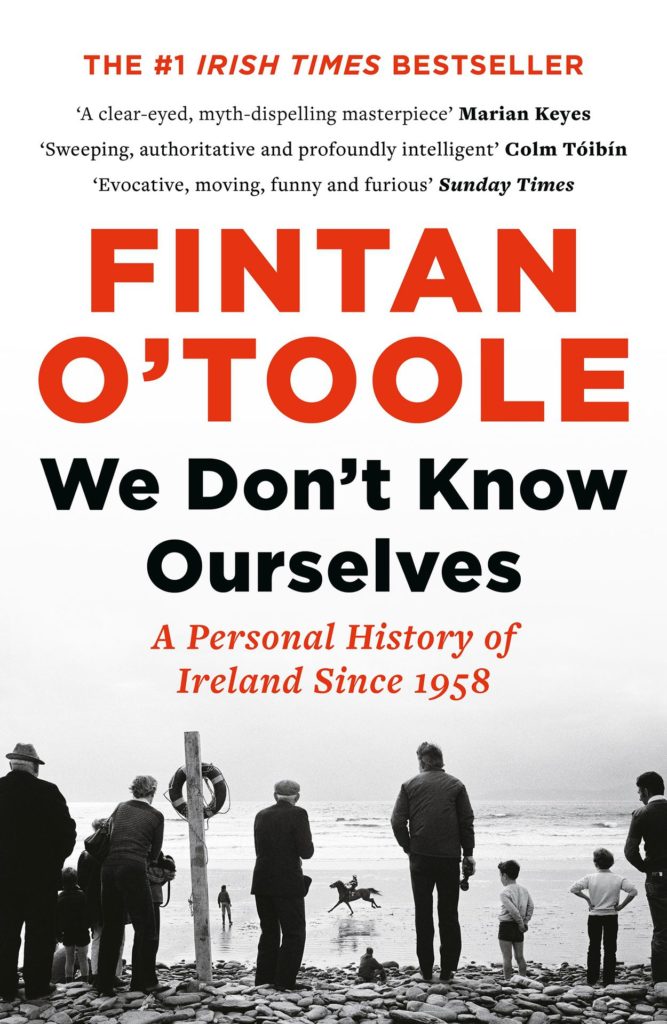

Journalist Fintan O’Toole’s book We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland, just published in paperback, explores the roots of the conflict in Ireland and implications of the peace deal that ended the Troubles in the North. JUSTIN CHAPMAN reports in the wake of President Joe Biden’s visit to Ireland

JOURNALIST Fintan O’Toole points out in We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland that the Good Friday Agreement enshrined national self-determination, largely put an end to the armed conflict in the North, and recognised sovereignty and citizenship as a matter of free choice for those living in Northern Ireland.

In his book, O’Toole weaves his personal story into the fabric of Ireland’s history and culture, from his birth in 1958 to the present day, including mass emigration, nationalism, the Troubles, Brexit and more.

Leading into the Troubles, Ireland experienced decades of mass emigration. O’Toole write that three out of five children growing up in Ireland in the 1950s were destined to leave the island. This reporter’s grandparents, who left Ireland that decade in their 20s and landed in Pasadena, never saw their parents again.

“It really was tragic for a lot of families, that they were broken up by mass emigration,” O’Toole said. “The promise was that if we only had our own state, this mass migration would stop, we would be able to do things for ourselves and make life better. And here people were voting with their feet against the viability of an independent Ireland.”

The government opened the country up to foreign capital, beginning a long economic transformation from an agricultural economy to a globalised one.

Up in Northern Ireland, however, trouble was brewing. The Catholic minority there rebelled against civil rights abuses by the UK and Protestant majority, resulting in civil unrest and the armed campaign of the IRA.

O’Toole writes that the eruption of violence in Northern Ireland was “both sudden and slow. On the one hand, very few people expected it. On the other hand, there was the slow burn of “50 years of neglect, apathy and misunderstanding. Nobody thought in 1968 that this was going to go on for 30 years. But it also felt like it could’ve gone on for another 30. It was self-generating.”

The seed that led to the Troubles was the partition of the six counties in Northern Ireland from the rest of Ireland dating back to the 1920s.

Partition “made it possible for [Ireland] to be an ethnic and religious monolith” and lack “the pluralism you need to have a modern democracy,” O’Toole said. “What was left was just an overwhelmingly and, frankly, stultifyingly Catholic country. How do you preserve this idea of being the most Catholic country in the world? By punishing women, in particular. So you had a sexual puritanism, which even by the standards of the time was extreme.”

O’Toole pointed out in his book that Irish people considered the Republic free and the North unfree, but for women who couldn’t buy contraceptives or get abortions in the Republic, the UK was freer.

Today, O’Toole said, the Catholic Church in Ireland is “a hugely diminished institution. The real damage it did was entirely self-inflicted through that appalling handling of all these child abuse scandals. Institutionally, it became rotten.”

Ireland has gone through a transformation socially, politically and economically in a relatively short period of time. Divorce was legalised in 1995, same-sex marriage in 2015 and abortion in 2018, which is quite remarkable when you consider the stranglehold the Catholic Church had on Irish politics and culture not too long ago. “These were markers of a profoundly changed society,” O’Toole believes..

Leaning into its diaspora in the United States and elsewhere, Ireland has developed its Global Ireland brand.

O’Toole, also a professor at Princeton University, said it’s moving to see how many people in the United States claim and are proud of their Irish heritage. “It’s important to them, it’s part of their own identity and it doesn’t make them not American,” he said.

O’Toole, 65, said that while he never thought he’d see Irish reunification in his lifetime, his thinking has shifted in recent years.

“I’m not so sure about that anymore,” he said. “I think there will be a referendum on Irish unity in Northern Ireland within the next 10 years. My worry is that we’re not ready for it yet. We still have quite a lot of work to do. I would much rather we have reconciliation before unity, rather than unifying with a still very divided population.”

He explained that Brexit has made Irish unity more likely, because being in the EU kept Catholics in Northern Ireland reasonably satisfied. A majority of Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU, so Brexit has alienated the Catholic population again.

“The irony is this was a situation brought about by people who are unionists, not by Irish nationalists,” he said. “This misconceived unionist project actually did more harm to the UK and Northern Ireland’s place within it than the IRA managed to do through 30 years of violence.”

Justin Chapman is an award-winning journalist, author, actor, and politician. He writes for Alta Journal, Huffington Post, LA Weekly, and many other publications