FORGET all of the twee clichés about emigrant life in north-west London during the 1960s … the real story is darker – and far more interesting according to local historian and author Bernard Canavan.

The bar is quiet, save for the spoon clinks of tea and coffee being stirred. The waitress taps a jug of hot milk on the counter, tips high and pours long.

She carries the tray through to the front bar of The Crown Moran Hotel, past a painting on the wall which depicts a scatter of terrified people tumbling from an airplane and down onto suburbia.

They’re Irish. It’s London. It’s Cricklewood.

Inside, the painting’s creator, Bernard Canavan, is sat in the morning quiet of a bar with a noisier Irish history than arguably any other public house outside of the Republic.

The old walls of The Crown leak rich stories of emigration that have spilled out the door, onto the Broadway and into Irish social consciousness.

The Broadway is part of the A5 routeway, originally built by the Romans in AD, and it’s a straight 200-mile run to Holyhead, past Barretts pub and away.

The road, like the past, has been built upon by layers of emigration.

In Manchester, Cheetham Hill was home to the Irish before it became home to the Jews. Now it’s home to a large Asian community.

Emigration restocks.

And so it goes in this London ward quickly shedding an Irish reputation and taking on one of cultural diversity now full of people with a different route in than the A5, from Romania, Poland, Afghanistan and the Philippines.

“When you are an emigrant, you are on the street to start off with,” says Canavan, who is regarded as one of the seminal voices of London’s recent Irish history.

“You look outside the window now and there are Polish and Romanian migrants doing the same as what Irish migrants did when they came; waiting to get picked up for work.

“When migrants come first they are visible and they are on the street. The places they find work are in some way connected to the streets: cafes, bars, working on the roads.

“Cities continually reprocess migrants. This is what is happening in Cricklewood now.”

Once, the Broadway spun a thread of Irish eating houses where “Irish workers would order half a pound of steak and it would come with about 10 potatoes,” Canavan adds.

“Now a lot of the food has been replaced by fruit and vegetable stalls, signs for Halal meat.”

Why Irish emigrants decided to settle in Cricklewood is a matter of speculation, but this is a route-way that has starting blocks in a Ferry Port and a finish line within touching distance of Central London.

It’s been said that the reason Irish people settled in Camden Town was because it was the furthest someone could walk from the train station carrying two suitcases.

Ultan Cowley, the author of the Men Who Built Britain, suggests that where people put down roots is sometimes that simple.

Canavan remembers the signposts for departure being as straightforward. There were schooldays in Longford when the teacher would point at the students and say: ‘You Kilburn! You Cricklewood! You Kilburn!’

“He knew where we were all going because we had no money,” he says. It was recognised at every level in society where we were going and he was right.”

Canavan found a different life on the Broadway and other Irish centres in London to the one he left behind in the early 1960s.

“You have to remember that in some parts of Ireland, the bike and how far you could cycle was the limit of your world.

“Ten miles out and ten miles back, that was your reach into another life. But England seemed to offer great freedom, the prospect of girls, jobs, money, beer; things that had been rationed in Ireland.

“There was no one to look after you, but at the same time, there was no one to look over you either.

“Which meant there were things you could do in England that you certainly couldn’t do in Ireland.”

Social norms that defined life in Ireland were redefined on the Broadway.

“There was a revolution of Irish values but it was the ending of Irish values over here,” he says.

“Romantic Ireland isn’t buried with O’Leary in the grave, it’s buried in Kilburn and Cricklewood and the graveyards of England.”

He arrived in the 1960s, it was a time when Americanization found a conduit in Britain.

Music was changing, fashion flourishing, courtship too and of course, attitudes to sex.

“There was a sexual revolution in the ‘60s for everyone.

“You had the opportunity to live the atomized city life and still be Irish.

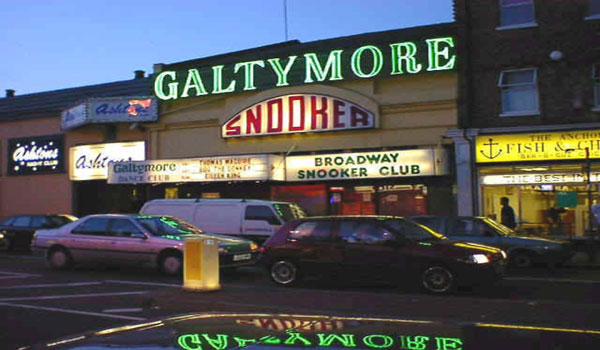

“Ballrooms like the Galtymore were lively places and they were symbolic of that life.

“But there were a lot of difficulties negotiating face-to-face contact with people, where previously it was done by families and parents.

“The old courtship expression in Dublin was: ‘Will you fix me up with your sister.’ That changed in England where there were crowds of people.

“Did sex come to the forefront? Of course it did.

“Even when you transgressed nothing happened. You could leave your wife and remarry and it was socially acceptable. The children of Irish parents born here would be sent home for the summer and the grandmother would ask what was going on in England.

“At a low level, they might discover their Irish son or daughter didn’t go to mass regularly anymore, or that a family might be breaking up, or someone had had an affair, or a child with someone else, which would have been anathema.

“But because it was socially acceptable here, it had to become socially acceptable in Ireland.

“Otherwise parents would have to disown their children in London.

“I remember a friend of mine coming knocking at the door at about 7am and telling me he was in deep trouble: ‘Some lassie I met a week ago is telling me she is pregnant.’ He said. He was thinking of doing a runner. That was the way people reacted.

“But here there was backstreet abortion and Irish men realised that they would have to use contraception and women would have to go on the pill.”

Canavan recalls the sometimes cheap celebration of sexual conquest in bars “shared in the crudest possible forms.

“It was a world of leg over discussions, not any sense of the girl or who she was.”

He explains that a huge amount of Irish women choose to marry ‘out.’

“Which meant an awful lot of Irish men married English women, or they just didn’t marry at all. They went to the pub which was an employment agency, a place to change cheques, an eating house, it was everything.”

The environment was raw and not for the faint hearted.

“It was a very macho world. There were lots of fights which were quite violent and the image men wanted was of being tough. There were places I would not have come in at that time. You would see people spewing out into the streets and people were beaten.

“There was a modernity to city life, a self-centeredness that people learned and they had to learn. You have a practical identity and that’s what becomes important.

“I remember being in a lodging house and the woman came in with a big plate of food and I politely offered for the rest of the people to go first. The whole plate was cleared. There was nothing left. From this point I realised this was the new logic.”

The web of houses that ran off the Broadway housed thousands of Irish now pouring into the postcode. Accommodation was plentiful but often overcrowded.

There was work. Money was sent home. There was exploitation.

“I had never met anyone from Donegal before I came to London so there were people from places at home that were alien to many of us. This encouraged exploitation.

“We didn’t have solidarity... a lot of that is romantic.”

Romantic, rough, call it what you will, this world is gone. “There’s not much left now of the Irish influence on the Broadway and when we talk about the Irish of Cricklewood today, we are talking about a world unrecognizable from the 1950s emigrant.

"Gradually, Irish people moved up the social hierarchy. The Irish have worked their way into the fabric of the city and Irishness is not so perceptible now because there has been assimilation into multi-cultural Britain. There are Irish faces on the Broadway but Commonwealth emigration changed the whole thing.

"We are not talking about an exchange of people, the English did not disappear then and neither have the Irish now, they have just been absorbed into a society that’s multi-cultural.

"There is a sense of having plateaued but that’s not so disappointing. That’s assimilation.”