MAL ROGERS journeys to southeast Ireland to cast his eye over an incident that embraces Ireland, Britain, France, Germany — and a tin box.

I STUMBLED across Glencree German War Cemetery in Co. Wicklow some years ago. I’d been walking in the Wicklow Hills with a friend — coincidentally a German — and we’d enjoyed a meal at Johnnie Fox’s pub. Later, with the light fading, we drove towards Enniskerry. Rounding a corner we spotted signs for this odd cemetery in the middle of the Irish countryside.

The image stuck in my mind, partly because of the poignancy of these young men — mostly in their twenties — taking their eternal rest in Irish soil.

At the time, as I wandered through the little crosses, I didn’t realise that one of the 130 or so graves there was almost certainly connected to a mystery that may never be solved.

My second visit, more recently, was focused on that mystery, and the various details that I’d built up in the intervening years.

It was early morning when I arrived in Glencree; a tarpaulin of drizzle shrouded the graveyard. The cemetery is surrounded by mature conifers, soughing in the breeze. The trees condemn the tight little parcel of land to permanent gloom.

Pillars of mist floated through the graveyard as I stared at the small stone crosses, each no more than a foot high, standing in silhouetted rows.

Facing down the valley is a memorial stone, bedecked with wreaths, and personal messages in German, some flowers, a few cards, ribbons.

The substantial monument of black granite carries an inscription in English as well as Irish and German. It reads:

"It was for me to die

Under an Irish sky

There finding berth in good Irish earth.

What I dreamed and planned

Bound me to my Fatherland.

But war sent me

To sleep in Glencree.

Passion and pain

Were my loss — my gain

Pray as you pass

To make good my loss."

I was looking for the graves of Corporal Alois Mittermeyer, Flight Sergeant Hubert Mderzewski, Leading Aircraftman Josef Niebaur, Herr Herbert Rumf and Herr Rudolph Peschmann. They weren't buried together, but scattered among some 130 other headstones. I located them all; none had been tended in a long time. I cleared grass and weeds from each one; not muc else I could do.

The five men were the crew members of a Heinkel bomber which had crashed in a field that bordered the beach at Carnsore Point, in Co. Wexford.

From Wicklow to Wexford

Standing at the southerly end of the beach at Carnsore Point, your feet sink into the sand where it turns very shingly. The tides have moulded the beach into deep furrows, and the winds that batter the coast have swept a lot of loose shingle onto to the tough, wiry marram grass. From this vantage point you can look towards the Leaning Tower of Tagoat. Not quite as famous as the one in Pisa, but impressive in its own way. The tower in question is part of the remains of a Norman castle on Lady's Island.

Just to one side lies Nethertown, and what is known as Aeroplane Field.

The conundrum that I was focused on has its roots in the crash that happened here just 80 years ago.

On June 10,1941 a Heinkel III bomber crashed into that field, killing all five crew members. They were subsequently buried with full Nazi military honours at Crosstown Cemetery in Co. Wexford.

Although news reports were muted at the time, images captured by a local photographer show that Irish soldiers along with Nazi troops in strident black and gold uniforms, and holding swastika-bedecked flags, formed a guard of honour for the five crewmen.

It later transpired that although the Heinkel III was a bomber, it was not carrying a full payload of ordnance. Based at Buc near Versailles, it belonged to a branch of the Luftwaffe collecting meteorological data for weather forecasting.

The plane had taken off from Buc early that morning and had made its way across the southerly part of the Irish Sea. It had been spotted by pilots from the RAF 32nd Squadron operating from Pembrokeshire.

The klaxon began to croak, and two Hurricanes, piloted by Czechoslovak-born Sgt. Frantisek Bernard and French-born Flight Officer Maurice Remy scrambled.

They engaged the Heinkel and strafed it with bullets, damaging it irretrievably. The Luftwaffe aircraft heeled towards the Irish coast, and with smoke pouring from its port engine, and losing height, it limped toward the coast of Co. Wexford. It eventually crashed approximately 100 yards inland about half a mile north of Carnsore. Point. It exploded and disintegrated. None of the crew survived,

and were removed by ambulance to Wexford Military Barracks.

