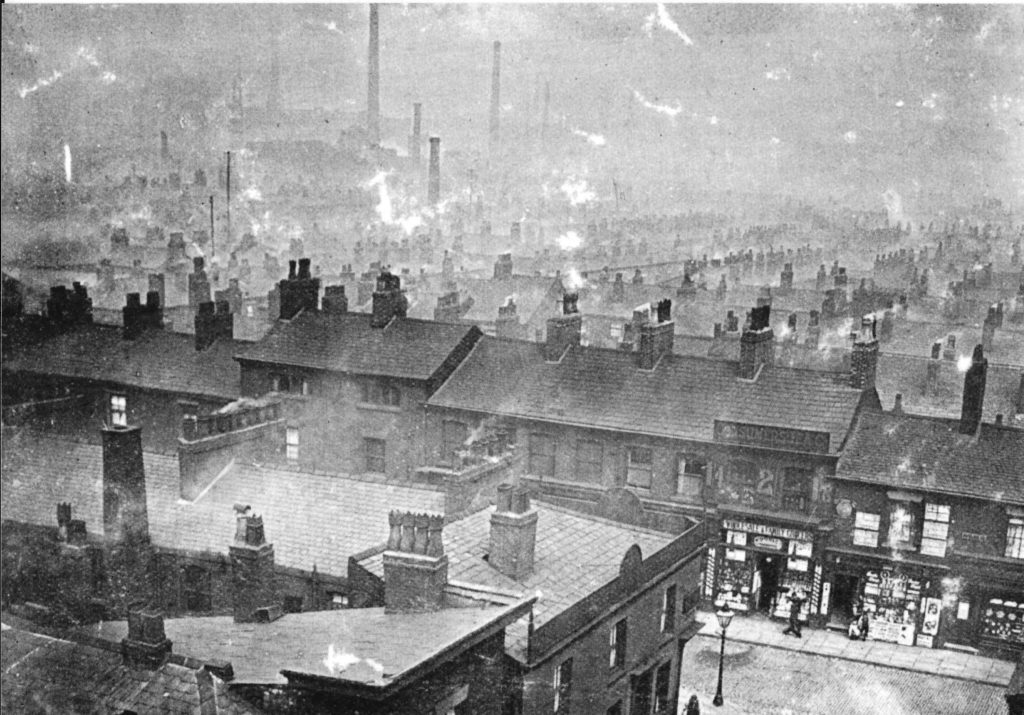

MANCHESTER in April 1921, 100 years ago, was a very different place than it is now, especially for the large Irish immigrant community that lived there.

From the days of the Famine onwards droves of impoverished people had come over from the villages of rural Ireland to seek work in Manchester, the heart of England’s northern powerhouse, which was then the most heavily industrialised city in the world.

Around that time about 15 per cent of the population of the city were Irish and invariably they settled in the inner-city districts like Ancoats or Angel Meadow to live in crowded, often slum-like, conditions close to the huge mills and smoky factories that needed their labour.

It is estimated that 35 per cent of the population in Manchester today are of Irish origin, including second and third generations born there.

While in 1921 they lived mainly in the inner-city areas, now, 100 years later, those families and their descendants, as they prospered, have dispersed.

Many are to be found in the leafy suburbs of Cheshire and the outskirts of Greater Manchester and, thankfully, the terrible back-to-back slums that the German philosopher Friedrich Engels once described as ‘hell upon Earth’ - a comment made when he was visiting Angel Meadow - have now been demolished.

Most of the giant mills have gone too, whilst the remainder have been gutted and transformed into luxury apartments and these areas have been redeveloped and given new names, such as New Islington or the Northern Quarter.

Manchester today is unrecognisable from the town I once knew, let alone what it was like when both my parents lived and went to school in Ancoats in the 1900s.

Ancoats in Manchester in the early 1900s had a large Irish community

Ancoats in Manchester in the early 1900s had a large Irish communityTo complicate things for member of the Irish community in the city in 1921, the political situation back then was tense.

Just five years after the Easter Rising and three years after the First World War ended, the War of Independence had been raging for some time.

