THIRTY years ago today a strike described as the “most bitter industrial dispute” in British history came to an end.

Led by Arthur Scargill and the National Union of Mineworkers, the strike by the men who had spent most of their lives working down the pits at collieries across Britain began in 1984 and ended on March 3, 1985.

It followed years of increased tensions between unions and mineworkers and the government after the election of Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister in 1979.

The newly elected government became heavily involved the mines in the 1980s, before announcing on March 6, 1984 its intention to close 20 coal mines immediately, with a longer term goal of closing another 70 pits.

In response, the NUM and its members launched a series of walkouts and strikes began in earnest.

Among them the strike at Orgreave Colliery in South Yorkshire was well documented, where the NUM organised a mass picket of the British Steel coking plant which brought out 6,000 workers on June 18, 1984.

The police, who sent in more than 4,000 officers to manage the crowd, were later forced to pay £500,000 in compensation to 39 miners who were arrested during the events of the day.

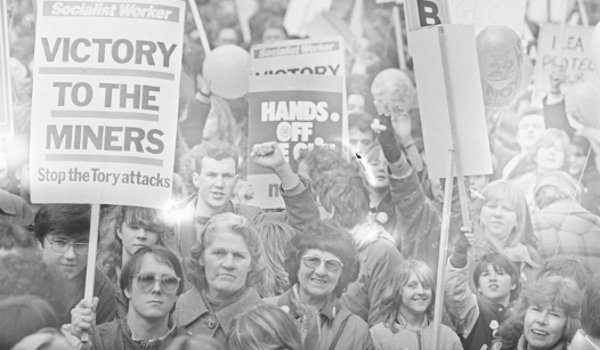

One of many rallies held during the miners' strike of 1984-5 by supporters of the cause (Photo Getty Images)

One of many rallies held during the miners' strike of 1984-5 by supporters of the cause (Photo Getty Images)Among the working class families involved in the strikes of 1984-85, many who had known nothing other than the colliery being the lifeblood of their community, were a number of Irish men and women who had moved to England to find work and made their homes around the pits that employed them.

It is a journey that was being made for centuries to Britain’s mining towns, according to Mike McNamara, Cultural Officer at the Brian Boru club in Wigan.

When the 121-year-old club’s committee was formed in 1894 the town was attracting Irish men seeking work in its developing coal-mining industry.

As the number of pits grew so did the Irish contingent settling in the area, which is in Greater Manchester, in order to mine them.

“Around the time of the club’s opening the Irish were coming here for the cotton mills, where the ladies worked, and the coal, as the men went done the mines,” Mr McNamara explains.

“Our club was formed as a response to that – it was a place for the men to come together to socialise, talk of home and relax after very strenuous work. Eventually the women were able to join them and you soon had the foundations of our thriving club which is still going strong today,” he added.

In Maltby, South Yorkshire, Seán Carney was among many born in the mining town to Irish parents; men and women who had left their homeland and found work in Yorkshire’s pits and the communities serving them in the 1920s.

His late father Hugh Fergus, who had travelled to England from Mount Charles in Co. Donegal in search of work in 1920, worked in mines in Doncaster and Rotherham before settling in Maltby in 1928.

There he and his Rotherham-born wife Doris raised their family for 35 years, before relocating to Scarborough.

For Mr Carney the memories and the makeup of Maltby is as Irish as any town back home, due to the volume of Irish working the mine and the large families and networks that grew around them.

It is a history he was keen to document and as the final nail was placed in the legacy of the Maltby mining community by the closure of its pit in April 2013, Mr Carney was in the process of releasing his first book.

The Yorkshire Irishman dedicated the 100-page tome, entitled The Forgotten Irish – A History of a South Yorkshire Irish Mining Community, to his parents.

In it, he states:

“My father, a bold, dark wavy-haired handsome native of Donegal was never one for great demonstrations of affection.

But every day of his working life, as he readied himself for another shift at the coalface, he would pull on his coat in the hallway of our terraced house in the heart of Yorkshire, some 400 miles from his homeland.”

He adds: “Without exception, whether it was a day, afternoon or night shift my father was preparing for, my mother would always be by his side anxiously waiting to say her goodbyes.

He would gently kiss her, bless himself and, without daring to look back, walk out the door to start his shift.

They were the only times I ever saw mam and dad kiss in their 55-plus years of marriage.

But it was no doubt a scene repeated in scores of terraced homes across Maltby and beyond.

No matter where they called home, as every miner left behind their loved ones in readiness to plunge into the darkness and far, far into the bowels of the earth, the only certainty was that not one of those brave souls could be certain they would ever see daylight or their families again.”

This week, as the anniversary of the end of the miners’ strike falls, Mr Carney recalled his father once again.

“Many miners would have been retired by the 1980s and being pensioners would certainly not have had the will for rioting,” he told The Irish Post.

“Alas, Irish miners of my dad’s age would have been dead and gone by then. However, they were no strangers in the long standing struggle for better wages and safer working conditions underground.”

He added: “During the strike I belonged to a miners support group-raising funds and collecting food for the families and workers.”

A number of books have been published this week to mark the 30 year anniversary of the end of the miners’ strike, including From a Rock to a Hard Place by Beverley Trounce and Robert Mercer-Nairne’s new novel about the strike and the politics of Thatcherism, The Storytellers: Metamorphosis.