SAS: Rogue Heroes – a historical drama depicting the fascinating true story of how the famed Special Air Service was formed – is now available to stream on BBC iPlayer. The six-part series has been created by Peaky Blinders writer Steven Knight, and is based on the bestselling book of the same name by historian Ben Macintyre.

Tune in, and you’ll meet Paddy Mayne, one of the founding members of the SAS (played by Skins star Jack O’Connell), a rogue hero whose history is still mired in controversy.

THE Irishman Robert Blair “Paddy” Mayne must rank among the most courageous and significant heroes of the Second World War.

Yet his name is little known outside of the realm of military history buffs, and perhaps, thanks to a pending BBC drama, also Tom Hardy fans.

Born in 1915 and a native of Newtownards, the shy, unassuming demeanour of this young Northern Irishman belied the fact that he was something of a sporting polymath; already a formidable golfer, boxing champion and rugby player, capped for Ireland, by the age of 18.

Competing in the 1938 Lions Tour of South Africa, the then 23-year-old Mayne could not have known that but a year later he, along with much of the British Isles – the team he was representing, would be off to war, much of it fought at the other end of the African continent, in the Sahara Desert.

Like countless others in the murky days of 1939, when the folly of appeasement was becoming plain under the gathering storm of war, Mayne enlisted, opting to join the 5th light Anti-Aircraft Battery.

Frustrated by the stasis and anti-climax of the initial stages of the war from 1939 to early 1940, sometimes dubbed the ‘phoney war’, Mayne, along with some friends and his brother, Douglas, transferred units; taking him to the Royal Ulster Rifles (RUR) and Douglas to the RAF.

Relief from the nervous tedium of waiting for war would not come for some time after Mayne’s transfer.

Though perhaps offering some consolation, the RUR is where he met Eoin McGonigal, a southern Irishman living in county Tyrone, with whom he forged one of the closest friendships of his life.

It was to be the underhanded invasion of Denmark and Norway by Hitler’s Wehrmacht, and the stunning Blitzkrieg of German Panzers through the hitherto thought impenetrable forest fortress, the French Ardennes, and later through the streets of Paris in the spring of 1940, that would get the war wheels churning and set Mayne’s fate on a different course.

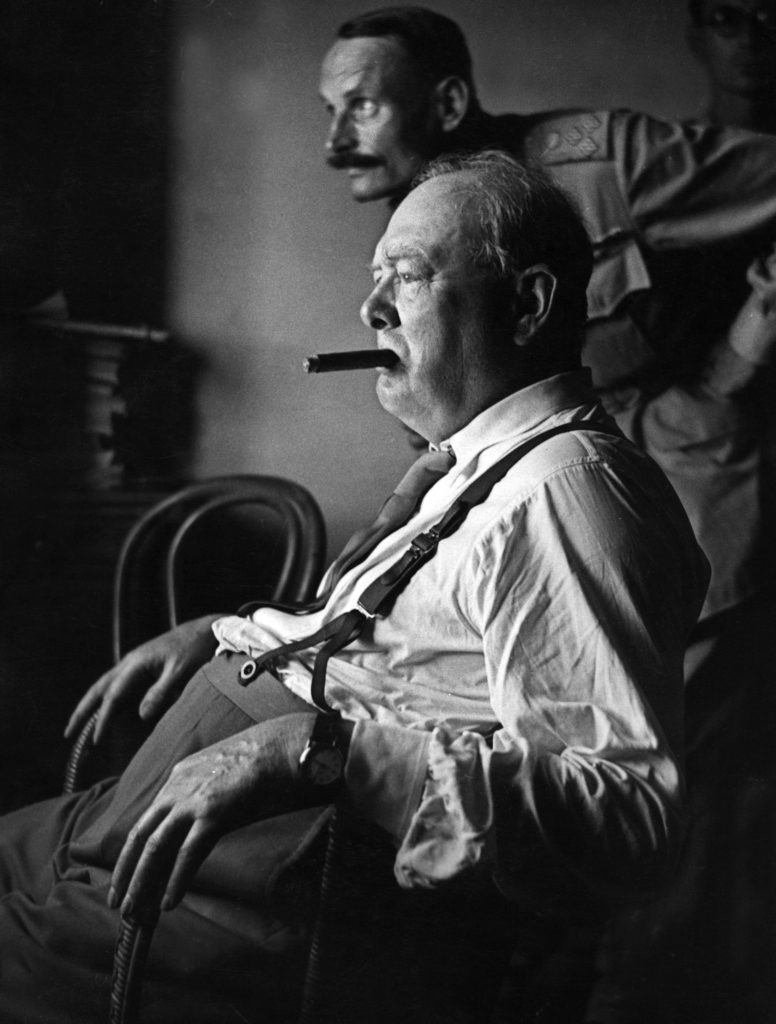

Change was afoot in London also, where the summoning to Buckingham palace of the bullish, soon-to-be septuagenarian parliamentary outcast, Winston Churchill, fundamentally altered Britain’s approach to the war.