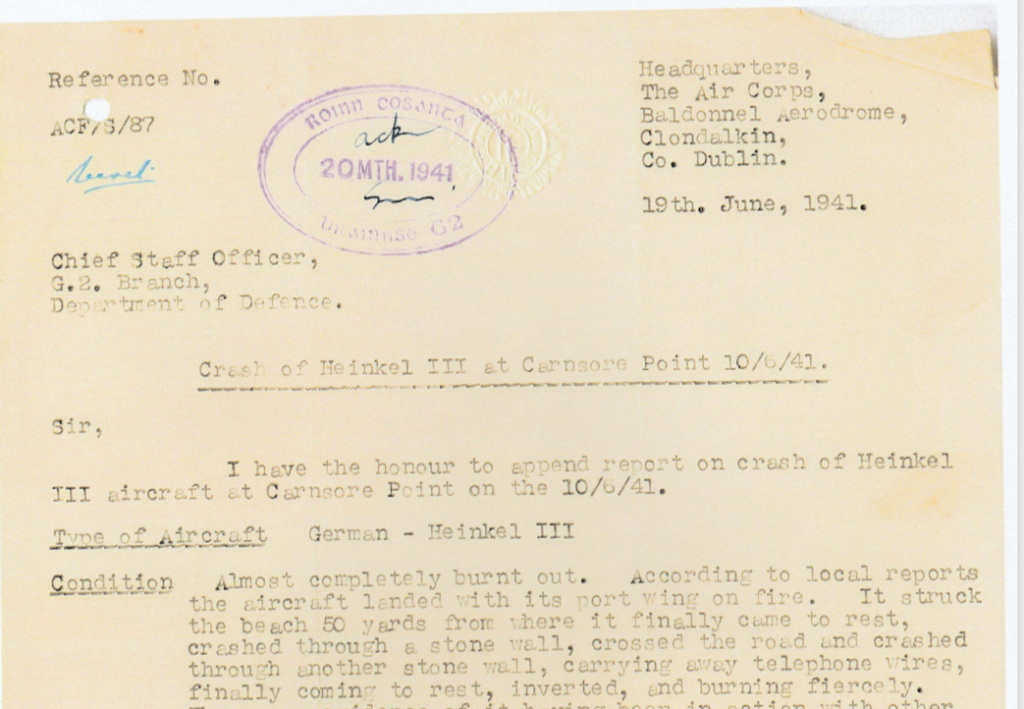

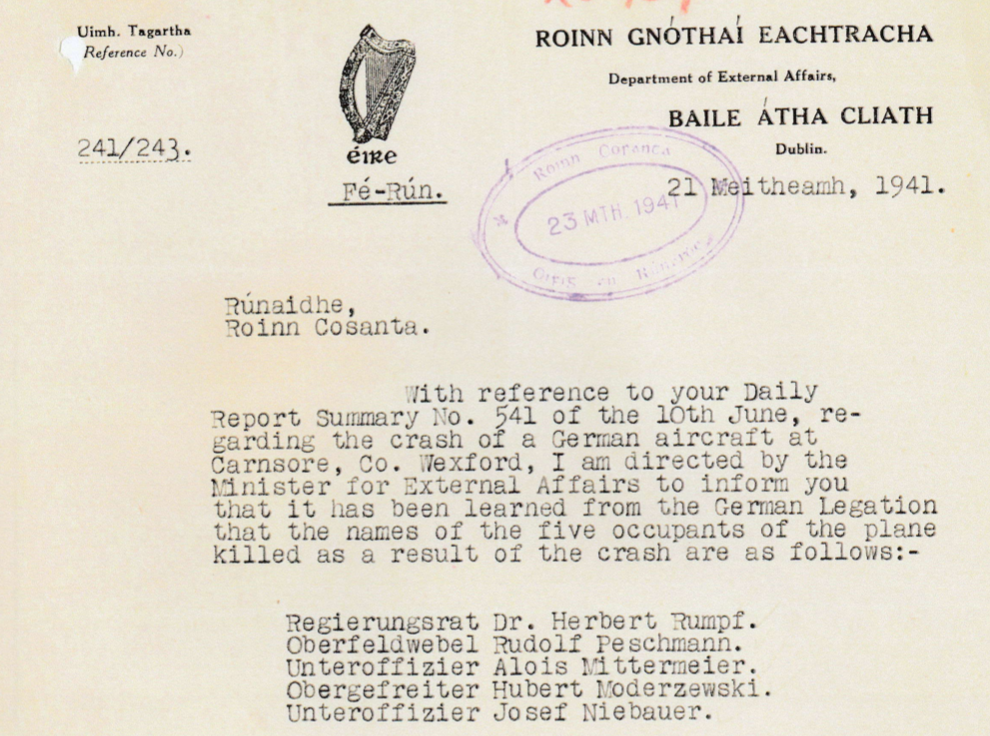

Communication on the report detailing the crashed aircraft.

