IRISH explorers stand at the heart of the epic story of Antarctic exploration, which is currently commemorating the 100th anniversary of Shackleton’s famous Endurance expedition.

It was an era of discovery echoing with episodes of unimaginable hardship, awe-inspiring endurance and incredible feats of survival. Yet the Irish heroes at the centre of the drama were quickly forgotten and shoved to the margins of history.

The men included the enigmatic Edward Bransfield, the unassuming Francis Crozier, the charismatic leader, Ernest Shackleton and the unsung hero Tom Crean. These men discovered Antarctica, mapped the frozen wastes and were the pathfinders who penetrated the brutal interior, but were soon forgotten.

These men sailed to the ice during Ireland’s period under British rule and after Independence, it was impossible to celebrate any association with the British. With striking symmetry, the age of Antarctic exploration ended with Shackleton’s death on January 5, 1922 — two days before Dáil Éireann ratified the Anglo-Irish Treaty of independence.

Bransfield and Crozier were already footnotes to history and those like Crean, Forde and Keohane, who together had served 80 years in the British navy, were compelled to remain silent about their exploits. Few books were written about these men, no statues were erected and their names faded from history.

Only now is Ireland starting to recognise these men. Statues have been erected to Crean in Anascaul, Crozier in Banbridge, Forde at Cobh, Keohane in Courtmacsherry and the McCarthy brothers in Kinsale. The cabin where Shackleton died will soon be placed on permanent display in Athy, Kildare.

1. EDWARD BRANSFIELD

Edward Bransfield came from Ballinacurra, near Midleton in Cork. Born in 1785, he was press-ganged into the navy during the Napoleonic Wars and served for over 20 years. In 1819 he was asked to take the small merchant brig, Williams, to investigate the sighting of unchartered islands south of Cape Horn and made the first verified sighting of the Antarctic coastline in January 1820.

Bransfield’s claim was challenged by the rival Russian navigator, Thaddeus von Bellingshausen, who had spotted land three days earlier. While Bransfield dutifully recorded his sighting, Bellingshausen was not certain and the controversy about who first sighted Antarctica rages until this day.

However, no portrait or photograph of Bransfield has ever been discovered and the face of the man from Ballinacurra who made the first definitive sighting of Antarctica remains a mystery.

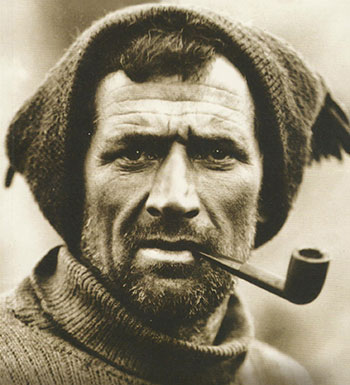

2. TOM CREAN

Tom Crean, from Anascaul, Kerry, was the unsung hero of Antarctic exploration. Born on a farm in 1877, Crean ran away from home to join the navy at 15 and served on three of the great expeditions in the early 20th century. He served with both Scott and Shackleton, spent longer on the ice than either and outlived them both.

Crean volunteered for the Discovery expedition in 1901 and was among the last to see Scott alive in 1912, just 150 miles from the South Pole. He returned to ice to bury his frozen body. Crean joined Endurance in 1914 and was one of Shackleton’s key men in the fight for survival after the ship sank. He made the open boat journey to South Georgia and marched across the island to bring rescue to his comrades marooned on Elephant Island.

His brother, a sergeant in the Royal Irish Constabulary, was shot dead as Crean returned to Kerry. As a result he never spoke about his exploits in the ice. Crean opened a pub, The South Pole Inn in Anascaul and died of a burst appendix in 1938. The pub is open to this day.

3. FRANCIS CROZIER

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier came from a well-to-do family in Banbridge, County Down. He was born in 1796, joined the navy at 13 and served with great distinction for almost 40 years.

Crozier was master seaman and involved with the three major discoveries of the 19th century — navigating the North West Passage, finding the North Pole and mapping the Antarctic. He sailed on six expeditions but alone among the great naval explorers of the age — Franklin, Ross, Parry, etc — Crozier never received a knighthood.