The appeasement faction was silenced by a new logic, pithily expressed by the new Prime Minister: “You cannot reason with a tiger when your head is in its mouth.”

The change in leadership had profound strategic significance.

Paddy Mayne was one of the first recruits to British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill's new elite unit within the British Expeditionary Force

Paddy Mayne was one of the first recruits to British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill's new elite unit within the British Expeditionary ForceBeing an early champion of the tank and the aeroplane in the First World War, Churchill was uniquely positioned to appreciate the significance of these, among other military developments, in the coming war.

Gone were the days of static trench warfare and the gruesome, shell and flesh grinding stalemates of that conflict.

Specifically, the need for an elite unit to act in ways that were out of the question for conventional forces – spearheading attacks, as well as conducting sabotage and espionage behind enemy lines – was becoming apparent.

Orders were thus handed down – bypassing a sclerotic military establishment – and upon its creation, some of the first recruits to this new elite unit within the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) would be Paddy Mayne and Eoin McGonigal – the unit would later be called the Special Air Service or SAS.

The SAS, or L Detachment as it was known then, still in its infancy by the summer of 1941, was preparing for its first mission.

Training ranged from the somewhat farcical – jumping from jeeps cruising at 30 miles an hour to simulate parachute landings – to map-reading and desert navigation; skills that could mean the difference between life or death when operating in the million-square-mile expanse of the Libyan desert; an area approximately the size of India.

This experimental training was put to the test in the worst possible way on the November 16, 1941 when the unit, at this point full of bright-eyed military misfits, embarked on operation Squatter, and what would be its first tragedy.

Despite ominous stormy weather forecasts, David Stirling, the unit’s headstrong leader decided to go ahead with a parachuting mission behind enemy lines.

Forming several groupings, one each led by Mayne, McGonigal, Stirling, and two others, the men had planned to regroup at a rendezvous point after sabotaging five German and Italian airfields.

While Mayne had an unusually smooth landing, Stirling was knocked unconscious and McGonigal broke his neck on impact.

Of those that cleared the landing, many were lost in the disarray that ensued from being scattered, almost at random, among the desolate, wind-stricken, and by now pitch-black dunes of the Sahara Desert.

Despite the gale force winds and flood that accompanied the storm, Mayne insisted on carrying out the mission, only to be stumped by pencil charges on the detonators, which, soaked through by the rain, rendered their explosives useless.

After some persuasion that grenades were an unlikely substitute against Luftwaffe planes, Mayne reluctantly called it off.

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Blair "Paddy" Mayne was a Northern Irish soldier, solicitor, rugby union international, amateur boxer, polar explorer and co-founder of the SAS.

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Blair "Paddy" Mayne was a Northern Irish soldier, solicitor, rugby union international, amateur boxer, polar explorer and co-founder of the SAS.The losses from operation Squatter were staggering; of the fifty-five men that accompanied the unit’s maiden mission, only 21 returned – the rest had either been captured, if they were lucky, or killed.

Among the latter was Eoin McGonigal, Mayne’s best friend and possibly his only confidante.

The exact nature of their relationship is unknown and to some extent, owing to the paucity of documents, unknowable.

Left thus to the popular imagination, much hearsay and half-baked speculation have filled in for fact since the Irishman’s unfortunate demise in 1955.

Like other enigmatic – often broody and bibulous – characters subjected to the prejudices (and hypocrisies) of the era, Mayne was suspected of being a closet homosexual.

His shyness – especially around women – and his propensity for bouts of drunken violence have fed into the myth of the repressed homosexual.

Though a compelling tale, Hamish Ross, Mayne’s latest and most thorough biographer is sceptical of these claims, arguing instead that Mayne was a deeply private and misunderstood person.

What is less controversial is that Mayne was very aggrieved by the loss of his friend, but as was characteristic of all the men in L Detachment, he dealt with his grief with extreme stoicism.

Only once he was given leave, when his comrades flocked to the hostelries of Cairo, did Mayne journey to the area where McGonigal was killed.

He wrote to McGonigal’s mother afterwards, informing her of his trip, but told no one else about this quiet, dignified tribute to his fallen friend.

Such humility was characteristic of Mayne, who during his sporting days was praised for his “unfailing modesty and charm of manner”.

The soft-spoken desert warrior was not without his demons, though, and could act out in unsettling ways.

One such episode occurred on December 14, 1942 on a mild North African night, as detailed in the book SAS Rogue Heroes, by historian Ben Macintyre.

After slipping onto Tamet airfield, in a single file formation that mimicked the planes they were about to demolish, Mayne and his unit delayed planting the bombs.

