THE IRISH diaspora, a diverse community with a common heritage, inhabits every corner of the globe. The story of one far-flung community in South America, which grew to become the fifth largest Irish diaspora population in the world, is very interesting indeed.

It’s thought there are 70 million people of Irish descent scattered around the world. That’s pretty amazing when you stop to think about it: tens of millions of people who can trace their ancestry back to a tiny North Atlantic island with less than five million inhabitants!

The link between Ireland and its diaspora is deep and enduring. Generations of Irish emigrants travelled thousands of miles from home, but they didn’t forget the land of their birth. Instead they passed their heritage onto their children and grandchildren so that today, millions of people worldwide have some kind of Irish identity. In the USA alone, thirty-five million people identify themselves as Irish.

The connection between Ireland and its diaspora isn’t all one way. Ireland’s relationship with its international community is so important we enshrined it in Article 2 of our Constitution: “the Irish nation cherishes its special affinity with people of Irish ancestry living abroad who share its cultural identity and heritage.” And in 2014 the government created a new Ministry for Diaspora Affairs.

The largest diaspora population lives in the US. It’s so big it makes up ten percent of the total America population. Canada, the UK and Australia are also home to large communities of Irish emigrants and their descendants. For reasons of language, proximity, or the prior existence of established communities, these were the countries Irish people travelled to. They were the obvious destinations.

The South-American Connection

But would you expect to find a large Irish diaspora living in South America? There are an estimated three quarters of a million people of Irish descent there. Half a million live in Argentina, with most of the rest living in Uruguay, Chile and Brazil. So, how exactly did such large numbers of Irish migrants end up in Argentina?

It’s a fascinating story. Many Irish-Argentinians can trace their ancestry back to Irish settlers who travelled there in the nineteenth century to escape the poverty of home. But even before that, during the Age of Exploration (from the 16th to the 18th centuries) when European imperial powers were colonising South America, Irish people were establishing themselves there.

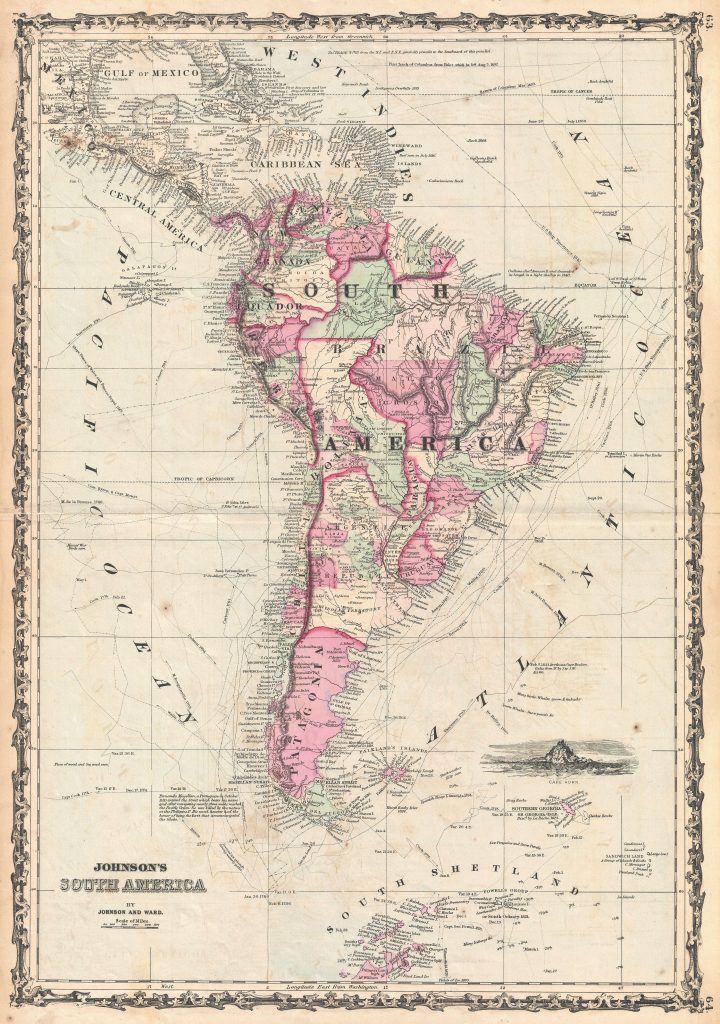

A beautifully detailed map of South America by Alvin Jewett Johnson (1862)

