Austin Donnelly

Austin DonnellyAUSTIN DONNELLY, vet and author, is passionate about animals and nature. He has a particular fondness for the stories and characters: both human and animal that he encounters in his work. Here he shares with us a series on old Irish animal cures.

Veterinary medicine as we know it, has not always been available in all areas of Ireland. It was the arrival of mandatory Tuberculosis testing of all cattle in the 1950’s that helped bring veterinary services to the smaller towns and villages. Before vets, those people that treated sick animals were termed ‘Cow doctors,’ while herbalists, chemists, clergymen, farriers and locals with cures and charms were often called upon too. Interestingly the term veterinarian roughly translates from Latin as ‘cattle doctor,’ a term perhaps a little out-dated today. Here we look at some of the folk cures used. These can be roughly categorised as either herbal, magico-religious or surgical.

When it comes to herbal remedies, often weeds of cultivation found around the crop fields were used. In Co. Wicklow stockmen used wood sorrel to treat fleas and tick infestations on sheep. A cure for heather blindness (causing a red sore eye) in sheep in Co. Donegal was to roast willow sapling and blow the powder into the affected eye with a straw. There was some primitive science in this cure as willow bark contains salicin, which is a chemical closely related to the drug aspirin and therefore had some pain-relieving properties. Many will recall encountering holly bush cuttings hung high above cattle in barns and byres. This was a remedy for ringworm (a fungal infection of the skin) and preference was for the larger leaves of the male holly bush (the female holly bush has berries.) In some areas this practice was so widespread that the holly bushes became scarce. It is thought that the leaves drop an anti-fungal powder on the cattle as they wilt. The use of holly in this way is still seen on some farms today. Ivy was used in Co. Offaly to treat colic in sheep (a digestive upset) and was widely used throughout Ireland as an appetite stimulant in convalescent cattle and sheep, again, this practice of feeding ivy to sick farm animals is still seen today.

Transference - is a common theme in folk cures. This is where the ‘evil’ that was causing sickness was transferred to a plant or a material and that was thought to resolve the condition. An example of this was the tying of a gut knot in a length of string over an animal that had a suspected obstruction of the intestine. When the knot was untied this was believed to relieve the obstruction. Many stock keepers had concerns that when strangers arrived on their farms, some had the ability to ‘blink’ an animal with an evil eye: that could bring about disease. One way to ward this off was to tie red ribbons on sheep and cattle, especially before trips to the markets. Striking red colours were thought to help keep malevolent faeries away also. There was a cure recorded for a blinked cow and that was to give a drench of mixed garlic and soot. Magico-religious cures often combined prayers. Foul in the foot, is a painful infection between the hooves in cattle, particularly in wet fields in summer. One cure used in many parts of Ireland, was the ‘turning of the sod.’ Although there were variations on how to do this, the affected animal was watched in the field. When the farmer identified an imprint of the bad hoof in the ground, they would then use a pen knife to cut out the sod. In some areas this sod was turned and replaced along with prayers. In Co. Meath the sod was taken to the edge of the field and thrown where possible onto a white thorn bush, with a prayer. Cattle suffering with difficulty standing after calving, were thought to have a ‘worm in the tail.’ Treatment here involved placing garlic cloves under the skin at the tail. With milking cattle receiving this treatment on a morning, it is said the garlic could be tasted in their milk that night. When it comes to early cures for milk fever (where cattle become dangerously low in calcium from overproduction of milk), it was not unusual for a farmer to inflate the cow’s udder with air from a bicycle pump to help stop milk production. There was some science in this, as this allowed the cow to conserve calcium, in those days before our modern calcium supplements!

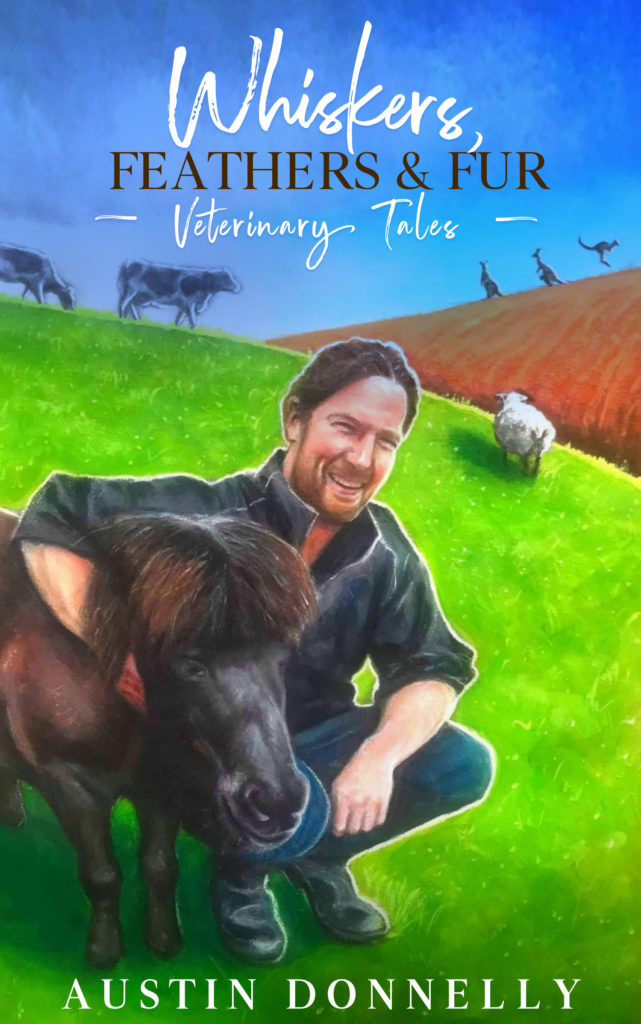

Austin Donnelly is the author of a memoir on his international work as a veterinarian

Whiskers, Feathers & Fur: Veterinary Tales.

All details of how to get a copy are available here (Debut veterinary story collection humor / memoir coming soon!) on Austin's blog