A long hut stood at the edge of the field where, diverting their attention, a light glimmered underneath the door, and “sounds of merriment” and a “mixture of German and Italian voices” came from within, writes Macintyre.

With weapons drawn and flanked by two comrades, Mayne kicked open the door to find a smoke-filled room, lined with confused and inebriated enemy officers whose “merriment” was slowly subsiding into an uneasy silence.

Rarely one for self-embellishment, Mayne, according to Macintyre, broke the silence with the unmistakably Anglophonic (and even Bond-like) greeting: “good evening”.

By adding an immediate and terrifying clarity to what must have been a baffling confrontation, these three syllables sent the room of thirty into “pandemonium”.

Mayne and his men opened fire and the scarpering officers put up what little resistance they could.

This episode, as intimate as it was gruesome, “veered away from sabotage and close to assassination”, the author maintains, and it has dogged Mayne’s reputation ever since.

Macintyre concedes that “killing highly trained pilots was, arguably, an even more effective way of crippling enemy airpower than destroying the planes themselves”.

Though he suggests that something darker than pure pragmatism may have been animating the blood-sodden Irishman that night.

Perhaps the recent death of his friend, or the horrific and slow burning toll that war takes on the psyche meant that Mayne, “faced with the opportunity to kill at close quarters, had been unable to stop himself”.

Mayne, as part of Churchill's SAS, was described as "ruthless" in battle

Mayne, as part of Churchill's SAS, was described as "ruthless" in battleWhatever the truth may be, Mayne’s actions conformed to the worst stereotypes of the new unit – as thugs – to which many in military headquarters still subscribed.

He was later rebuked by Stirling, who said that while “it was necessary to be ruthless…Paddy overstepped the mark”.

Mayne’s ability not only to contend with but to instil fear in his enemies, helped him mould the SAS into what, by end of the war, was a world-class and indispensable fighting force.

A brief tally of the damage that he inflicted on the Nazi war machine shows why: Mayne singlehandedly destroyed over one hundred aeroplanes and caused his axis antagonists untold logistical and psychological grief during his time in L Detachment.

By demolishing 47 planes in one sitting, moreover, he may have even surpassed the record of Britain’s top flying ace.

A blend of traits went into making this man, so revered in SAS mythology, who he was.

These include an unshakable judge of character, audacity by the boatload, preternatural strength, and grit.

But more controversially, there is little doubt that his vast capacity for sheer violence had a devastating toll on the enemy and must therefore be counted against Paddy’s worst excesses.

When David Stirling was captured in January 1943, command of the unit fell to Mayne until the end of the war in September 1945.

Though the job entailed a greater logistical focus, and meant less time spent in the field, he nonetheless fought bravely and with distinction up to the end.

Like the Celtic warriors of old, Paddy had a penchant for listening to music and poetry during war, and so he strapped a record player to his leg while parachuting into occupied France.

This enabled him to blast the ballads of Percy French from his jeep as he pierced through the remnants of the German army, clearing the way for the combined allied forces to break through at various points on the long, drawn-out march to Berlin.

Despite his acts of bravery, Mayne was overlooked for a Victoria Cross medal

Despite his acts of bravery, Mayne was overlooked for a Victoria Cross medalIt was during this period that Mayne displayed his most remarkable act of “brilliant military leadership and cool calculating courage”, according to Hugh Halliday, in his 2006 book, Valour Reconsidered: Inquiries Into the Victoria Cross and Other Awards for Extreme Bravery, when he “drove the enemy from a strongly held key village thereby breaking the crust of the enemy defences” throughout an entire sector – considerably speeding up the allied advance.

This act of bravery led to Mayne being put forward for a Victoria Cross, the highest honour the British State can bestow.

But the award was later downgraded (as was standard practice at the time) to a Distinction of Service Award (DSO).

The decision has courted much controversy, and even caused a baffled King George VI to enquire as to why the Cross had “so strangely eluded him” at the time.

It remains an open question.

While Mayne certainly grated some of his superiors in the military establishment, internal military politics alone cannot explain the reluctance to award the Cross today.

After the war, Mayne did a stint with the British Antarctic Survey in the Falkland Islands that was cut short by crippling back pain from his service days – which, ironically, did little to prepare him for a quiet and comparably dull civilian life, working as a solicitor in Newtownards.

Returning home from a night spent drinking with a friend, Mayne, the man who had driven jeeps through warzones on several continents, crashed his car and was pronounced dead in the early hours of December 14, 1955.

He can therefore only be awarded, if at all, posthumously.

But “perhaps Blair Mayne is destined to go down in history as the bravest man never to have been awarded the VC”, as Peter Forbes, an expert on Mayne’s life, told the military historian Lord Ashcroft.

Originally published 24 February 2021.