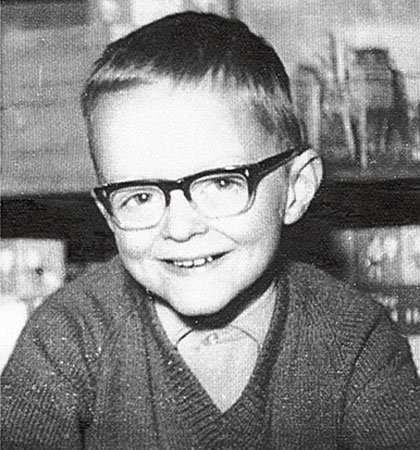

TONY DOHERTY was just nine years old when his father Patsy was shot dead by British soldiers on Bloody Sunday.

The Derry man went on to help set up a campaign, which almost 20 years later, led to the exoneration in 2010 of his father’s name and all those killed and wounded on Bloody Sunday.

There was also a public apology from British Prime Minister David Cameron.

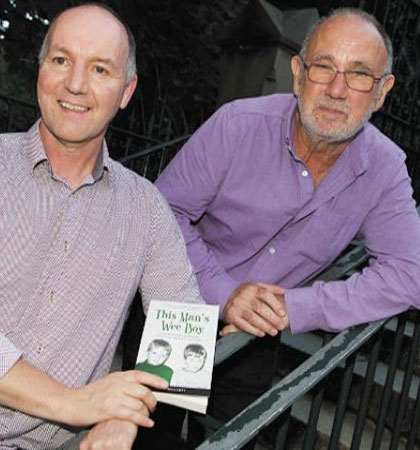

Doherty has now published a book about growing up in a working-class family during the Troubles.

This Man’s Wee Boy: a childhood memoir of peace and trouble in Derry is set in a city on the verge of civil war.

The book deals directly with his father’s death and funeral – something the author found particularly difficult.

“I experience those memories exactly the same today as I did when they happened,” he says.

“I normally choose not to visit that site though as it can’t be good for you. This was the only part of the book that I didn’t enjoy but felt it had to be done.

“I remember I was due to write the first draft of the final chapter in mid to late December 2014 and I told my other half this and she turned to me and said ‘You’re not writing about it in the mouth of Christmas Tony, sure you’re not?’

“It was more of a command than a statement. I waited until early in the New Year and wrote it in the bleak early mornings of January 2015.”

He was by all accounts a very loveable man with a heap of friends and his loss had a huge impact on me, us as a family and his friends

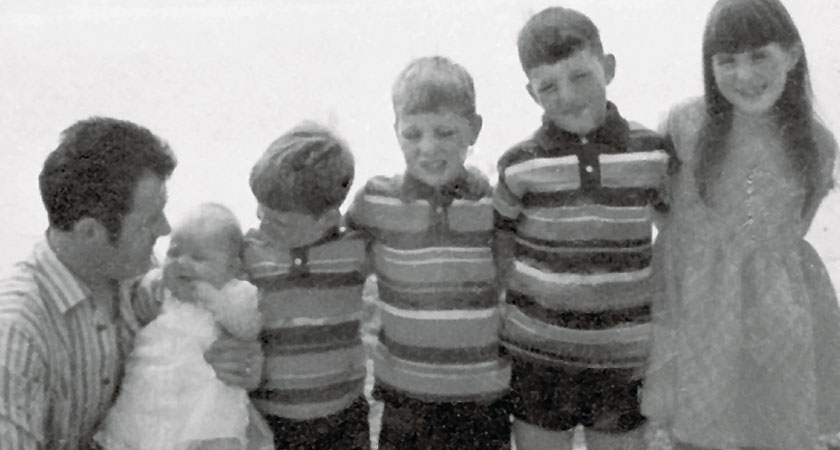

Doherty describes life for his family back then as difficult.

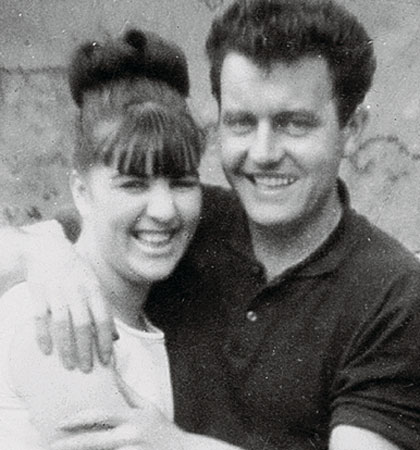

“Me da was away working in England for most of the early to mid-60s,” he says. “There was no work here by all accounts.

“He wrote to me ma and she wrote back and he called her to the phone box on Foyle Road every Tuesday night at seven o’clock.

