FOR HUNDREDS of years, Irish people have played an important role in shaping modern Canada. In fact, the country is now home to the fourth largest Irish diaspora in the world with around 15% of the population claiming some Irish descent.

The story of the Irish in Canada is a tale of two nations, each with its own complex history and competing political interests. It details how the history and culture of one nation came to impact on the other, but it also recognises that the traffic was two-way, because the flow of money and ideas back home changed Ireland forever.

The story begins with adventurous pioneers who were among the first Europeans to travel there. Surprisingly, it also features seasonal migration, and of course, large waves of famine migrants fleeing death and desperation. It plays out in a land colonised by rival powers, where politics and culture were influenced by its European settlers.

Early Irish Migrants

We know the Vikings reached Canada in the eleventh century. Many think they were the first Europeans to do so, but some say an Irishman beat them to it. The story of Saint Brendan’s Voyage hints that he reached Newfoundland in the sixth century. We can’t say for sure whether this account is true. However, we do know that tales of the fabled lands to the west were passed down orally for centuries in Ireland. It seems we always had a bit of the travel bug in us.

So, when Europeans first discovered Canada, it makes sense that Irish people were among the early settlers. In fact, an important anchorage point near Quebec, used since 1689, was called Trou St. Patrice (St. Patrick’s Hole), pointing to an Irish influence even in those early days.

Quebec marriage records show that 130 marriages which took place at the close of the seventeenth century involved Irish people. Strong political and military links between France and Ireland meant that Irish soldiers served in French Canada both during and after colonisation. For instance, from 1755 to 1760, an Irish Brigade in the French Army won several key battles against the British in Canada. The French Army eventually surrendered and returned to France on English ships, but no Irish were among their ranks. They stayed in Canada to avoid the charge of treason against the British crown.

Interestingly, these soldiers and other early Irish settlers in “New France” left their mark in French-Canadian surnames with an Irish twist: Riel derived from O’Reilly, Sylvain from O’Sullivan, and Caissie from Casey.

Newfoundland’s Fishing Industry

Accounts such as these, however, are a mere prequel to the story of the Irish in Canada. The tale really begins with the seasonal migrants who worked in Newfoundland during the establishment of the island’s fishing industry.

After an English expedition claimed New Founde Land for England in 1497, its rich supplies of cod drew fishermen from all over Europe. The Irish were no exception. The earliest record of an Irish ship returning from the island dates from the 1530s, and records from 1608 report that Patrick Brannock, a Waterford mariner, sailed there annually.

In the seventeenth century, English ships bound for far-off lands would call to Waterford for supplies of food. As Newfoundland’s fishing industry developed, English ships no longer called to the port only for food, but for Irish workers to operate the fisheries. These workers would spend the summer in Newfoundland, travelling back to Ireland for the winter.

During the eighteenth century, Newfoundland evolved from a place of seasonal migration into a permanent colony. Census records tell us that half of the 7,500-strong over-wintering population of 1754 were Irish Catholics. By the end of the century, very few migrants were returning home at the end of the season.

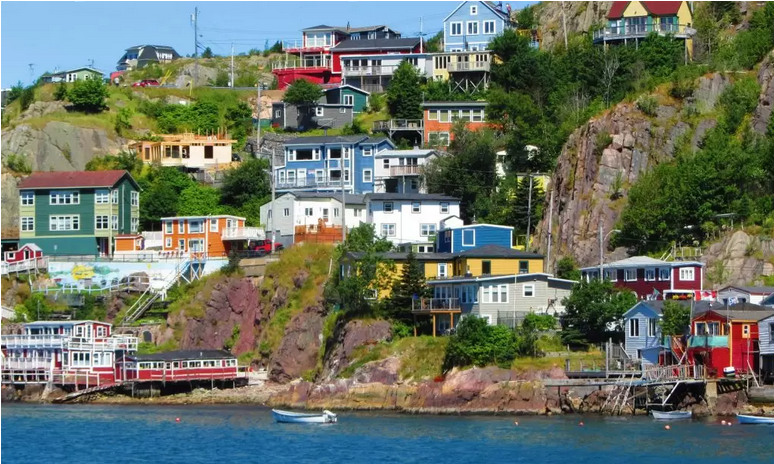

Colourful houses on coast at St Johns, Newfoundland. The traditional colourful houses of St. John’s, Newfoundland. They were brightly painted so fishermen could see them in foggy weather.

