AFTER over three decades in America, my father returned to Ireland to bring me on my first trip home. It was to be his final journey back to the Emerald Isle.

Cheers and applause burst out as the Aer Lingus 707 touches down in the Dublin International Airport on that summer's afternoon in 1961.

My father throws back a shot of whiskey, winks, reaches out and shakes my hand, "I'm home again, Mick. First time after 34 years in America!"

Aunt Ita and Uncle Bertie Carroll, my father's sister and her husband, greeted Pop and me with hugs, tears and laughter and off we go into the golden sunlight to Peacock House, their two-story white-stone home with a little glass greenhouse in the garden in the town of Balbriggan just outside Dublin.

Aunt Ita with smiles and cheer introduces me to my older first cousin, Maurice, and to her daughters Amelia, Rosemary, Eileen and Ita, ages 26 through 16.

I am 22 years old, fresh out of college, and have never seen or spoken to these cousins from the day I was born. And now here they are all shining, pink-cheeked and smiling, reaching out their hands and speaking in soft, lovely Irish accents, "How do you do Michael, and welcome to Ireland."

I feel a surprising instant bond and familiarity with these pretty young women mixed with an intriguing sense of mystery. Louisa May Alcott's Little Women comes to my mind and as I mention this, they all laugh, "Ah, sure, we know that book backward."

We play phonograph records, dance and sing songs by the piano. I am smitten. With all of them. I can't believe I am already plotting my immediate return to Ireland after our three-week visit is over.

The next morning while my father sleeps, Aunt Ita stands over the kitchen table and places breakfast in front of me: "Here's some rashers and bangers and fried eggs for you and toasted brown bread with a nice gob of butter."

She then speaks of my father: "I remember that night the Black and Tans - those terrible British rowdies - came storming into our house in Sligo and roused your father and our brother Pat out of their beds and dragged them down to the road to dig some sort of a ditch.

"They held guns over the lads' heads the whole time. It wasn't too long after when our dear Gus announced he was leaving for America. And so at age 22 in 1928, your father did just that. He left home, got on the boat to New York City and never came back until now."

I had never heard this story before.

That afternoon my cousins take me for a stroll along the nearby strand. Hoping to impress these female beauties, I become the brazen 'yank'. I tell them of my prowess riding waves which I learned from summer days at New York's Rockaway Beach.

I saunter out onto the jetty, strip off my shirt and in my summer shorts leap into the ocean, only to let out a blood-curdling howling roar from the shocking ice cold water of the Irish Sea.

The girls onshore burst into gales of laughter, enjoying the proper comeuppance of their swaggering Yank cousin.

After a few days spent in Dublin, my father and I board the train to Sligo and are greeted at the station by Pop's younger brother Michael, and his two sisters, Kathleen and Maryann.

No sooner had Maryann hugged her brother than she laments: "Ah, God help us, Gus, won't it be a terrible day when ye'll be leaving us again too soon!"

The old home lies near the Holy Well, three miles from Sligo town. My father walks me up a lane and we stand under a sullen Irish sky in the high, dry grass among the fallen stones of the old country farmhouse where he was born and raised.

He is quiet for a long time.

Does he have thoughts of what might have been? Is he glad he left Ireland or does he have regret about not staying here among the fields of his ancestors? He leads me down a deserted dirt road.

"You see that crossroads there, Mick?" he points. "Oh, the life that used to be had there of a Sunday morning after Mass, the boys and the girls, the laughter, the flipping of coins and the gambling, and my own father among them. Those good times - all gone."

As a boy, I remember my father always loved to sing The Lakes of Sligo...

To Holy Well, I bid adieu,

To Hazelwood and Cairns too,

And Toberknock that splendid view,

Which adorns the lakes of Sligo.

I am struck by the beauty of this land - the deep green grass on the sloping hills as we make our way to the Lake Isle of Innisfree made famous by WB Yeats. Here under the great blue Sligo sky and silver clear water, one could indeed feel "peace come dropping slow".

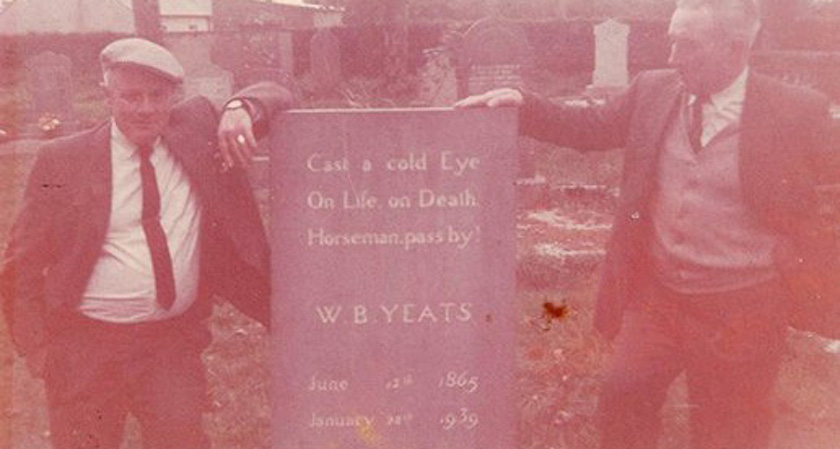

Afterwards, we visit Drumcliff churchyard and I snap a picture of my father by the poet's tombstone: "Cast a cold Eye on Life, on Death, Horseman pass by."