Tensions were running high in those months before Michael Collins and his colleagues came over to England to negotiate the Treaty that would end the bloody war.

Saturday, April 2, 1921 was particularly tense.

Earlier that day the IRA had brought the ongoing conflict to the English mainland.

They had set fire to a number of farms in the countryside surrounding Manchester and put incendiary bombs in some city centre buildings.

Earlier that day Manchester’s police force, under increasing pressure, made a number of dawn raids on places frequented by the city’s large Irish diaspora.

That action ended that evening with a surprise raid on the Irish Club located at 58 Erskine Street.

The police suspected it was being used as the clandestine headquarters of the Republican activists - it was in fact the headquarters of Manchester’s No. 2 IRA company.

As a team of armed police rushed up the stairs of the Irish Club in Hulme an innocent Whist drive was in progress and the place was full of families enjoying the social atmosphere of the club on a Saturday night as the card game was played across a number of tables.

Tragically, during the raid, which was led by a Detective Inspector Crowther, 21-year-old Sean Morgan, who was minding the door and selling tickets, was killed.

Sean Wickham, who the police were actually looking for, was shot in the neck and injured.

Various Irish people were arrested at the club that night and brought to trial, with those convicted handed down sentences ranging from five years to life imprisonment.

The Irish Club in Erskine Street, Hulme

The Irish Club in Erskine Street, HulmeIn those febrile times it is hardly surprising that the tone of the press was distinctly anti-Irish, making life difficult for those immigrants who were trying to live peacefully with their neighbours while creating a new life over here for their families.

In the press coverage of the Erskine Street raid, and in the subsequent trial, the overwhelming narrative that prevailed was the police version of the incident.

Indeed, Inspector Crowther was later decorated with an award for his bravery rather than reprimanded for being responsible for the shooting of what many believe was an unarmed man.

At the time he was quoted as saying the following:

“We marched across the road and the five of us passed through the door simultaneously. Two armed guards were too surprised to offer any resistance. In half a minute we stood in a brightly lighted room with our revolvers drawn facing the censorious stare of nearly 30 men and women. Not a word was spoken. For 60 seconds we stood there, and during that time my eyes were searching for and found the two men I hoped to see. This was indeed luck. The crowd was ugly and I anticipated trouble. It came. The officers had got their men as far as the door when a shot rang out. Several others immediately followed it. I saw a man fall dead in the passage. Simultaneously someone tried to shoot me, but more by good luck than good management, I shot him first. My bullet sheered away the fingers of his right hand. Perhaps for five seconds hell was let loose. At the end of it I found myself with my back against the door bellowing orders to the crowd remaining in the room to keep their hands up.”

Another Detective named Bolas gave his version by saying that as they entered the building Sean Morgan confronted them with a revolver in each hand, so he shot him dead and he also shot Wickham.