Communication on the report detailing the crashed aircraft.

The message from Deuteronomy

In September l94l, three months after the plane crash, gardaí in Rosslare Harbour received, from a member of the public, a piece of tin tubing with a tiny scroll of paper inside. It had been found at the crash site by a young local lad.

A Mrs Helena Dunne had passed this on to the local garda sergeant. The youth who found the tin had assumed the writing was in German so had taken it to Mrs Dunne, a German national married to a local man.

But it wasn’t in German. Mrs Dunne confirmed that to the guards.

This tin, along with accident reports, documentation and inquest reports, was eventually sent to the Irish Military Archives at Cathal Brugha Barracks, Dublin. There it remained undisturbed for several decades.

The file then came to light fifty years later in the 1990s and the piece of script was identified as being in Hebrew. It was in fact the Shema, with words from Deuteronomy: “We were Pharaoh's bondsmen in Egypt, and the Lord brought us out with a mighty hand.”

These words were traditionally inscribed on parchment and enclosed in a box called a mezua (or mezuzah).

The conclusion, by Professor Ronan Fanning of UCD, was that in all likelihood one of the aircrew of the Heinkel plane was of the Jewish faith.

The words had been written in ink and remained quite legible - ruling out any chance that the box had been washed up on the shore, becoming coincidentally mixed up in the wreckage.

Further research established it was a mezuzah of a type that would have been use during wartime years.

Mezuzas were, and still are, routinely affixed to the door frames of orthodox Jewish houses.

The headstones image on WIkimedia Commons

The headstones image on WIkimedia Commons

It would appear that, in a cruel act of fate, the owner of this mezuza had escaped the Nazi pogroms, only to perish in a country nominally not involved in the war. It seemed likely to Professor Fanning — now deceased — that one of the airmen, in the final moments of his life, had grasped the mezuza with its prayer as some sort of talisman, in the way a Catholic might reach for rosary beads. This final act of one of these airmen, according to Professor Fanning, is why the box was thrown clear of the aircraft and was not melted in the conflagration.

Over the years much speculation has built up about the mezuza. Investigations have tried to establish whether the identities of the five crew men could be traced back to their home towns and whether any evidence of their Jewish lineage existed. But of course such a strategy — and it has been attempted — is fraught with difficulties at such a remove of 80 years Even if all the identities checked out and the air crew appeared to be 100 percent Aryan German according to their papers, it has been speculated that a resourceful young man could easily have managed to pull off an early case of identity theft.

Today the graves of the five airmen in Co. Wicklow are tended by employees of the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge — the German War Graves Commission.

The cemetery holds 134 graves, mostly Luftwaffe or Kriegsmarine (navy) personnel. Fifty three are definitively identified, 28 are unknown, the remainder being of uncertain identity.

It is estimated that as many as 50,000 Jews may have survived the Holocaust by being part of the Nazi armed forces or German civil administration. They managed to survive the war by keeping their identities totally secret. One mistake would have meant the death camps.

A guard of honour at the burial of the five Luftwaffe crewmen (image in pubic domain)

A guard of honour at the burial of the five Luftwaffe crewmen (image in pubic domain)

There are no exact figures available of how many Jews successfully evaded capture through melting into the background through other means.

As I stood at the entrance of Glencree I stared at the little crosses and wondered which one of those graves held a secret of the most poignant kind. Despite many scenarios put forward to explain the presence of this little tin box on a lonely beach in Wexford, it is a mystery that seems likely to remain unsolved.

Thanks to local Wexford historian Kevin Sills for his local knowledge and the endless trouble he took in sourcing documents and photographs.