A beautifully detailed map of South America by Alvin Jewett Johnson (1862)

Early Irish Presence in South America

The earliest recorded Irish names in South America are directly linked with Spanish colonisation. Two brothers, Juan and Tomás Farrel were part of an expedition led by Spanish soldier and explorer Pedro de Mendoza. Thirteen ships carrying two thousand people arrived at the Rio de Plata (River Plate) and founded Buenos Aires in 1536.

The first Irish people of note in South America were religious missionaries. Thomas Field (1547-1626) was a Jesuit priest from Limerick who arrived in Brazil in 1577. He established several missions over the following ten years. Spanish and Portuguese priests of Irish descent were sent to the colonies in the late sixteenth century because they spoke English.

Merchants were also attracted to South America. There was money to be made from trading in tobacco, dyes and hardwoods. In 1612 two Irish brothers established a colony at the mouth of the Amazon river, close to English, Dutch and French settlements. In 1620 another Irishman, Bernardo O’Brien from Co Clare, arrived. He and his followers made their living navigating and trading on the waters of the Amazon.

Irish-Spanish Relations

These accounts of an early Irish presence in South America reflected strong links between Ireland and Spain which had endured for centuries. The Milesians, a race of people who arrived in Ireland in ancient times, are thought to have come from Spain. During the middle ages there were solid trade and fishing connections between Ireland and Spain.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an Irish community flourished in Spain. This was thanks largely to the effects of the Protestant Reformation in Ireland. In 1560, Queen Elizabeth I made it compulsory to worship at Church of Ireland churches, with threats of fines and punishments for those who refused. Persecution of Catholics carried on well into the next century, with Cromwell waging war in Ireland from 1649 to 1653, implementing penal laws and confiscating Catholic lands.

King Philip II ruled Spain from 1556 to 1598 during the Spanish Golden Age. Painting by Titian (circa 1550)

King Philip II ruled Spain from 1556 to 1598 during the Spanish Golden Age. Painting by Titian (circa 1550)

As a result, many wealthy Irish Catholic families sent their sons to Catholic universities in Europe instead of England. King Philip II of Spain was a leading figure in the European Counter-Reformation and ties were forged between the Spanish Court and the wealthy families of Ireland.

Wild Geese

While the well-off Irish were sending their sons to European universities and currying favour with the Spanish king, plenty of poor Irish migrants were serving as foot-soldiers in the Spanish army. Many ended up destitute, as evidenced by the large numbers who made their last will at paupers’ hospitals in Madrid.

From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, Irish soldiers served in armies all over Europe. Referred to by historians as the Wild Geese, they were recruited by European powers for their tough reputation. During this time, Irish Catholics weren’t allowed to join the British army, and it wasn’t until the late 1700s that this situation changed. In the meantime European armies were happy to enlist Irish recruits.

The result of all this activity was that by the eighteenth century, there were well-established Irish communities on the Iberian Peninsula, and high-ranking diplomats, military men and politicians of Irish origin in both Spain and Portugal. Even Irish merchants benefited – they enjoyed the full rights of Spanish citizenship.

Military Action in South America

So, it made sense that Irish people and their descendants would travel from Spain to South America during these years. But while early exploration, religion and trade had attracted small numbers of Irish to South America, it was the military action from the end of the eighteenth century that firmly established Irish roots on that continent. By that time there were many Irish soldiers serving in the British, Spanish, Portuguese and South American armies.

Around the turn of the nineteenth century the British army made several attempts to oust Spain as the dominant power at the Rio de Plata. Some of the Irish soldiers involved in these campaigns stayed in Argentina and settled there. Of these, some went on to enlist in the Argentinian army during the Argentinian War of Independence. Others helped to organise emigration from Ireland to Buenos Aires after the 1820s.

Indeed, it was after the 1820s that the bulk of Irish emigration to South America occurred. The largest wave of emigrants travelled there between 1850 and 1870. Many of these people were escaping a famine-stricken land. But even before the famine, there were economic migrants leaving Ireland for South America.