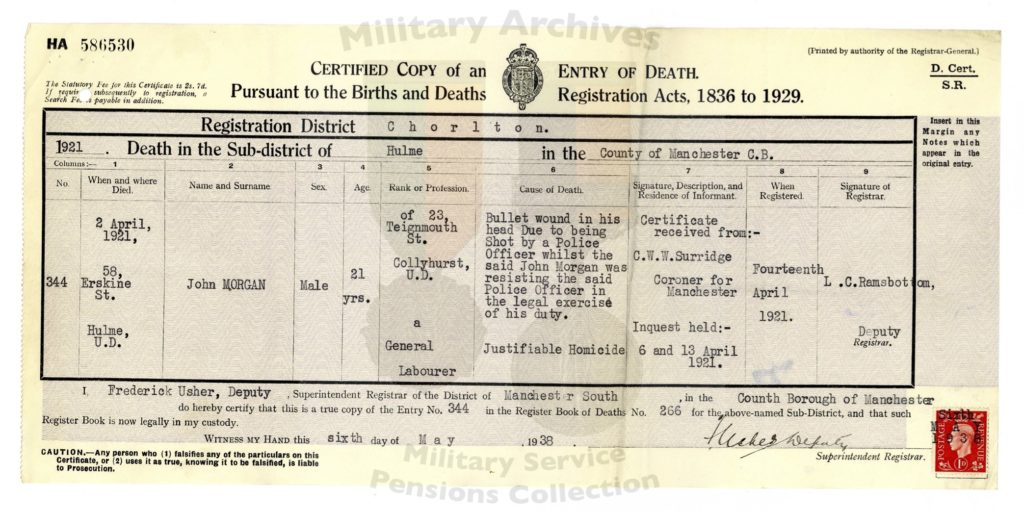

Yet, despite this being at variance with the evidence of his boss, the judge at the trial picked up no discrepancy and the inquest recorded the cause of death as: “Bullet wound to the head. Due to being shot by a police officer whilst the said John Morgan was resisting the said police officer in the legal exercise of his duty. Justifiable homicide.”

John (Sean) Morgan's death certificate (PIC: Military Service Pensions Collection)

John (Sean) Morgan's death certificate (PIC: Military Service Pensions Collection)All this was taken as the truth and there are some other accounts in the archive of the Bureau of Military History that suggest Morgan was indeed armed.

At the trial the 16 arrested on the night, or over the following days, were sentenced to a combined total of 121 years.

That would have been it for posterity had not a vivid eyewitness account emerged years later.

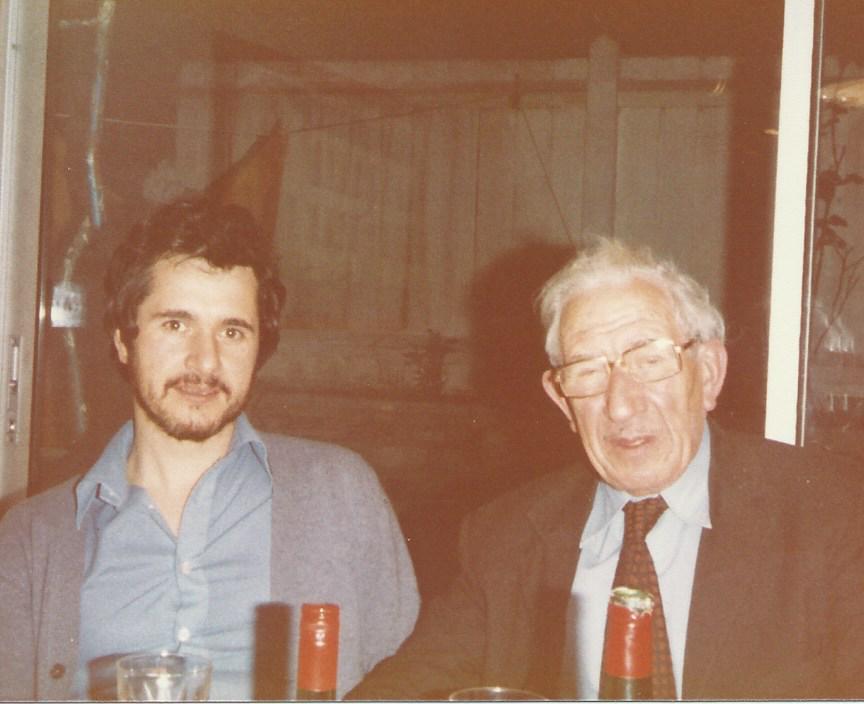

In about 1975 some 54 years after the dramatic events, my father Alex McDonagh was visiting our home in London and over dinner with my mum and my wife and a little lubricated by the wine and a glass of Powers Gold Label, my dad started to relate stories of his childhood and his life in Manchester.

I realised I would never retain all the detail, so I surreptitiously grabbed my work d

Dictaphone from my shoulder bag and switched on to record him.

Dad had an incredibly accurate memory and an eye for detail and apart from being just a year or two out in the length of some of the sentences of those convicted, when checked all the details of his other stories proved accurate.

This now historic tape languished in a drawer unheard until a few years ago when I got my son to digitise the old tape format so I could listen to it.

I was fascinated and astonished as I transcribed my late father’s voice and heard this remarkable account from a 14-year-old schoolboy caught up and observing that unforgettable night.

Now 100 years later you can read here the version of an eye-witness man on the spot, my dad.

