OVER 30 years ago former Beirut hostage Brian Keenan was kidnapped by Islamic extremists and held for four-and-a-half years. He speaks to SIOBHÁN BREATNACH about surviving the odds and finding peace of mind in surprising places

THREE decades on from an inconceivable four-and-a-half year kidnapping ordeal that made him a household name, former Beirut hostage Brian Keenan is feeling philosophical about life.

Over 30 years ago , on April 11, 1986, the Belfast native’s life was changed in the most unimaginable way when he was captured by terror group Islamic Jihad in Lebanon.

As one of over a hundred people taken hostage in the Middle East in the 1980s and early 90s, it was a crisis that received international attention.

With conflict still raging in the region today, his story is as relevant now than ever.

"About six or eight months ago a woman came over to me,” Keenan says. "I was in Tesco when she came over and said ‘I just wanted to say I’ve seen you here a few times but I didn’t want to come over, but I thought I’d better come over today and say welcome home'."

He laughs. "That’s what people remember, they remember the hostage and that’s always reinforced to them because of what’s happening in the Middle East, people getting executed and murdered. It’s always recent to them."

Brian Keenan pictured at a press conference in Dublin Airport in August 1990 following his release Photo: RollingNews.ie

Brian Keenan pictured at a press conference in Dublin Airport in August 1990 following his release Photo: RollingNews.ieHis predictions for what lies ahead in countries such as Syria, Egypt, Turkey, offer little comfort.

"I think we’re in for 30 years of this," he says. "My own view is that this is not going to be fixed with peace agreements.

"The map of the Middle East is going to be redrawn again and I hope that those who draw it are more careful and considerate with that they’re doing. Some people have vested interest in creating conflict.

"I think that ISIS, or whatever it calls itself, will die of its own poison. A nation state that doesn’t nurture feelings of humanity, of love and compassion, will wither away of its own poison. Unfortunately it will create a wasteland before that happens."

But life today for the writer and broadcaster, living happily with his family in Dublin, couldn’t be further from the years he spent in a concrete cell - often in solitary confinement, blind-folded, interrogated, chained half-naked and beaten, at the mercurial whim of his captors.

It was an experience he describes as being dragged through kicking and screaming.

"You didn’t know if it was night or day. In the end, after a long time, I kind of gave up and said right if I’m going to go mad here, I’m going to go mad," he says. "I’m going to choose it, that’s what I did, I let it go.

"You play the pied piper to your own insanity. You’re not fighting it anymore. You’re running ahead of it. In some way you are stronger than it by not fighting it. Then what’s fearful becomes fantastic."

Having left Belfast in 1985 disenchanted by its troubled streets, Keenan arrived in Beruit to take up a teaching position in the city’s American University.

The intention was to stay in Lebanon for a year or two before going to Thailand, his urge to travel being fueled by a desire to find something greater than himself.

"When I left I had no intentions of coming back to Ireland, it wasn’t in the long view for me," he says. “I’ve been a traveller all my life. But if I went to the bottom of the street I could get lost.

"But I learned that what I was looking for wasn’t going to be found in a psychical place. The landscape I wanted to be was me, was in me.

"We all have a route map laid down in our central nervous system and we all have to follow that one way or the other, either blindly or willingly," he adds.

"You have to come back from your point of departure to understand where you’ve been and how meaningful it is."

And Ireland became just that following his emotional release in August 1990, when he sought refuge in Westport, Co. Mayo.

He stayed for three years.

"I was travelling around looking for a place to live but I was also looking for a safe house,” he says. "I came home to get away from journalists and TV.

"A lot of curious things happened when I arrived in Mayo, as if there was a kind of invisible authority, an invisible voice saying stay.

"I was there by myself, that’s what I wanted," he adds. "When you come out of those situations it’s very easy to be led by people who are well-intentioned.

"But they could easily lead you to places you don’t want to be and you’ve got to find yourself back again. Mayo was very inviting. It’s a kind of wondrous landscape.”

Now 65, Keenan’s life is grounded by his family – namely his wife and two teenage sons, 18 and 16.

"In my case true north is my wife Audrey and my sons Jack and Cal. They give me my latitude and longitude in life. I never get lost wherever I go because I have my longitude and latitude with me and my true north fixed. I don’t need to travel so much anymore."