“I have no memory of him being away at all. My memory starts about 1967 and I think he was back then for good. And yes, I did love him.

"He was by all accounts a very loveable man with a heap of friends and his loss had a huge impact on me, us as a family and his friends.”

Doherty says he is confident he has represented his father well in the book.

“Curses and warts and all as they say,” he jokes.

Most of what I have written are brief clips of ordinary, everyday experiences

Now working as the Regional Coordinator of the Healthy Living Centre Alliance, where he is involved in reform of the health service, his book is set against a background of growing tensions between Derry’s residents, the B-Specials and the British Army.

Doherty paints a picture of the local characters on his street, as well as the joys and tribulations of being a child until one cold January afternoon when the conflict changes his and his family’s life forever.

Asked why he felt now was the time to write his book, he cites a mixture of intent and coincidence.

“In 2011 I found myself with time in my hands and began to read more,” he says.

“I keep [Seamus Dean's novel] Reading in the Dark handy on the bookshelf and flick through it every now and then, but I read it for the second or third time.

“There is a reference in the book to a wee boy being knocked over and killed by a truck on Westland Street and I remember it striking me as a bit weird that I knew Damien Harkin from my class and that he too was killed by a British Army 3-Tonner practically right in the same spot in 1971.

“This cross-reference stuck in my head since then.”

A conversation at the kitchen table in 2013 with his wife Stephanie about growing up in the Bog and Brandywell in the early '70s sealed the deal in the author’s mind.

A few unsuccessful attempts at writing in 2013 and 2014, followed by a meeting with novelist Dave Duggan at Ulster University and there was no going back.

“That two-hour cup of tea in the canteen was a real light bulb experience for me and I went away with a far clearer view of the possible,” he says.

“I then proceeded to write first about Damien Harkin, got it published in the Derry Journal in July 2014 and from there began to write about my earlier childhood right up to 1972. That’s how it happened.”

But the task to accurately remember events was not without its challenges.

“Most people don’t reckon I have a good memory,” he laughs.

“Most of what I have written are brief clips of ordinary, everyday experiences. I was aided in no small measure by talking to my older sister Karen and my wee brother Paul, or Dorts as he’s known.

“Both of them were really valuable. Karen tells stories almost exactly like me ma; the same intonation and movements.

“She was great on describing our house better than I remembered, most of the Elvis story was cleared by her, as well as helping me with the day of my father’s death. Talk about difficult conversations.”

“The words did flow – sometimes,” he adds.

“Other times they didn’t. I reckoned the only time I’d get head’s peace to write would be in the quiet of the mornings, so I began rising earlier than normal, usually about 5.45 so I could grab a few hours at the kitchen table.

“Once you take on a serious writing project, especially if it’s about yourself, I found myself becoming immersed in it and, if I saw someone from our street down the town or out at night I’d usually make a bee-line to them and ask them this or that about growing up and all.

“Usually the best ideas came to me when I was in bed, so I kept a wee note-book and pen handy to the bed to scribble down the odd word or sentence.”

When the soldiers came to the Brandywell it too was an exciting time as this had never happened before, they were English like most of my favourite footballers, they had guns like the soldiers in war films and they had money as well!

Doherty describes growing up in the Brandywell in the '60s and '70s as a magical time.

“Playing on the Banking and going out the Line to fish and playing football in the street are all golden memories, not just for me but for the large groups of boys and girls who we knocked about with,” he says.

“When the soldiers came to the Brandywell it too was an exciting time as this had never happened before, they were English like most of my favourite footballers, they had guns like the soldiers in war films and they had money as well! What else do you want?

“Then when the IRA showed up some time later it was even more exciting as here were men from our streets who spoke like us running up and down Hamilton Street with long wooden rifles.

“In a very real way we incorporated the burgeoning conflict into our play. Of course, after Damien Harkin was killed and then other events described in the book happened, things took a turn for the worst.”

The book, Doherty admits, has given him a chance to get to know his father again.

“I reckon I know him better now than I did before 1972,” he says. “This is because I had to take myself back to how he was – his smile, the smell of Park Drive, Carling Black Label bottles and his work boots – and rediscovered him through the brief chats we had or this or that.

“He was a kind and very thoughtful father and he always took time with us – that’s what renewed memories tell me.”

As for a follow-up?

“I have been thinking and scribbling and have worked up a few chapters covering the 1972 and '73 period,” he says.

“I’m beginning to show them to people and the initial feedback has been very promising. I’ll only keep writing if I think people will enjoy it – the other aspects of my early to teenage life.

“I’m due shortly to speak to Mary Feehan, the Commissioning Editor of Mercier to suss her out. So we’ll see.”

This Man’s Wee Boy is published by Mercier Press, out now on Amazon. ISBN: 978-1781174586