Michael J McDonagh with his dad Alex McDonagh, who was at the Irish Club on the night of the raid

Michael J McDonagh with his dad Alex McDonagh, who was at the Irish Club on the night of the raidThe events of April 2, 1921, at the Irish Club, Erskine Street, Hulme, according to Alex McDonagh (1906-1986)…

The victims

“It was Sean Wickham that I saw get shot in a club in Erskine St in Hulme. A fellow called Morgan was killed. He is buried in Moston Cemetery. I was 14 in 1921, I saw him get shot. Sean Wickham, a university man, was the son of the Wickham’s Brewery family. He got 14 years. Sean Barratt was an idealist who wrote books, he got 15 years. A boy nearer in age to me, Danny McNichol, a painter, he got five years. I was once with Danny McNichol and we went and got some bullets and put them on a tramline to get them flattened (he laughs.). Agnes (my father’s sister) said to me I’ve got a cutting of the police proceedings, but she never gave it to me. It was a dreadful tragic affair."

Surprise raid

"It was a Whist drive, a normal Whist drive for charity. Peg (another sister) was there and a girl called Annie Higgins they had a shop there in Hulme and left after to open a shop in Dublin. I remember it very well. I was probably the youngest person in the place. It was a warehouse building and it was empty, the club for the Whist drive was on the top floor. They had probably rented some empty rooms there. You went up a staircase and in the room there was a stage, a mock stage with green curtains and in the room were tables laid out for the cards and at the interval there were refreshments, tea and cake. I remember this very well. As usual with these incidents, there was an informer and I could recognise him to this day. And could describe him, well there were actually two of them, Gillmartin and Foy. I had been playing Whist and was doing well and was in the running for a prize but it was the interval and the man who was on the door wanted to go for a drink, as they do, so there was a boy Morgan who had only come in to see somebody but the doorman asked him to look after the door whilst he went for his drink. The boy was reluctant, and he said don’t be long as he was going to meet his girlfriend saying, “I can’t stay my girl is waiting for me”. As the doorman went off somebody said to me do you want to have this cake, as they could not eat it, so as I was eating it when there was a bit of a commotion at the door with the boy and some men rushed in. There was a commotion and panic. Detectives came in, about eight of them, in raincoats and it all went quiet as they were looking for someone specific, so they went up to people and turned them around and after about the fourth it all went very quiet as more police came in. I saw the two informers, who I had just been thinking were better dressed, than the rest of us, with a nice blue shirt and suit on. Both suddenly took a dive under the curtain on to the floor and were never seen again. The police picked out two people but the two informants had now gone. When I hear the expression ‘climbing up the wall’ it makes me cringe because I saw people actually climbing up the wall…I saw girls climbing up the wall, the Walsh sisters. Demented, frightened to death...and there was Sean Wickham and a fellow called Harding came and pulled a gun out. Later on it was in the papers as a Detective got decorated for this and I felt like contradicting it."

Shots fired

"The police pulled the gun first. Sean Wickham tried to push Sean Morgan out of the way, but he got shot and was killed and the next bullet went into Sean Wickham’s neck. I can see it now just under his collar. He was very brave about it. Then they cleared everybody out. Morgan died but Wickham didn’t. He was a university student and real patriot and he had been paying out of his own pocket to help people who were coming over here to get a start and I thought the world of Sean Wickham. He was a real intellectual."

Having read this account from my father recalling his memories as a 14-year-old schoolboy you can draw your own conclusions, but I know who I believe, even as I now reflect how positively things have changed here in England for the Irish community.

Paddy O’Donoghue, who was head of the IRA Unit in Manchester, was later arrested and it was he who had made the first wax impressions to make the key used by Michael Collins to free De Valera from Lincoln Jail in 1919.

During the Erskine Street trial in July 1921, a truce was agreed in the War of Independence.

When the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed by Michael Collins in December 1921 it was agreed that the prisoners relating to the incident in Manchester, including Sean Wickham and O’Donoghue, were to be released in February 2022.

Thankfully now 100 years later all that conflict and bloodshed is behind us and the large Irish Manchester community have long since lived in harmony with their neighbours.