SINCE his death in 1992, virtuoso painter Francis Bacon’s name has never faded.

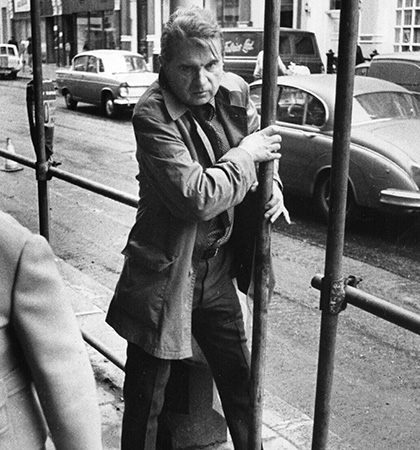

In his own lifetime, he was well-known for the menacing, ghostly half-man, half-who-knows-what figures he painted, to the bad-boy boyfriends, booze-fuelled Soho sessions and romantic relationships, some as dark and twisted as his paintings.

His work, and his reputation have stood the test of time. Art collectors still clamour to Bacon.

Last year, two of his self-portraits, which had been kept from the eyes of the public in a private collection for many years, sold for a combined £30million at Sotheby’s in London.

This May, a new generation in the north of England will get the opportunity to see his works in the flesh when a new exhibition opens at Tate Liverpool.

Francesco Manacorda, artistic director at Tate Liverpool says they are confident Bacon’s name will be a draw. "Bacon is definitely a household name that people recognise. The pictures are visceral and very sensual and effective so I think people will be compelled to see the show.”

Margarita Cappock, head of collections at Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane and author of the book, Francis Bacon’s Studio, says that Bacon’s longevity comes down to the work he produced.

“Because of the quality of the work he hasn’t fallen out of favour in any way, there’s a heightened realisation with younger scholars coming up that what Bacon was doing was quite unique. He was a unique individual, a towering figure of British figurative painting in the 20th century and he’s retained that reputation”, she explains.

Unique is the right word.

Born in a nursing home at 63 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin on October 28, 1909, Bacon was the second of five children. His well-to-do parents were both English.

They first settled in Cannycourt House near the Curragh, Co. Kildare, where Bacon’s father Anthony Edward ‘Eddy’ Mortimer Bacon, wanted to work breeding and training horses.

Home life was no bed of roses for young Francis Bacon. His father was cold and argumentative, his mother wrapped up with herself.

In 1926, Bacon’s father caught him dressing up in his mother’s clothes, kicked him out and he set off on his own path.

However, he didn’t start to paint right away. In the late 1920s, he moved around between France and Germany and then settled in London where he started off as a furniture and interior designer. “He was self-taught, he didn’t go to art college so that immediately made him a bit different”, says Margarita Cappock.

In fact, Bacon was something of an accidental artist. He saw an exhibition of drawings by Picasso in the summer of 1927 and it affected him deeply, firing his imagination. Soon afterwards, he started to draw and paint images of his own.

Major success came in his 40s and 50s when he was producing the large-scale paintings he is best known for.

Around 1944, he finished the painting that made his name. Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (which lives in Tate London collection but will form part of the new Liverpool exhibition) is in triptych format, a form normally associated with religious art. “He was a complete atheist, but he made that form his own”, says Cappock.

Cappock calls the piece his most iconic. Hung in London just after the end of the Second World War, it caused a strong reaction. She describes it as “almost cinematic the way the eye can move between the three. The slightly menacing and horrific nature of the figures that aren’t human… It touched a raw nerve coming at the end of the War to see these biomorphic figures with the bare teeth and bandaged eyes.”

Bacon was master at portraiture too. “What really strikes people is the ability to capture the essence of a personality. Not an easy thing to do,” explains Cappock. Unusually, he didn’t paint his portraits from life, preferring to work from photographs alone in his studio.

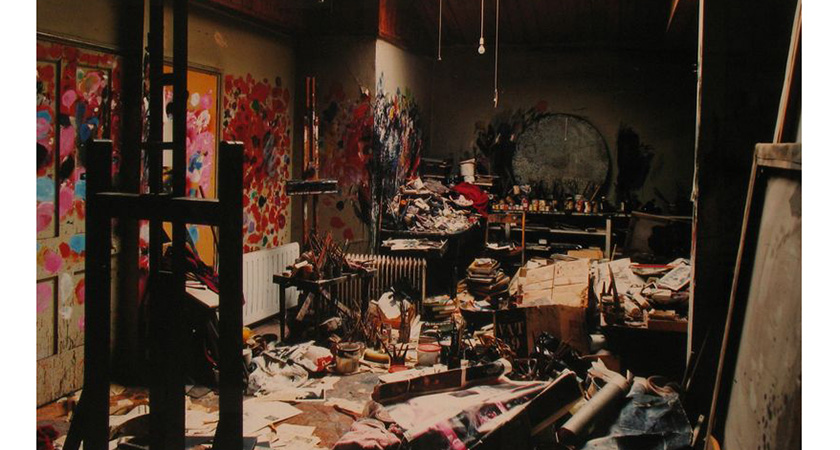

That studio was presented to the Hugh Lane gallery in 1998.

Moved “lock, stock and barrel” from Bacon’s South Kensington digs and reconstructed down to the last tube of paint in Dublin. It opened in 2001, and Cappock says those who visit are still intrigued to see an artist’s studio inside a gallery, with over 7,500 items packed into it – Bacon’s books, photographs, materials, and his easel, which was left with his last unfinished work sitting on it.

While critics agree that Bacon is one of the most important artists of the 20th century, there have been a few tussles over his nationality.

The Irish claim him as their own, but he is more often referred to as a British artist. Cappock, who has just written a paper on the subject for Yale University is well-placed to weigh in on this irksome issue.

Dublin-born to English parents (who had no ties to Ireland), he spent the first 16 formative years of his life in Ireland, and although an atheist, died in the care of nuns. “There’s an Irish dimension to his work”, argues Cappock. “He was very influenced by what he saw… he used to go around butchers’ shops and look at the meat. Meat is such a motif in his work.”

After the bust up with his father, Bacon apparently said he’d never go back to Ireland after he left, but Cappock knows otherwise.

His sister, now dead, confirmed that he returned to Ireland on holiday. In 1965 there was an exhibition of his work in the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin but on that occasion Bacon didn’t return, saying it would be “too much fuss”.

Francesco Manacorda, Artistic Director at Tate Liverpool says the fact that Liverpool is so connected with Ireland should help draw crowds to see Bacon’s work. The show has been planned for years, a partnership from the beginning with the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (where the show will travel to next from 7 October 2016 – 8 January 2017). It’s been a laborious process, requesting 30 paintings, rarely seen drawings and documents from as far as the US and transporting fragile pieces has required persuasion and negotiation but they are nearing the end.

To someone who has never seen the work before, Manacorda and Cappock agree that you need to see Bacon’s work in the flesh. “You need to see them for real, the size, the materiality, the gesture of painting, the material he uses, it needs to be experienced in person. There’s a whole sort of ritual around it, the ceremony. All the paintings are under glass by instruction of Bacon himself and framed with golden frames — if you see this painting in a catalogue or online it’s not the same”, says Manacorda.

“Look closely at the way he manipulates the paint on the canvas and the beauty of the works regardless of the subject matter”, says Cappock, or as Manacorda succinctly suggests: “Focus on the sensation, not the thinking.”

Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms, 18 May – 18 September 2016, Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, Liverpool Waterfront, Liverpool, L3 4BB. Information and booking: 0151 702 7400. Visit www.tate.org.uk