Engraving of emigrants leaving Ireland by Henry Francis Doyle

Engraving of emigrants leaving Ireland by Henry Francis Doyle

From 1803 until 1815, while England was at war with Napoleon, Irish farm labourers supplied grain to feed English soldiers. When this war ended demand for grain fell, prompting many landowners to switch to cattle. Rearing cattle was not as labour intensive as wheat farming, so there were less jobs for Irish farm workers. Emigration increased as a result.

Recruitment of Irish Labourers

The timing was perfect as far as Argentina was concerned. Right from its declaration of independence in 1816, the country was experiencing a labour shortage. The Irish were known to be hard workers and good farmers. By this time there were Irish-born men and their descendants, who had made good in Argentina during Spanish rule, occupying senior positions in the new Argentine army and government. There were also established merchants of Irish descent who had forged trade links in Argentina during Spanish rule. These men encouraged the new Argentinian administration to recruit Irish labourers.

And so, from the early 1820s almost until the end of the century, around 45,000 to 50,000 Irish people travelled to Argentina to start a new life. Not all stayed – some returned home or went on to the USA. But many did stay and prospered. Argentina was doing well economically at the time. It’s position as an independent Catholic country made it an attractive destination, despite language and cultural barriers. Although it probably appealed to the more adventurous type of emigrant.

A Force To Be Reckoned With

Throughout the 1800s a vibrant and successful Irish community established itself in Argentina. Two men in particular were instrumental in making this happen. Fr. Anthony Fahy, a Dominican Prior from Black Abbey in Kilkenny, and Thomas Armstrong, a merchant and family friend of Fahy’s, worked together from 1843 until the early 1870s to copperfasten the Irish position in Argentina.

Fr. Fahy established the Irish Catholic Church in Argentina as a separate entity to the Argentinian Church. This important step ensured the creation of a unique community. Fahy went to great lengths for his congregation and was highly respected by them. He even arranged for female Irish emigrants to travel to Argentina to satisfy a shortage of Irish women in the country. Armstrong remained in the background, dealing with the business community and government to strengthen the Irish position.

Many Irish immigrants trusted Fr. Fahy to conduct their business. He would buy properties in his own name and hold them in trust. This allowed his congregation to avoid being ripped off by unscrupulous traders in a strange land, and to avoid the bother of travelling into the city. As an added advantage, savings could be made on taxes if both parties in a transaction were operating through Fahy.

Eventually, because Fr. Fahy ‘owned’ so much property in Argentina on behalf of his parishioners, he became, on paper, one of the country’s wealthiest people. All this capital was lodged at the bank of Thomas Armstrong. Thus, Armstrong could invest in industries and business opportunities that would benefit the Irish community.

Fahy and Armstrong operated along these lines for almost thirty years, using surplus cash to finance new Irish settlers. The community benefited enormously from the combination of pooled resources and lower taxes. Many poor Irish immigrants even became ranch owners.

End Of An Era

Fr. Fahy died in 1871 and Armstrong followed him four years later. There was no one to fill the void left by these two men. Resources were no longer pooled and new immigrants had nobody to lend them money to establish themselves as landowners.

After Fr. Fahy’s death, opportunities declined for new Irish immigrants. With much of the cheap land already bought up by earlier settlers, and no help from Fr Fahy to establish themselves, they were destined to work as labourers. Added to this, immigrants from other European countries were competing for land and jobs. News began to filter back to Ireland that Argentina was no longer a land of opportunity for the Irish.