But that didn’t stop him from spending six months in the Alaskan wilderness, a trip inspired by Jack London’s book Call of the Wild, which he read as an eight-year-old boy.

"He says in the far north he found his perspective, I was intrigued by that," Keenan says of the adventure which was documented in his 2005 book Four-Quarters of Light: An Alaskan Journey.

Brian Keenan following his release in 1990 with his sisters Brenda Gillham and Elaine Spence who has campaigned for his freedom Photo: RollingNews.ie

Brian Keenan following his release in 1990 with his sisters Brenda Gillham and Elaine Spence who has campaigned for his freedom Photo: RollingNews.ieThough now living in the Irish capital, Belfast is a place he still regularly visits.

It is home to his two sisters Elaine and Brenda, who campaigned tirelessly to secure his release at a time when many western governments abided by a ‘no negotiation’ policy.

He describes having an impatience with the Northern Irish city he once called home over "its crippled capacity to remake itself".

"Alaska opens you up to an immensity with which, again not be to disparaging, but the Troubles in some places are like a nice ruin, almost as if it wants someone to fix it instead of fixing itself."

But the draw of friends and family, it would seem, overrides any greater irritations surrounding the social politics of the North.

"There’s a time in our lives that we find out what is valuable, what is meaningful," he says.

"I suppose like anybody else, time feels more important to me than money or wealth or books or travel or fame, which can feel like a kind of prison and I’ve had enough of that for a lifetime."

Keenan is not a religious man.

"I leave religion to religious people," he says. "Our capacity to believe is so immense, why should we reduce it down to whatever somebody with a cross or crucifix waves at us.

"Again, I’m not being disparaging, but I think our capacity to believe is greater than the literary that is offered up to us."

So rather than turning to God during those torturous days in captivity, the Irishman found other ways to survive.

"I used to exercise furiously," he says. "You’re thinking about books or movies, you rewrite the movie. But you’re in a conflict situation so no matter what you think you’re doing, in the end it’s going to win.

"I look at all these religions, you have the 12 Commandments or there’s this path, for me it doesn’t work like that.

"You climb up on a ladder and someone takes the ladder from under you and you fall down again. You’ve got to start climbing up again even though you know you’re going to fall down.

“There was no alternative,” he adds. “There was no notice outside my cell door with a release date in it. Two of my friends were executed a few cells up from me, so you had to deal with that.

"I didn’t know if I was going to be shot, I didn’t know what was going to happen to me."

“There was a guard once that said to me as he was drilling that pistol into my temple, he said ‘there is only one life, and we do much’ and I laughed at him because in the lunacy in my mind I had done more than he could do in a million lifetimes.

"Because his lifetime was determined by a government and whatever religious nonsense that had fuelled his imagination.”

Keenan would sing songs by fellow Belfast man Van Morrison during his time in captivity Photo: Stephen Lovekin/Getty Images)

Keenan would sing songs by fellow Belfast man Van Morrison during his time in captivity Photo: Stephen Lovekin/Getty Images)During those long dark days, Keenan promised himself that should he ever taste freedom again, he would buy an old stone cottage in the West of Ireland and write a book.

"I used to plan it in my head, the stones would be this way and the floor that…the promises you make yourself to keep yourself sane, when you’re out and free you have to actually go and do those things, it’s a kind of therapy."

Music also proved part of that therapy, both during and after his captivity.

While appearing on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 1990 to mark his first Christmas as a free man in five years, the songs of James Galway, Joni Mitchell, Paul Brady and traditional Irish composer Seán Ó’Riada were among his chosen catalogue.

And it was to the tune of fellow Belfast man Van Morrison that Keenan would sing to his cell-mate, British journalist John McCarthy, who in turn shared his best Mick Jagger impersonations.

"I wanted to write a book but it wasn’t going to be about my time in Lebanon," he says. "I didn’t think there was a book in it. (There was…the 1991 award-winning autobiography An Evil Cradling, which won the Christopher Ewart-Biggs Memorial Prize among others.)

Brian Keenan and son Jack along with British journalist and fellow hostage John McCarthy at Áras an Uachtaráin with president Mary McAleese in 2000 Photo: RollingNews.ie

Brian Keenan and son Jack along with British journalist and fellow hostage John McCarthy at Áras an Uachtaráin with president Mary McAleese in 2000 Photo: RollingNews.ie"I wanted to write a book about music,” Keenan adds.