Colourful houses on coast at St Johns, Newfoundland. The traditional colourful houses of St. John’s, Newfoundland. They were brightly painted so fishermen could see them in foggy weather.Tensions and Rebellion in Newfoundland

The Irish largely settled in the south-east – separate from the English towns in the north – and retained their own cultural identity. This Irish influence made its way into the island’s spoken language and is still evident today. Words like sleeveen and streel come straight from Ireland and sentences are constructed in the unique Hiberno-English style.

The governing British in Newfoundland labelled Irish workers as papists or rebels. In fact, there was a total ban on Catholic worship until the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. Nevertheless, Pope Pius VI recognised it as an independent ecclesiastical territory in 1784 and sent Fr. James Louis O’Donel to formally establish the Catholic Church on the island.

O’Donel, a man of great energy and authority, pursued a policy of appeasement between his flock and the British residents. The Irish Uprising of 1798 created tensions among the Irish which led to a revolt in 1800 but O’Donel managed to contain the unrest.

Today, Newfoundland is the most Irish place in the world outside of Ireland. It even has an Irish name, Talamh an Éisc (Land of Fish), conferred on it by early Irish settlers. Because of its historical ties with Waterford, most of the Irish population can trace their roots back to Ireland’s south-east. And they still speak with the accents of their ancestors.

Eighteenth Century Emigration

While the discovery of the New World attracted some adventurous types and provided a seasonal income for many more, the modern Irish experience of mass emigration had yet to establish itself. You could be forgiven for thinking emigration began in response to the hardship of the famine; in fact, it began much earlier.

The first people to leave Ireland in large numbers were Presbyterians. Discrimination caused by the Penal Laws coupled with extreme poverty made foreign lands more attractive. Between 1717 and 1776, a quarter of a million Presbyterians left Ulster. Most went to America, but a significant minority went to Canada and established themselves in Ontario where they left a lasting impression on that city’s culture and politics.

Other parts of Canada also attracted these migrants. During the 1760s, a British army officer called Alexander McNutt became involved in the colonisation of Nova Scotia. He advertised in Ulster for “industrious farmers and useful mechanics” to emigrate to British North America (Canada) where they would be given at least 200 acres of land.

McNutt planned on bringing thousands of Ulster migrants to Canada, but he fell foul of British government concerns that moving large numbers of Protestants out of Ireland could damage the status quo. It ordered Nova Scotia’s Governor not to grant land to Irish settlers unless they had lived there for five years. Despite this setback, communities of Ulster Scots with names like Londonderry and New Donegal established themselves in Nova Scotia .

There was also movement of people between Canada and its neighbour. After the British defeat in the American Revolution (1765-1783), many Loyalist refugees made their way to Canada. An indeterminate number of Irish people were among these numbers. This migration worked both ways, however; many Irish migrants to Canada moved on to North America.

Nineteenth Century Emigration

From 1815 onwards, Catholic emigration became more prevalent. In fact, from 1815 until the beginning of the famine in 1846, a staggering number of people left the country. Between 800,000 and one million Irish men and women sailed west, with half settling in North America and the other half going to Canada. South America also attracted a significant number of Irish emigrants during these years.

Such large numbers paint a picture of deprivation in Ireland, even before the devastation of the famine. The potato crop failed fourteen times between 1816 and 1845. British industrialisation also took its toll. For instance, Ireland’s textile industry, a significant source of employment, collapsed because it couldn’t compete with Britain’s new production methods.

To make matters worse, changes in land use at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 saw farm labourers squeezed out. As the English army no longer required large amounts of grain, many Irish landowners switched to rearing cattle. That meant fewer jobs for farm hands.

New Irish Communities

Newfoundland, with its established Irish community, attracted some of these new immigrants but so, too, did other destinations. For example, large numbers of people from counties Clare, Cork and Limerick arrived in Canada between 1823 and 1825, establishing a settlement in Peterborough, Ontario. Each household received a cow, basic implements and three bushels of seed potato – what a start to a new life in a strange land!

As the century wore on, the numbers of arrivals increased. In 1831 alone, 34,000 Irish immigrants arrived in Quebec. By the middle of the nineteenth century, well-established Irish communities lived in Canada’s three largest cities, Montreal, Toronto and Quebec. By the 1870s, Irish immigrants were the largest ethnic group in every town and city in Canada apart from Montreal and Quebec.

