THE 1916 Easter Rising remains one of the most pivotal events in Irish history, despite the fact that the it ultimately ended in failure.

Continuing with our retrospective on the uprising, we come to the day when it all came crashing inwards, when Irish hopes of easing Britain's stranglehold on the country died, along with dozens upon dozens of volunteers fighting for freedom.

Closing in

Following the arrival of thousands of British reinforcements over the previous few days, the rebels found themselves totally surrounded, totally outnumbered, and losing their grip on the centre of the city.

Dublin General Post Office (GPO), which was established as the rebels' headquarters on the first day of the Rising, was in ruin following two days of shelling and a fierce firefight the night before.

British soldiers had mouse-holed their way through the surrounding buildings to all but totally flush out any defence the GPO had.

Much of the centre of Dublin had been destroyed by artillery fire, and the rebels, hunkered in the smoking remains of their headquarters, knew defeat was imminent.

Surrender

Before the building collapsed, the rebels evacuated, and established a makeshift headquarters on Moore St.

From here they planned a breakout, where they'd tunnel through a number of nearby buildings and attempt to escape the city.

But Patrick Pearse, who had been selected as president of the Irish Republic just six days earlier, decided against it.

Due to the shockingly high amount of civilian causalities throughout the last few days (260 were killed and over 2,000 were wounded), Pearse made the decision to surrender, in order to save any further loss of life.

On the 29th of April, Pearse wrote an official statement of unconditional surrender to Brigadier-General Lowe, which read:

"In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government present at headquarters have agreed to an unconditional surrender, and the commandants of the various districts in the City and County will order their commands to lay down arms."

atrick Pearse, accompanied by Elizabeth O'Farrell, surrendered, ending the Easter Rising, “to prevent... further slaughter.”

atrick Pearse, accompanied by Elizabeth O'Farrell, surrendered, ending the Easter Rising, “to prevent... further slaughter.”The surrender order given to nurse Elizabeth O'Farrell. She was handed a Red Cross insignia and a white flag and asked to deliver the surrender to the British military.

She emerged into Moore St. with heavy fire surrounding her, but it eventually stopped when the British noticed her white flag.

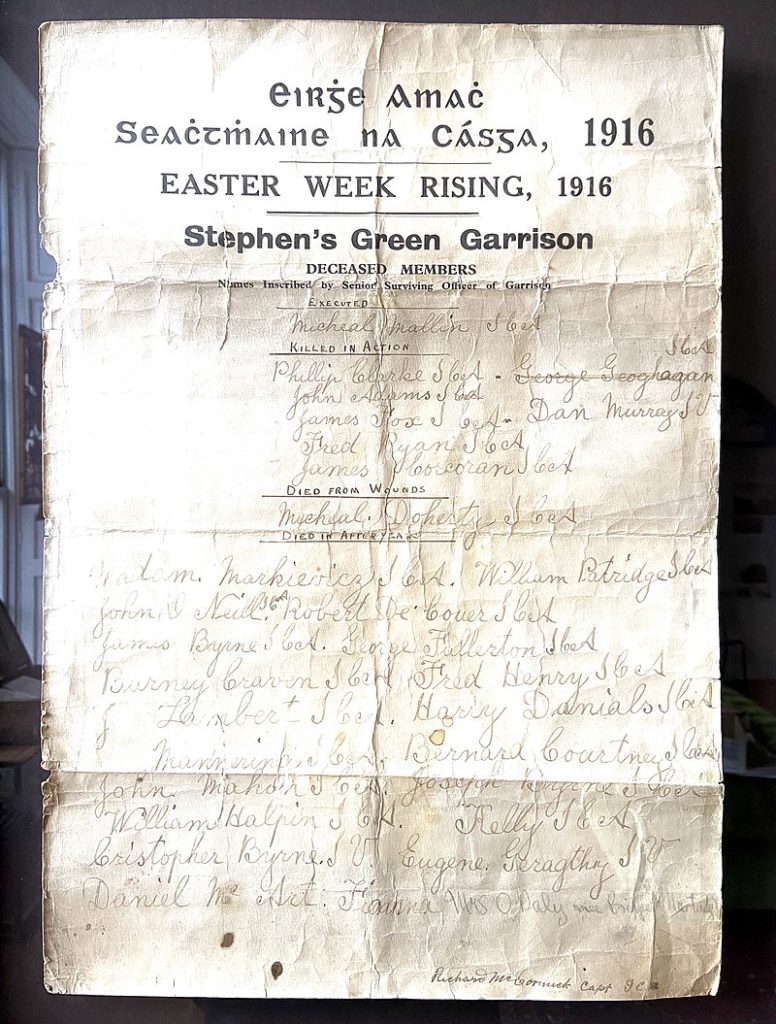

Aftermath, arrests and executions

Surrender, sadly, wasn't the end for the rebels. A price would have to be paid for the insurrection, and it was costly.

British generals ordered that every person responsible for the uprising be rounded up and arrested, and over the next few days, a total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested, including 425 people for looting.

Military courts were quickly set up to try each and every one, and shamefully, these sessions were held in secret and were anything but fair.

90 of those arrested were sentenced to death, despite the fact that the British general in charge had stressed that only the "ringleaders" and those proven to have committed "coldblooded murder" would be executed.

Due to the makeshift nature of the courts, the evidence presented was weak, and so plenty of those executed had very little - if anything at all - to do with the Rising.

The most prominent person to escape execution was Éamon de Valera, who would go on to become President of the Irish Republic, as well as the nation's first Taoiseach.

During the first two weeks of May, many of the key figures of the Easter Rising were killed, including President Pearse and James Connolly, who had led the rebels in battle.

As the executions went on, the Irish public became increasingly hostile towards the British and sympathetic to the rebels, and Irish members of parliament pleaded with the British Prime Minister to stop, arguing that continuing was only hardening the Irish resolve and strengthening their hatred of the British.

"Thousands of people who ten days ago were bitterly opposed to the whole of the Sinn Fein movement and to the rebellion, are now becoming infuriated against the Government on account of these executions," one Irish MP told parliament.

"It is not murderers who are being executed; it is insurgents who have fought a clean fight, a brave fight, however misguided."

He was heckled by his fellow English MPs.

Following Connolly's execution on May 12, the British gave into pressure, and sentenced all those awaiting execution to penal servitude.

The likes of Michael Collins, Éamon de Valera and J. J. O'Connell would survive due to this, and began to plan the coming struggle for independence.