HAVING publishes his long-awaited book documenting his lengthy career spanning naval service, the NATO Presidency and a pivotal role in Parliament during the conflict in Northern Ireland, Sir Patrick Duffy reflects on a life ‘blessed’ by being both Irish and British.

The former Labour MP for Sutton Attercliffe was also Minister for the Navy before swapping his Westminster career for the NATO Presidency in the 1980s.

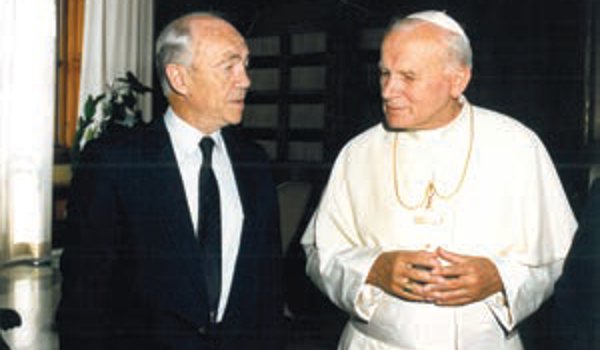

That post opened the door to a new range of achievements and experiences — including audiences with everyone from Pope John Paul II to Margaret Thatcher.

But for Sir Patrick — Yorkshire raised but Lancashire-born to Irish parents working England’s coalfields — the overriding pride in his many achievements falls largely to his own enduring sense of being at once both British and Irish.

His book Growing up Irish in Britain and British in Ireland documents just that.

“WHATEVER the title of my book an early sense of Britishness had stirred me in Wigan, where I was born, and later in the Yorkshire coalfield.

It was stimulated on the outbreak of World War II, when I soon found myself voluntarily serving as a teenage ordinary seaman in the battle-cruiser ‘Repulse’.

It was strengthened when I was selected for officer training and opted for the fleet air arm — never dreaming that one day, as Minister, I would take the chair of the board of admiralty.

To have been preserved during hazardous squadron service and then later to tread the historic flagstones at Westminster when I arrived in the House of Commons left me feeling deeply honoured.

I was honoured also as president of the NATO assembly to witness our continent take leave of the tragic paralysis of the Cold War and to do so in active association with all the leading players — from the White House and the Pentagon to the Kremlin and the Soviet General staff, as well as contrasting meetings with Prime Minster Thatcher and the Pope.

Sir Patrick Duffy with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican in 1989

Sir Patrick Duffy with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican in 1989I recall easily Margaret, despite my earlier challenge to her hunger strike policy in the North of Ireland, poured me not only one cup of tea, but two — to the horror of her staff, who were watching the clock — whilst John Paul set about me in his private study because of spending on arms that he insisted should go to the Third World.

I remember very well leaving that meeting and having him call behind me ‘remember the Third World’.

For all my apparent Irishness, I was now actually exercising with pride a British presence and authority on such missions. I was proud also to represent the Attercliffe division of Sheffield in Parliament.

For generations its people had produced guns and protective armour for the Royal Navy.

It was only after joining an aircraft carrier in Belfast while still in service that I first sensed something was not right in the North. As officer of the day, I found myself instructing sailors going ashore that certain streets were strictly out of bounds…

Funnily enough I never served in a ship or squadron without encountering men from the south of Ireland serving there too.

And when I was eventually granted extended sick leave and travelled to Co. Mayo on crutches, I found awaiting me at Holyhead a ship’s gangway reserved for Irish servicemen — enough of them to warrant their own sailing back home.

Such a growing awareness stirred further my Irishness, and involvement in the conflict in Northern Ireland gradually taxed my Britishness.

My later appointment as a defence minister had given me a stake in the province and entitlement to classified briefings on the North.

But rather than look back in anger at Westminster I believed that the time had come for Ireland to seek a mutually productive relationship with Britain, starting with trade.

Accordingly, I tried to interest parliamentary colleagues with an appropriate Early Day Motion, to which Lord Hattersley and Kevin McNamara were signatories.

It is interesting to reflect on that now, as Ireland is currently Britain’s fifth largest export market, with Britain the largest market for Irish exports. And Ireland’s recent Economic recovery has made it once again the Eurozone pin-up.

"When England play Ireland at rugby or football please don’t ask me which I support”

"When England play Ireland at rugby or football please don’t ask me which I support”That said, elsewhere in those days, in the ’70s and ’80s, the treatment of the Irish in Britain had become a serious problem.

For it affected not only blameless citizens but political debate and arguably an incipient peace process for which some of us had striven in support of John Hume from the beginning.

There were thankfully some comforts arising for the community.

The Irish Post and its distinguished editor, Brendan Mac Lua, with his fearless news presentation, had become a source of strength.

The Federation of Irish Societies began to function as a nationwide organisation. Soon the hurt felt by many Irish in Britain actually forged a common loyalty and created a sense of community.

Other varied inputs have also been outstandingly successful and helped transform relationships over the years.

To mention a few, the pick and shovel contribution of Irishmen has since given way to their actual presence in company boardrooms — well highlighted in people such as John Kennedy and Andy Rogers.

Elsewhere, in publishing [the Labour Party policy document] Towards a United Ireland in the mid-80s, the joint leadership of Neil Kinnock and Lord Hattersley, together with their shadow spokesperson Kevin McNamara, displayed a surer touch than any other Labour leadership, before or since.

Such inputs, including the nurturing and consoling of the Church for the newly-arrived in Britain, has made me exceptionally proud of my own Irish background, although my allegiance to Britain remains immovable.

Therefore identity for me has become a matter of balance; on clear days in the middle of the Irish Sea I can actually see both the Welsh and Wicklow mountains.

I always feel that I am blessed to be part of both and I recall the words of the Queen during her remarkable visit to Ireland, when she reminded us that the ties that unite the Irish and the British are stronger than their historical animosities.

Also, Taoiseach Enda Kenny told me, in a private conversation behind a door in the Irish Embassy in London earlier this year, that Ireland’s friendship with Britain has become altogether closer since the Queen’s visit.

Thanks to being brought up Irish in Britain and British in Ireland I found myself identifying with Queen Elizabeth and President Mary McAleese during that visit, and I would unhesitatingly serve both.

But when England play Ireland at rugby or football please don’t ask me which I support.”

Sir Patrick Duffy was speaking in conversation with Fiona Audley

Growing up Irish in Britain and British in Ireland: and in Washington, Moscow, Rome and Sydney is published by Jeremy Mills Publishing Limited.