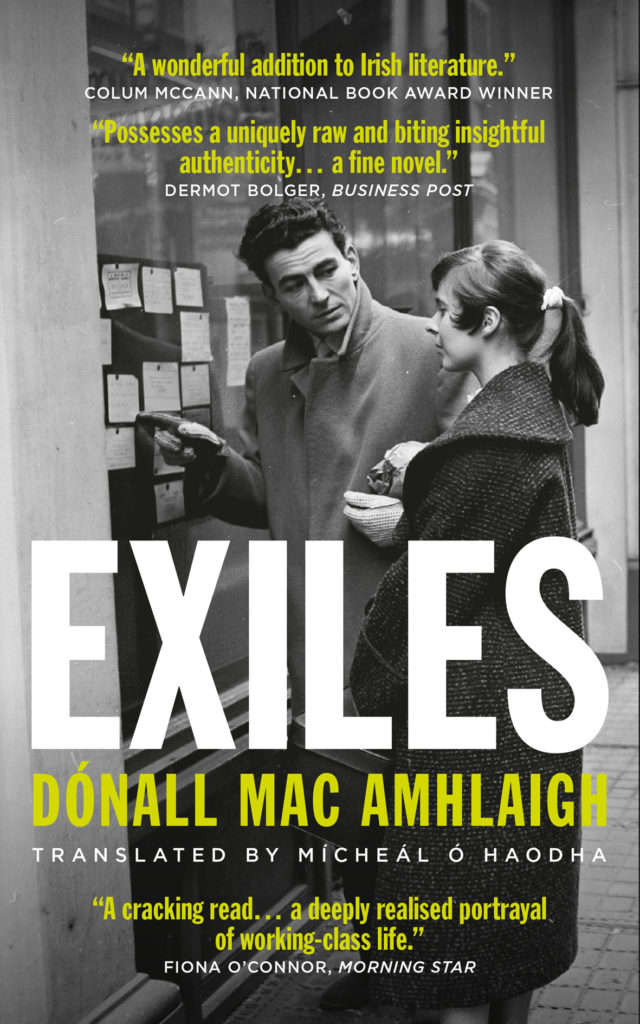

DÓNALL MAC AMHLAIGH’S autobiographical novel Exiles is a powerful documentation of the experiences of the Irish men and women who arrived in post-war Britain and created new lives here.

Written at a time when the Irish were “building England up and tearing it down again,” and teeming with the raucous energy of post-war Kilburn, Cricklewood and Camden Town, the novel is described as “one of the very few authentic portrayals of working-class life in modern Irish literature”.

Mac Amhlaigh was among that crowd, working on construction sites throughout London and the Midlands, including the M1 and M6 motorways.

In his book he features the people who were around him, who later calcified into stereotypes of Irish immigrants and their haunts: the navvy, the drinker, the fighter, the nurse.

The Galway author’s acclaimed work has recently been translated from Irish into English by Mícheál Ó hAodha, a fellow Galwegian, poet and author.

And the re-release is receiving critical acclaim across the board - with Dr Tony Murray, Director of the Irish Studies Centre at London Metropolitan University, among those heaping praise on the project.

“I cannot stress strongly enough the importance of bringing this work to a wider readership,” he said.

This week Ó hAodha shared an excerpt from the book with The Irish Post…

THOUSANDS of people leaving forever on the immigrant boat!

This was more than a catastrophe! It was a form of treachery to the ideals of the heroes of 1916 and the generations who’d come before them.

People were lashing into the drink heavily now, steeling themselves for the journey ahead. A few were already well-on-it and full of talk and bravado. Men leaned in on one another’s shoulders in that familiar fashion of the country people when they came together for a drinking session.

That tribal camaraderie that combined clannishness with a veiled sense of threat.

This race of people were a strange breed in the way their loyalty to one another could transform itself in an instant and break into argument: it was love/hate as two sides of the same coin…

Theirs was a unique culture, one that they’d somehow managed to salvage from ancient times and clung to even through the toughest of ordeals.

Their history was important. Their story deserved to be told.

To the left of Niall was a middle-aged man was who drunk and ready to sing – if anyone’d listen to him, that is!

The man suddenly threw his head back and shut his eyes, then began working his hands,

winding himself up to reach for the words of his song.

He was ready to sing and yet he was on edge. He’d a prickly look about him – it wouldn’t take much to start an argument with him.

‘Neós, an chéad lá den mhí is den Fhómhar, sea chrochamar na seólta …’

‘Well … now, on the first day of September, we hoisted our sails,’ he sang at the top of his voice, as if daring anyone to interrupt him…

‘Nár laga Dia thú!’ (May God never weaken you) someone calledout in a mocking voice and a few men looked over in disgust at him, much as to say that they resented this old-fashioned carry-on of his.

