A DONEGAL man hanged in a high-profile murder case in London in 1883 may have been the victim of a miscarriage of justice according to newly discovered evidence from an archive file closed to public scrutiny for over 100 years.

The evidence from a British Home Office file suggests that an Old Bailey judge, Mr Justice Denman, who heard the case against Patrick O’Donnell accused of the murder of the Invincibles leader James Carey, withheld crucial information in court which indicated that the jury believed that the killing was ‘without malice aforethought’.

A killing ‘without malice’ would equate to manslaughter and would have been punishable then by a short prison sentence rather the mandatory sentence of hanging which arose in cases of murder ‘with malice aforethought’.

Mr Denman presided at the trial of Patrick O’Donnell, a 45-year-old labourer with no formal education, charged with the murder of James Carey, who led the Invincibles, the group responsible for the Phoenix Park murders in which two of the most senior political figures in Ireland, Thomas Burke and Lord Cavendish, were viciously stabbed to death in Dublin in May 1882.

In order to avoid conviction Carey turned informer and gave evidence against his colleagues, five of whom were hanged in 1883.

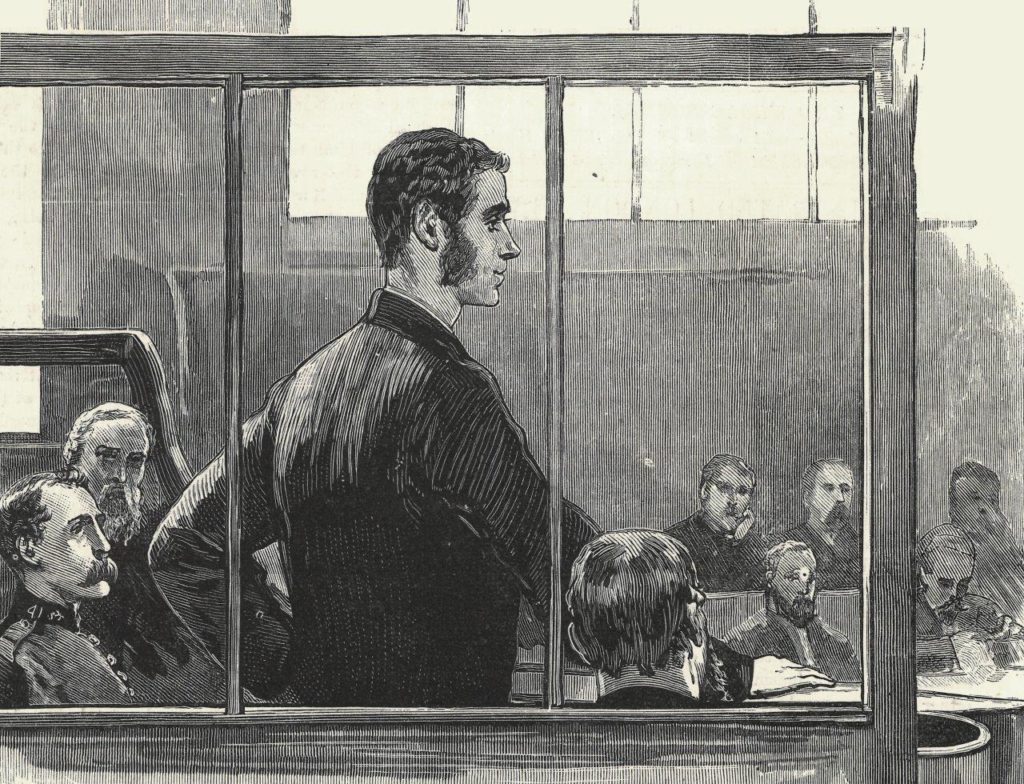

A sketch of Patrick O'Donnell in the dock of the Old Bailey (London Weekly Illustrated, 1883)

A sketch of Patrick O'Donnell in the dock of the Old Bailey (London Weekly Illustrated, 1883)A newly published book ‘The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell’ and a TG4 drama-documentary of the same name, reveals for the first-time evidence found by author Seán Ó Cuirreáin which suggests that Mr Denman misled the court, including the defence and prosecution teams as well as the press, when he amended and misrepresented the wording of a direct question from the jury which showed they were inclined to believe the killing was ‘without malice’.

Mr Denman told the court that the jury, as they concluded their deliberations having heard all the evidence, had submitted a question to him in writing in which they had sought a definition of ‘malice aforethought’.

His reply was widely reported by the media who attended the high-profile case.

However, the actual question posed by the jury which was not read to the court is included in a file on the O’Donnell case in the British National Archive which was ordered to be ‘Closed until 1985’.

The handwritten note of the jury’s question in blue pencil was attached by Mr Justice Denman to 61 pages of meticulous notes made by him during the course of the two-day trial in a document which was subsequently ordered to be closed to public scrutiny until 1985.

A portrait of Mr Justice Denman (National Portrait Gallery)

A portrait of Mr Justice Denman (National Portrait Gallery)The question suggests that the jury had no problem in understanding the concept of ‘malice aforethought’ but rather sought to ascertain if they reached a verdict of ‘murder without malice aforethought’ would the judge accept that verdict.

The text of the question was: “If we find prisoner guilty of murder without malice aforethought can you take that verdict”.

“It is highly significant that the judge misrepresented the jury’s question, withheld it in court and replaced it with an unasked question of his own” says Seán Ó Cuirreáin.

“This was a critical deflection by him which left the defence team in the dark and paved the way to a guilty verdict.

“The suggestion that the jury sought the judge’s approval for a verdict that the killing was without malice and the distortion of their legitimate query was, in fact, a matter of life or death for O’Donnell,” he added.

