to nervous system diseases.

Ukrainian women gave birth to severely deformed children and the rate of thyroid cancer saw a marked increase.

To this day, the lasting effects on people's health remains a topic of study for health professionals.

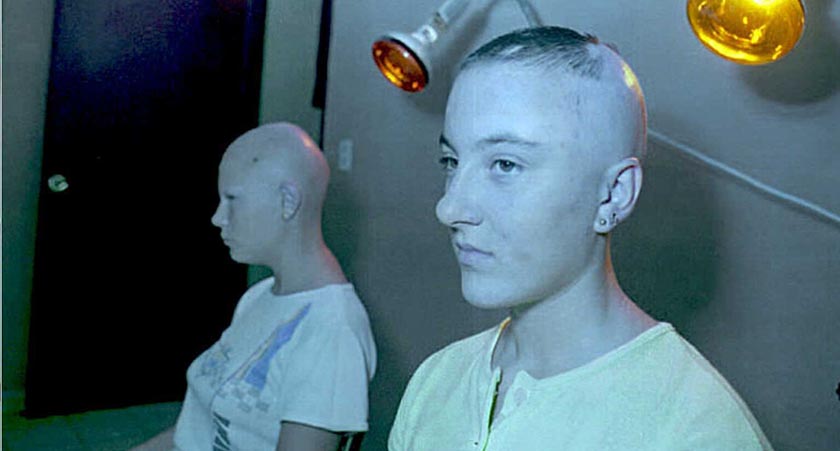

Oxana Gaibon and Alla Kozimierka receive infrared radiation treatment. (Photo: ADALBERTO ROQUE/AFP/Getty Images)

Oxana Gaibon and Alla Kozimierka receive infrared radiation treatment. (Photo: ADALBERTO ROQUE/AFP/Getty Images)The devastating effect on Chernobyl led to countries around the world taking in victims of the disaster - including Ireland.

Irish humanitarian worker Adi Roche went to the city in the immediate aftermath of the explosion and began working with those affected.

Soon after, she established Chernobyl Children International (CCI).

Her organisation was set up in 1991 with one simple aim - to get the children of Chernobyl away from the high levels of radiation in the country.

"My life’s work has been to develop programmes that restore hope, alleviate suffering and protect current and future generations in the Chernobyl regions," Ms Roche says.

"CCI is founded on hope and courage: the hope that the children—one by one and heartbeat by heartbeat—will thrive; and the courage to envision and create a better world."

Since then, Irish families have adopted and fostered children from the area and Ireland and Chernobyl's relationship has been firmly formed.

Each year, CCI brings dozens of children to Ireland for a short period of time to allow their bodies some respite from the radiation levels that, even 30 years later, are still dangerously high.

Pope John Paul II meets with children of Chernobyl. (Picture: JANEK SKARZYNSKI/AFP/Getty Images)

Pope John Paul II meets with children of Chernobyl. (Picture: JANEK SKARZYNSKI/AFP/Getty Images)Irishwoman Julie Bond this week spoke to BBC Northern Ireland about her memories of Chernobyl.

The Antrim town native, who now lives in Co. Wicklow, was a student at the University of Surrey in the 1980s and at the time of Chernobyl was on an exchange trip to Kiev.

Officials at the university grew concerned about its students and two days after the disaster, flew them back to London.

"When we got into Heathrow, we had a complete health check," Ms Bond said.

"Some of our clothing was removed, including my jumper, because it read over 100 on the Geiger counter, that measures radiation.

"We were all told that we were fine, but that perhaps it might be a good idea to have a health check in five or 10 years."

Since her time in Chernobyl, Ms Bond had to have her thyroid removed because of cancer and has given birth to three children - one of whom has Down's Syndrome.

Despite medics not specifying that either of these things is related to her time in Kiev, she is unsure.

"I think medics seem to be very quick to say it's nothing, which is great if it's not, but I don't know if that's true," she said.

A picture taken on April 22, 2016 shows a deserted residential building in the "ghost town" of Pripyat near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. "Picture: GENYA SAVILOV/AFP/Getty Images)

A picture taken on April 22, 2016 shows a deserted residential building in the "ghost town" of Pripyat near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. "Picture: GENYA SAVILOV/AFP/Getty Images)Today marks 30 years since the explosion and Pripyat remains a ghost city.

Many of those who survived the disaster still suffer with the long-term effects on their health - and generations of children with congenital deformities have been born.

The World Health Organisation estimated that anywhere up to 985,000 people have died from cancer as a direct result of the exposure to radiation.

Commemorative events are taking place in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia today to mark the anniversary - and CCI are gearing up to bring more children over to Ireland this summer.

Ms Roche will speak to the United Nations today in their general assembly as she continues to work to make the Chernobyl exclusion zone safe for those left behind in Ukraine.

Though three decades have passed since the world's most deadly nuclear disaster, the legacy of Chernobyl lives on - in Ireland and around the world.