These increasing waves of immigration were not without their problems, however. For instance, in 1827 Anglican governors in Ontario complained about the large numbers of Irish Catholics and Scots-Irish Presbyterians settling in the territory. The building of canals and railroads brought many Irish navvies to these parts; placenames like Killaloe, Barry’s Bay, Limerick Lake, Killarney and Massey Town ensure their memory lingers on.

The Crisis of 1847

There were other problems to contend with, like the spread of disease from new arrivals to the general population. So, in 1832, authorities opened a quarantine station at Grosse Île, a deserted island in the Gulf of St Lawrence near Quebec City.

The famine brought a surge in Irish immigrants. In 1846, approximately 33,000 people of all nationalities landed at Grosse Île. The following year 84,500 landed, two-thirds of whom were Irish. These were the survivors of a gruelling six-to-nine-week journey that claimed many lives.

Early in 1847, Grosse Île’s medical superintendent, Dr George Mellis Douglas, warned the governing assembly of the impending crisis. He sought £3,000 in extra funding but received one tenth of that amount, enough to buy fifty new beds. The first ship arrived in March and filled the hospital to capacity – 200 of its 240 passengers had succumbed to typhus.

The hospital at Grosse Île where thousands died in 1847.

The hospital at Grosse Île where thousands died in 1847.Douglas reported an ‘unprecedented state of illness and distress’ on the ships. By May, fifty people were dying daily, and a thousand sick patients inhabited the island. New sheds were built but still there was not enough space. With no other option available, Douglas confined passengers to their ships. By the end of May, forty ships were anchored at Grosse Île in which 12,500 passengers – the healthy, sick, dying and dead – were crammed together.

A Limerick magistrate who travelled on an emigrant ship described “hundreds of poor people… huddled together, without light, without air, wallowing in filth, and breathing a fetid atmosphere, sick in body, dispirited in heart.” Conditions on the island itself were no better. The sick and healthy were not separated and bedding wasn’t disinfected. Many who arrived in a state of health died from typhus contracted on the island.

Infection Spreads

Douglas warned authorities of the potential for disease to spread. In June, he wrote “of the 4,000 or 5,000 emigrants who have left this island since Sunday, at least 2,000 will fall sick somewhere before three weeks are over. They ought to have accommodation for 2,000 sick at least at Montreal and Quebec, as all the Cork and Liverpool passengers are half dead from starvation and want before embarking.”

Sure enough, typhus epidemics broke out in Quebec City and Montreal. An estimated 20,000 people died. Despite the dangers posed by the starving and sick Irish, the Canadian people showed them great generosity. Clergy and lay people alike tended to them in specially constructed fever sheds. Local people adopted orphaned children.

Anger was expressed against the authorities in Britain however, particularly against the landlords, for “shovelling out the helpless”. Canadian emigration officials complained so loudly that the British government agreed to reimburse Canada for some of the costs involved in looking after these poor immigrants.

Douglas erected a monument at Grosse Île in memory of all those who died. It bears this inscription:

In this secluded spot lie the mortal remains of 5,424 persons who fleeing from Pestilence and Famine in Ireland in the year 1847 found in America but a Grave.

Grosse Île operated as a quarantine station until 1932, although with a fraction of the deaths that occurred in 1847. It became a national historic park in 1993; four years later the government erected a memorial commemorating the Irish who died there in 1847.

Image by Sébastien Champoux.

Image by Sébastien Champoux.The Orange and the Green

Religious and ethnic differences were a feature of life in Canada because of its colonisation by both France and Britain. When it came to Irish cultural identities, both orange and green were represented there, with conflict erupting at times.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Orange Order was very active in Canadian government and public office. At times, Catholics complained about miscarriages of justice when magistrates hearing their cases were members of the Orange Order.

Perhaps the Orange Order feared an alignment between Irish Catholics and French Canadians that might threaten their interests. No such alliance materialised, however. Nevertheless, numerous violent incidents between Orangemen and Irish Catholics took place during these years, with the Twelfth of July and St. Patrick’s Day being particular flashpoints.

After the famine, anger against the British government fuelled the establishment of new political organisations. The Irish Republican Brotherhood was founded in Ireland; America saw the birth of the Fenian Brotherhood. In Canada, however, sympathy for the Irish cause was fraught with difficulty because it conflicted with ideas of good citizenship within the British Empire.