Crozier assumed command of the disastrous Franklin expedition to North West Passage in 1847 and led the desperate battle to escape from the ice. None of the 129 men survived, though Canadian archaeologists have recently discovered the wreckage of one ship which may provide vital clues to the causes of the disaster.

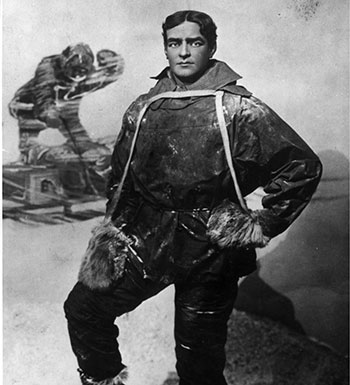

Pictured in 1908 is Irish Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Pictured in 1908 is Irish Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)4. SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON

Ernest Shackleton, born near Athy, County Kildare in 1874, dreamt of being an explorer as a child and subsequently lived the dream on four remarkable voyages to the Antarctic.

He sailed with Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition in 1901 and returned in 1909 to march within 97 miles of the South Pole. His greatest venture, the Endurance expedition, took place exactly 100 years ago when his ship was crushed by the ice and Shackleton led 28 men to bleak refuge on the hostile Elephant Island. Leaving 22 men on the island, he sailed an open boat to South Georgia and eventually rescued the castaways.

Shackleton was an outstanding leader who made one final voyage to the Antarctic and died in South Georgia in 1922, aged 47. On being told of her husband’s death, his wife Emily ordered that he be buried in the south — “where he was happiest”.

5. PATRICK KEOHANE

Patrick Keohane was a man of the sea, brought up near Barry’s Point on the Seven Heads Peninsula in Cork. His father was coxswain of the Courtmacsherry lifeboat, among the first vessels to reached the torpedoed Lusitania in 1915.

Keohane entered the navy at 16 joined Scott’s ill-fated expedition to the South Pole. He marched to within 350 miles of the Pole in 1911 and was a member of the party which buried Scott a year later.

Keohane was married into a Cork coastguard family and fled to England during the War of Independence. He served in two World Wars and lived long enough to act as an adviser to makers of the film, Scott of the Antarctic in 1948.

6. ROBERT FORDE

Robert Forde sprang from the hills of West Cork near Kilmurry and was almost certainly related to the legendary car maker, Henry Ford whose family came from the same area. He was born in 1875 and joined the navy in 1891.

Forde joined Scott’s South Pole expedition in 1910 but was invalided home after suffering a severely frostbitten hand during a sledging trek when temperatures plunged to -73° F (-58° C). He was multi-skilled and left behind a makeshift granite shelter which is now protected as a site of historic interest.

Forde, a protestant, returned to Cobh during the post-independence upheavals and kept silent about his service on the Scott expedition. He lived until 1959, the last surviving member of Scott’s three men from Munster — Crean, Keohane and Forde. He was still wearing a glove to protect his hand from the effects of frostbite half a century before.

Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship SS Nimrod in the Antarctic pack ice. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship SS Nimrod in the Antarctic pack ice. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)7 & 8. TIM & MORTIMER McCARTHY

Mortimer and Tim McCarthy, one of only two pairs of brothers to serve with Scott and Shackleton, were raised near the waterways of Kinsale in Co. Cork. Both went to sea at an early age and Mortimer worked as a seaman for over 70 years.

Mortimer lied about his age and joined at 12 before signing up for Scott’s Terra Nova expedition to the Antarctic in 1910. He made three round-trips to the Antarctic on the ship and was still working on ships in his 80s. Mortimer made a nostalgic trip to the Antarctic in 1963 at the age of 81 and died in a tragic fire in 1967, aged 85.

Tim McCarthy was a merchant seaman with a flair for handling small boats learned in Kinsale. He joined Shackleton’s Endurance expedition in 1914 and was an important member of the James Caird on the open boat journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia. Tim went back to the sea and his ship was torpedoed with the loss of all hands in March 1917. Tim was 28 and his brother, Mortimer collected his Polar Medal.

Michael Smith is an authority on the history of polar exploration. His books include: An Unsung Hero — Tom Crean, Great Endeavour — Ireland’s Antarctic Explorers and Shackleton — By Endurance We Conquer