In 1996 he published Turlough, a book about 17th century Irish harpist Turlough O’Carolan that he spent two years researching while writer-in-residence at Trinity College Dublin.

"I don’t have a musical bone in my body,” he admits. “But I found myself when I came home, travelling in the car and I would only play classical music.

"I spent a lot of time in art galleries, one of the things I did when I was locked up was I painted pictures in my head and hung them on the walls of my cell, so I had my own little art gallery.

"And I still do walk into art galleries and spend a lot of time there looking and thinking and discovering things."

Fear is a familiar companion for Brian Keenan.

"One of the problems I have, not so much now I’m older but when I was younger, is I was afraid of being afraid. When I went into the fearful aloneness of the Alaskan bush – which was quite a frightening experience – I didn’t expect to be that frightened.

"It was isolation and aloneness in a vast panoramic landscape, not in a six foot by four foot dark cell – one is the flip side of the other."

While there he stayed with Indians and Inuits in Arctic Alaska, meditating with a shaman and chasing spirit bears.

"There’s nothing in which I do not believe," Keenan says. "Seeing spirit bears is alien to where I would have come from, but if you open yourself to receive things, things will come, you just have to not be afraid of it."

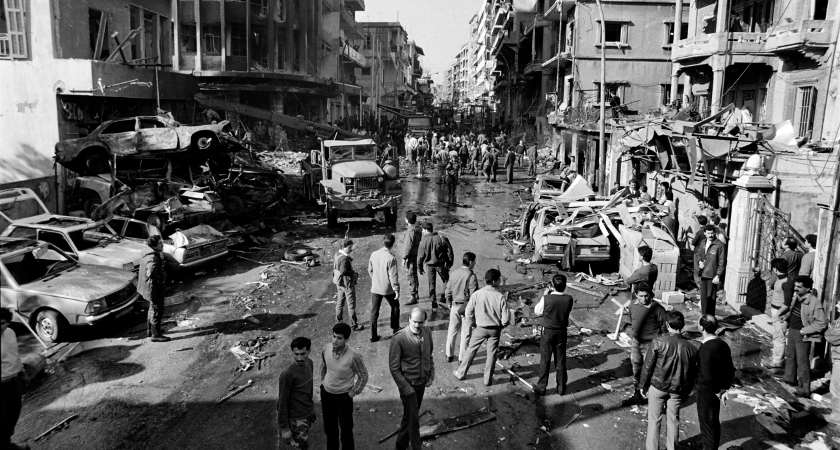

Wreckage after a car bomb explosion in Beirut in January, 1986. Photo: JOSEPH BARRAK/AFP/Getty Images

Wreckage after a car bomb explosion in Beirut in January, 1986. Photo: JOSEPH BARRAK/AFP/Getty ImagesHis first journey back to Lebanon in 2007, one he’s made many times since, brought that all too familiar feeling of fear crashing back.

"Audrey told me I had a lot of disturbing nightmares in the month or two before,” he says. "When I did decide to make that first journey back, because I’d been planning it for a long time in my head, it didn’t kinda bother me."

But as his plane drew closer to the country, he recalls watching the small icon on the in-flight system and thinking: "As it got nearer and nearer to Beirut I thought 'Woah, heck is there a reverse gear on this airplane?'"

He laughs. "But there’s no going back, you can’t."

"I remember on that first journey out reading an article in the New York Times, there just happened to be an interview with a Lebanese writer called Elias Khoury - a very fine writer, writes a bit like Tolstoy.

"He says there are other stories and other narratives that need to be articulated [in the Middle East] but people weren’t picking them up because they were too busy trying to survive.

"And I thought that’s what I’m going to do, that’s what Lebanon owed me – whatever stories I found lying in the street, would be my payback."

Keenan is currently working on a book of short stories set in Beirut, as well as creating a travel piece for the BBC on China.

On his release he famously declared: "I’m going to visit all the countries in the world, eat all the food in the world, drink all the drink in the world, make love, I hope, to all the women in the world…"

Looking back, he says, the reality was somewhat different.

"When I came out I just wanted to get away from people. There was nothing specific I wanted to do, I didn’t desperately want a pint of Guinness - there was none of that."

"I’ve come to an understanding," Keenan says. "I have been given much in life. I look at what I have been given and it’s greater than what’s been taken from me."