In 1866, the Fenians staged an invasion of Canada with the aim of causing tension between the United States and Britain. Canadian and American forces repelled two such incidents. Although they failed in their objective, these raids indirectly contributed to the political unification of Canada because they highlighted the vulnerability of its border in the absence of a single government.

Canada Unites

Since its colonisation, Canada had evolved into independent territories, but the mood was changing. From around 1864, a group of politicians (known as the Fathers of Confederation) began negotiating terms of a political union in Canada. Their work resulted in the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada joining together to form the Dominion of Canada on July 1st, 1867. Other territories followed suit in the coming years.

While Fenian activity had some impact in driving support for this union, there were other Irish influences at play. At least seven of the Fathers of Confederation were either Irish-born or second generation Irish. The most well-known was Thomas D’Arcy McGee. Born in Carlingford in 1825, McGee joined the Young Ireland movement and wrote for its newspaper, The Nation, as a young man.

McGee left Ireland for America after participating in the rebellion of 1848. He moved to Montreal in 1857 and established himself in politics, eventually becoming a minister in the Canadian government. An opponent of the Fenians, he was a voice of reason during a time of political tension and sectarian violence.

After one clash between the Orange Order and Irish Catholics in Toronto on St. Patrick’s Day in 1858, McGee persuaded the city’s Irish Catholics to give up the right to publicly celebrate their national holiday. He took the sting out of this move by simultaneously running a campaign against public recognition of the Orange Order.

In April 1868, a Fenian sympathiser assasinated McGee. He is remembered in Canada as an advocate for minority rights at a time when politics was filled with ethnic and religious tensions. A good-natured and sociable man who was passionate about Canadian interests, he left his mark on the political landscape. Eighty thousand people attended his funeral.

Irish Canadians in the Twentieth Century and Beyond

Irish emigration to Canada continued throughout the twentieth century, although the numbers declined in comparison to the great exodus years of the 1900s. Between 1870 and 1970, around 400,000 Irish immigrants arrived in Canada. That figure contrasts sharply with the million Irish souls who travelled there during and immediately after the famine.

During the twentieth century, Irish-Canadians continued to involve themselves in Canadian public life. Many served in the armed forces during both world wars. Nelly McClung, the daughter of an Irish farmer, was one of the “Famous Five” group of political activists who won a landmark court case in 1928 securing the right for women to enter politics.

Irish-Canadians who have reached high public office in more recent years include Brian Mulroney, a son of Irish immigrants who served as Prime Minister from 1984 to 1993, and Mark Carney, who had three grandparents from Mayo and served as governor of the Bank of Canada until 2013. Carney played a key role in helping the Irish government negotiate a solution to its banking crisis in 2008.

In December 2011, the Irish Canadian Immigration Centre (I/CAN) was set up to help Irish people settle in Canada. Irishman Eamonn O’Loghlin, a leader of the Irish community, was instrumental to the establishment of this non-profit organisation. He led the committee that founded the centre and lobbied the Irish government and Irish organisations across Canada for start-up funding.

Eamonn, who was a tireless advocate for Irish immigrants, died in 2013. In 2009, Toronto’s Irish community honoured him with an ‘Irish Person of the Year’ award. In his acceptance speech he said, “with new immigrants arriving in bigger numbers, we need to lend a helping hand and perhaps remember back to when many of us, as new immigrants, received a helping hand.”

The Irish Influence

The Irish contribution in Canada is far-reaching. So many Irish immigrants worked on large construction projects that it could almost be said the Irish built Canada. Of course, St Patrick’s Day is widely celebrated in Canada, and Montreal proudly lays claim to the oldest parade in North America, held since 1824.

Irish cultural influences, too, are etched into Canada’s social landscape. Canadian folk music, for instance, draws on Irish folk music for its inspiration and style. More than fifty Canadian third-level institutions teach the Irish language. There is even a Gaeltacht region in Ontario which the Irish government recognises.

That other famous Irish institution, the GAA, is also active in Canada. The Canadian Gaelic Athletic Association was founded in 1987. There are now twenty-four GAA clubs across Canada with new clubs under development.

It would be a mistake to think that this social and cultural traffic was all one-way. Money sent home by emigrants lifted many out of poverty in Ireland. Perhaps just as important was the flow of new ideas and expectations back home. While it’s certainly true that Irish immigrants left their mark on Canada, it’s also true that our brave emigrants changed the face of Ireland from their new homes thousands of miles away.

Article first appeared on www.oldmooresalmanac.com