We stop by a thatched cottage of a very old woman, a family friend. As she sits in her rocking chair by the fire she begins to weep as she remembers my father as a boy picking potatoes in her field.

"Never one so full of song as yourself," she whispers. Pop stares into the fire without a word. What is he thinking? Of the swift passage of time? Of parents long gone?

It comes time to travel the 22 miles to visit my mother's home in Co. Leitrim. Mom had returned to Ireland the year before - her first time in 35 years. She helped organise a charter plane to Ireland in our Bronx parish of Sacred Heart in Highbridge and was awarded a free trip for her efforts. She encouraged my father and me to visit the following year.

My mother, Mamie Gallagher, was the oldest of five and at age 16 her parents reluctantly decided she was old enough to leave home. They hoped she would make a better life for herself with her cousins, two nurses in New York City.

"I'll never forget that gray day in 1927 as I stood on the quay in Co. Derry saying goodbye," Mom recounted. "What I remember most was my mother could not stop crying."

Perhaps her mother, Kate, then only in her mid-40s, realised only too well what her departing daughter did not. They would never lay eyes on one another again.

"I was seasick the entire trip across the Atlantic," Mom recalled. Though only 16, she knew her journey carried an important mission: to send money home to bring her brother and sister to join her in America.

Never one to feel self-pity, she did confess once: "I cried myself to sleep every night for that first year."

Like so many thousands of others who left Ireland in those years of the 1920s, the young left their homes, sailed for America, started families of their own and often could not afford to return.

We meet my mother's brother Jim and his wife Margaret and their 10 children who live not far from the town of Bundoran. Uncle Jim points with pride to the land he inherited from his father.

"That field over there lies in Donegal and the field right next to it is in Leitrim," he says with a hearty greeting as if he knew us all his life even though we've only just met for the first time.

My uncle is an accordionist, my father an Irish fiddler, and so after the local pub closes that first night, the pub owner invites a group of us to a back room where the pints keep flowing and Pop and Uncle Jim strike up the music playing jigs and reels, hornpipes and waltzes.

The evening of song and rollicking Irish music and lively banter goes far into the night with Pop on his fiddle and Uncle Jim on his accordion ending with the improbable That's Why the Lady is a Tramp.

That night, and for each night of our visit, my father and I sleep under a thatched roof, under the stars, in the same bedroom where my mother was born 50 years before.

The next day, a Saturday, we make the rounds meeting my mother's cousins. In every home, without fail, I take note of the portrait of newly elected President John F. Kennedy next to a print of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

We visit a cottage of an older cousin, Katie Ruddy, as her elderly husband dozes in his chair in the corner. Katie insists we take a chicken back with us to Uncle Jim's, so out she goes to the yard where her chickens are gamboling about.

As casual as if she were shelling peas, she continues chatting and then spying an especially plump chicken, she grabs hold, traps it between her legs, bends its neck over and with a big knife, slices its throat until the blood comes pouring out.

After letting a good bit of the blood drain, she wraps the now dead chicken in a newspaper and hands it to me saying: "Give this to your Aunt Margaret and Uncle Jim and enjoy a good Sunday dinner tomorrow!"

And sure enough, the next day here's the chicken all brown and crisp and delicious to eat and for a boy like myself brought up on the concrete streets of New York City, it was an amazing sight to behold.

We return to Dublin to catch our flight home. I welcome the chance to visit the four 'Little Women' again who take me off to a local dance one last time. The next morning amidst laughter, tears and farewells, we promise to return to Ireland soon.

Pop, tries to stay stoic, shakes hands all around, but cannot bring himself to utter his final farewell, and I have to propel him out the door so as not to miss our flight.

Arriving in New York, Mom hands me a letter from the U.S. Draft Board: "Greetings, You are ordered to report for your physical..."

My plans to go back to Ireland are now thwarted. For the next three and a half years, I will serve as an officer in the United States Navy.

Mom would live a long life and return to Ireland 15 years later when my brother and his wife bought a grand house in County Westmeath.

Pop died 12 years after our trip and never made it back. They were both very proud Americans but always remained 'Irish to the backbone' till the end.

My parents are long gone now as are my aunts and uncles. But that first trip to Ireland lives on within me. It gave me my first real glimpse into where I came from and to the people who came before me and helped to shape me.

I came to appreciate not only the lives of my mother and father but the lives of the warm-hearted country Irish people who, generation upon generation, have enriched America with so many of their sons and daughters.

* Michael Scanlon, an English lecturer, is the son of Irish emigrants and grew up in the Bronx, New York. He has published a book on his life growing up in Irish America. Rolling Up the Rug: An American Irish Story is available on Amazon.

Article courtesy of Irish Central, originally published 2016.