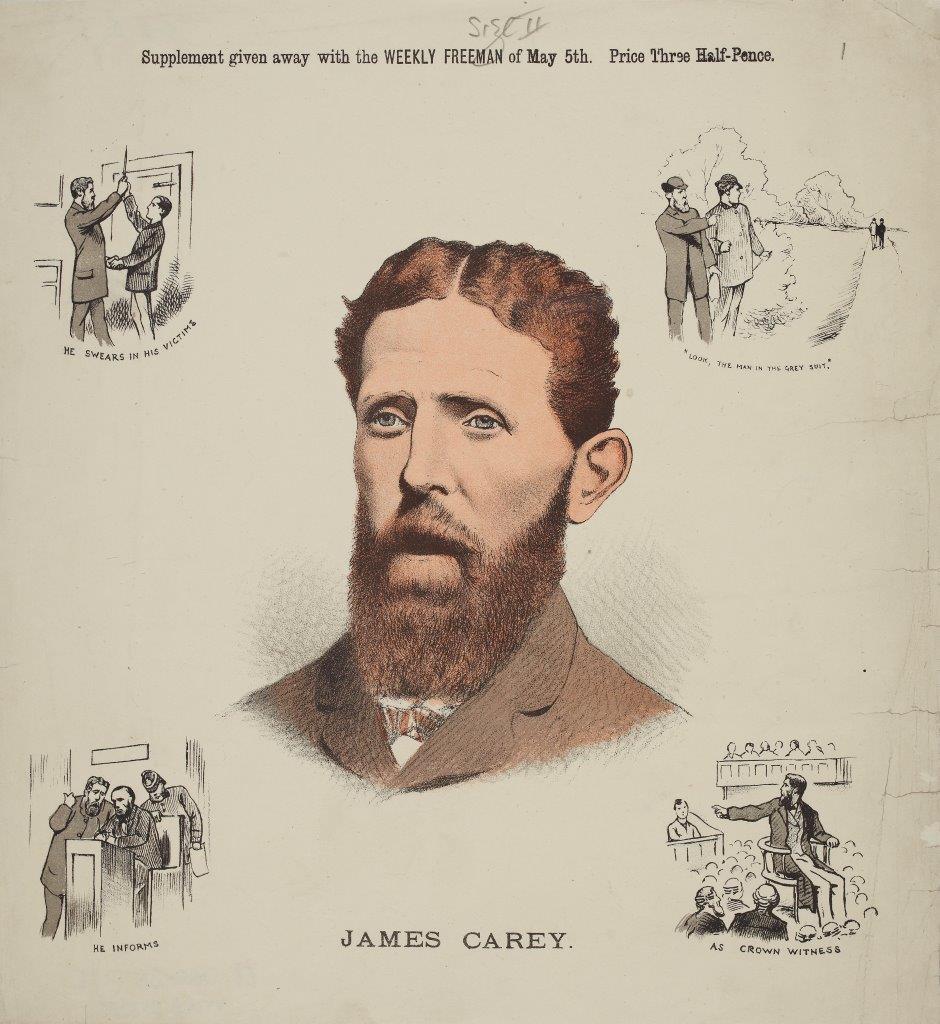

James Carey sketch in The Weekly Supplement (National Library of Ireland)

James Carey sketch in The Weekly Supplement (National Library of Ireland)Ó Cuirreáin noted as ‘significant’ that no reference was made to the jury’s question in the official transcript of the trial. All of the newspaper reports on the trial refer only to the judge’s amended question as reporters were unaware of true nature of the jury’s query.

An earlier question posed by the jury was read in full to the court by Mr Justice Denman and his response to it attracted criticism from the defence team who said it favoured the prosecution case and was biased against Mr O’Donnell. This too was omitted from the official trial transcript.

Patrick O’Donnell, who was born in the Gweedore Gaeltacht but had spent much of his life in America where he had become accustomed to carrying a gun, admitted to shooting Carey in front of witnesses but his defence was that the killing was in self defence.

He had abandoned America and was travelling to South Africa where he hoped to make his fortune in the diamond mines there when he unknowingly befriended Carey during the three-week sea voyage from London to Cape Town as the informer and his family attempted to flee into hiding under an assumed name.

Carey was one of the most reviled and despised figures in Ireland at the time and his evidence against colleagues who were later hanged was seen as treachery.

O’Donnell was lauded as a hero for killing the informer whose death was celebrated throughout Ireland and in the Irish-American communities where he had spent half his life.

The Celtic Cross erected in memory of Patrick O'Donnell at Glasnevin Cemetery

The Celtic Cross erected in memory of Patrick O'Donnell at Glasnevin CemeteryAn ‘O’Donnell Defence Fund’ established in America accumulated $55,000 (c. €1.5 million now) to employ a high-powered legal team to defend him.

Since O’Donnell had been granted American citizenship during his years there, the US President pleaded that the sentence of death be postponed pending efforts to mount an appeal.

The iconic French writer Victor Hugo also took up his case and contacted Queen Victoria directly with an urgent request to spare the Donegal man’s life.

Such appeals were rejected and O’Donnell was hanged at Newgate Prison on December 17, 1883. His death secured his immediate status as a national hero at home and abroad and he was celebrated as an Irishman who had died for Ireland.

Two large Celtic crosses were erected to commemorate him, one in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, the second in his native Gweedore, where a public event in his honour is still celebrated annually.

The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell is published by Four Courts Press, price €17.95 (paperback) and available here or from all good local booksellers.

The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell is also the title of the feature-length drama-documentary commissioned from independent production house ROSG by TG4. It will receive its worldwide premiere at the Galway Film Fleadh this week.