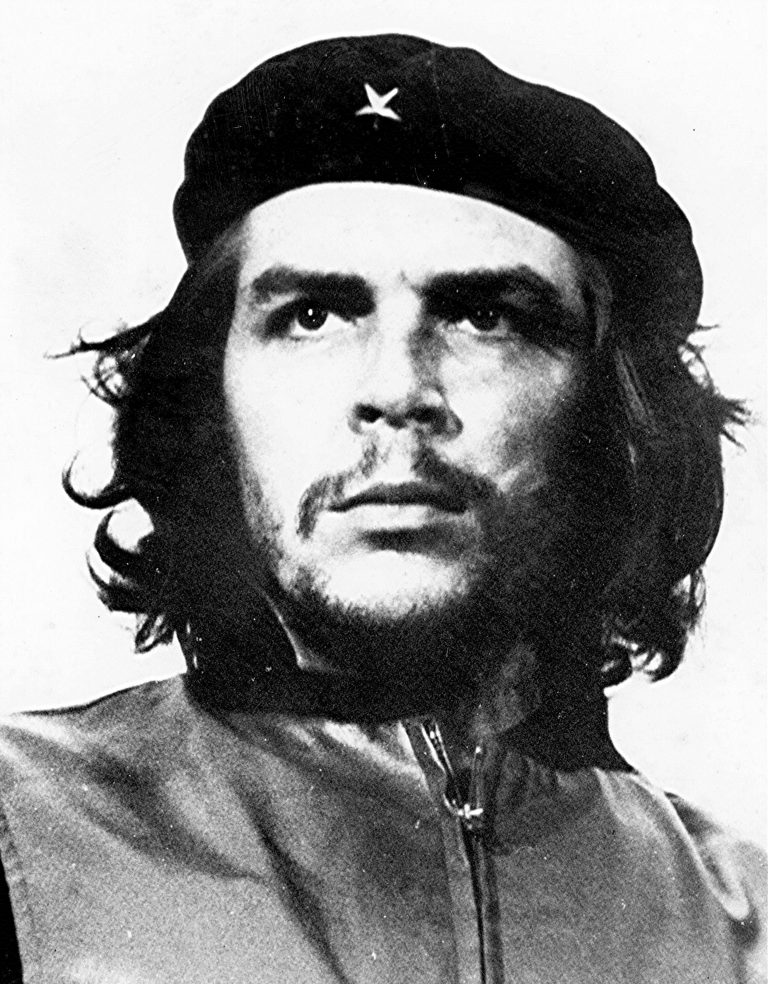

Che Guevara’s great-grandfather was Irish and sailed to Argentina from Co. Galway around the time of the famine.

Che Guevara’s great-grandfather was Irish and sailed to Argentina from Co. Galway around the time of the famine.

The Dresden Affair

But the Argentinian government was still anxious to recruit Irish workers and in 1883 they sent a ship, City of Dresden, to Ireland. It didn’t attract many passengers, however. To avoid returning across the Atlantic with an empty vessel, the recruitment agents picked up destitute people from the streets of Limerick and Cork. They promised to have criminal charges against them dropped if they would emigrate to South America.

There were 1,774 passengers on the City of Dresden. Many died on the journey. When they arrived at Buenos Aires in 1889, nobody wanted to have anything to do with them. Left to fend for themselves, more died due to a lack of help from either the Argentinian administration or the Irish community. Finally, the 700 or so survivors were sent 400 miles away to Bahia Blanca, to establish an Irish community. Needless to say, these poor people struggled to survive. Some went on to the USA and others returned to Ireland.

The treatment of these poor migrants sparked an outcry, both in Ireland and Buenos Aires. The Argentinian government stopped its recruitment efforts in Ireland after this incident, which became known as the Dresden Affair. After 1889, any Irish people arriving in Argentina came on their own steam and tended to be well educated.

Buenos Aires.

Buenos Aires.

The Irish Argentinian Community Today

Nowadays Argentina’s Irish diaspora have adapted to Argentinian life, but the Irish influence is still evident. The Hurling Club of Buenos Aires, established in 1922, is still going strong, although rugby and hockey are the sports played there now. At one time there were numerous hurling teams in Argentina. However, difficulty obtaining the wood to make hurls during World War II meant the game fell into decline and was replaced by hockey.

The Southern Cross, an Irish-Argentine newspaper, is the oldest newspaper in the world dedicated to the Irish diaspora. Published since 1875, it was printed entirely in English until 1977 when it switched to Spanish with some English articles included in each issue. According to the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, by that time Spanish was the first language of most Irish-Argentines.

Today the Irish diaspora in Argentina are more Argentinian than Irish. However, with half a million citizens who can trace their ancestry back to Ireland, strong links to a shared Irish heritage endure. And the stories of the pioneers, explorers and adventurers who travelled there many years ago live on.

Originally published on www.oldmooresalmanac.com