ON OCTOBER 21, 1805, Britain’s Royal Navy claimed its most famous victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, but the Irish contribution to that day is often forgotten or simply not realised.

Half a century before the Great Famine wrought havoc, the Irish made up a third of the entire population of the British Isles - and their position as the Royal Navy’s second largest group reflected the booming numbers back home.

Though the largest contingent of the British force were Englishmen, more than a quarter of the Royal Navy’s 17,000 men were Irish.

Names such as Horatio Nelson and Cuthbert Collingwood were immortalised by the battle, but the sacrifices made by the Irishmen of Trafalgar have been little remembered in comparison.

One such Irishman was James ‘Jack’ Spratt, who was born in Dublin in 1771 to parents from Mitchelstown, Co. Cork.

Spratt joined the navy in 1796 as a wide-eyed 25-year old recruit, but quickly rose through the ranks to become an officer.

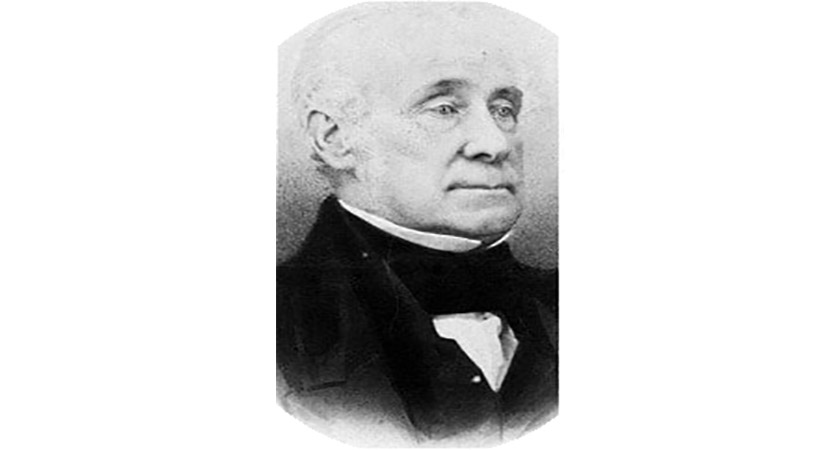

James Spratt was born in Dublin, and served in the British Royal Navy

James Spratt was born in Dublin, and served in the British Royal NavyHe was promoted to midshipman in 1798 and was already a veteran of the Battle of Copenhagen four years prior to the events at Trafalgar.

But it was his exploits on that day in particular which gained him fame, aged 34.

In the midst of the battle between the Royal Navy and the combined forces of the French and Spanish navies, Spratt dived into the sea from the HMS Defiance.

With his cutlass (a small sword to you and me) between his teeth, Spratt swam to the enemy ship, L’Aigle, and boarded her single-handedly through a stern window.

There, Spratt encountered the ship’s French crew, who attacked him. After killing two with his cutlass, Spratt fell with one of them down onto the lower deck – killing his opponent.

In the melee, Spratt was shot after deflecting a bullet off of his cutlass down through his leg.

Spratt was saved by the timely arrival of some 50 men who, inspired by his act of fearlessness, followed him onto the enemy ship.

Despite his gallantry, the injury to Spratt’s leg would end his career in the navy.

After surviving the Battle, Spratt’s wounded leg was placed in a padded box to allow it to heal.

When the box was opened, hundreds of maggots were stuck in his calf with only their tails visible to his surgeons.

Spratt refusal to have the leg amputated resulted in him living out the rest of his life with one leg three inches shorter than the other.

James 'Jack' Spratt photographed in his 70s

James 'Jack' Spratt photographed in his 70sAfter 17 weeks in hospital in Gibraltar, Spratt returned to England to work in a lighthouse near Teignmouth, Devon.

At Teignmouth, Spratt became renowned locally for his long-distance swimming skills – being commended on nine occasions for saving drowning men.

On one occasion he leapt into the sea and saved a drowning sailor who was being approached by sharks.

On his 60th birthday he swam 14 miles (24 kilometres) from Teignmouth to Brixham to win a wager he had made with a French officer.

Spratt was also one of the few survivors of Trafalgar who was photographed when the age of photography began in the 1830s.

By the time of his death at the age of 82, Spratt had had six daughters and three sons by his wife Jane, with his son Thomas becoming a world-renowned geologist and friend to Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Though his story is no doubt exceptional, James ‘Jack’ Spratt was just one of thousands of Irishmen who risked life and limb at the Battle of Trafalgar for a nation which often disregarded them.

His story, and the stories of all the Irishmen of Trafalgar, should not be forgotten.

(*Orginally published in 2016)