These latter men were the types who’d already spent a season or two working over in England, Niall suspected, because they were the types who’d little patience with the latest wave of emigrants – such as this singer – whom Niall suspected was probably leaving home for the first time.

The singer stopped suddenly and glanced around the room. His eyes settled on Niall and stared at him as if taking him in properly for the first time.

He swayed drunkenly but the next moment assumed a confrontational pose, as if to challenge this unwelcome intruder to the proceeding.

‘Up Muicineach!’ the man shouted out in challenge.

‘Up Down!’ Niall replied and someone skittered with laughter. Niall regretted his retort immediately. He knew how easily such smart-alec comments could start a row in a pub, and he’d never been fond of arguing or fighting.

The man gave Niall another dizzy stare but then his attention shifted away. He began to whistle a reel.

He’d an urge to dance now and so he drew his arms to his sides, pushed his two thumbs out in front of him and directed his eyes to a point somewhere at the far end of the room.

Then he launched himself forward drunkenly.

Niall backed out of his way and tried to attune his ears to the conversations that were going on around him.

What he heard disheartened him, however. All the talk related to England and to what life was like across the water.

These people had already left Ireland behind in their minds…

No, you f**r, you change in Birmingham, you’ve no business going to Rugby…On the beet son, to Peterborough. That’s where loads of the Mayo crowd go, those hoors are going there for years. And I don’t need to tell you, Bartley, you’re way better off with an English contractor. McAlpine or Wimpey or one of them.

Let the Irish ones go to hell, those b**ds would kill you with work … Yep, the hoors, they were getting two pounds a day, seven days a week. Government work, son…

Wasn’t Niall lucky that he’d been thinking ahead and saving for this day – so that he didn’t have to leave like these lot here?!

That would be his absolute last resort. He’d prefer to stay in an army uniform for the rest of his life than have to leave Ireland forever and be reliant on the English for his livelihood.

He must have some good stuff in him all the same, seeing as his plans had worked out and he’d managed to put a small bit of money aside lately.

I mean, there were plenty of distractions that he could’ve blown it on, no bother. Hadn’t Captain Delaney referred to him as ‘the entrepreneur’ – taking the piss out him?

He was jealous because he knew that Niall was putting his weekly wages aside and saving it,

whereas Delaney didn’t have it in him to save a single penny!

Every Wednesday, Niall had left a full two pounds of his wages sitting in the book and used the remainder to get him through the week.

This had been no mean feat when you saw your comrades heading down to town of a night and having good craic while you were left hanging around the barracks, stretched out on your narrow bed and staring at the ceiling.

It had been tough to hold out, but Niall had managed it despite everything.

That’s not to say that he hadn’t often been sorely tempted to give up and head out on the lash…

There’d been plenty of evenings when he’d been a right cranky b**ix because he was so sick

to the teeth of staying in; he’d been at the end of his tether often enough: that desperate for even one pint of the black stuff.

Never mind all the times he’d been dying for a smoke. He’d stuck to his plan all the same, and as the day of his release came closer, the temptation to break his strict regime had lessened and he’d sensed victory.

And signs of it now – he’d a nice little stash of money set aside for himself.

And he wasn’t dependent for his money on anyone else – whether Irish or English – unlike this poor legion of the dispossessed here now, all of whom had had no option but to leave home so’s they could earn a bit for themselves.

Paddy Delaney could say whatever he wanted about him – but the joke was on him now!

Niall finished his drink and glanced up at the Fallers clock above the bar.

He’d time for another drink. He didn’t need to be at the station yet.

Now that he’d the sweet taste of porter on his lips again he couldn’t believe how he’d managed to stay off the drink as long as he had; he’d never have believed he had that much willpower in him.

And as for the fags! The tobacco smoke worked its way down through him now

in a wave of pleasure. It was just beautiful.

Niall slammed his glass down on the counter and called another pint.

He felt slightly dizzy now – between the cigarettes and the drink – but it was a nice dizzy,

like a little dance of joy up and down his body.

The crowd was pressing in on the bar and Niall backed out of the way, pint in hand.

He was surrounded by people that would have stood out in any company.

Even the way they dressed was distinctive – never mind their language and

mannerisms. They had a wild half-subdued energy, something that distinguished them completely from people of other Irish regions.

It was this same energy and dynamism that stood them in good stead over on the plains of England, where they tore into the work with great energy – eager to prove themselves.

Exiles by Galway-born writer Dónall Mac Amhlaigh, translated from Irish by Mícheál Ó hAodha, can be purchased online directly from the publisher here or from Amazon and all bookstores.