The popular literature genre set in the American Old West frontier had its star writers such as Zane Grey, Johnston McCulley and Louis L'Amour, who achieved great success. But one author wrote about the Wild West entirely in Irish.

Dr. Pádraig Fhia Ó Mathúna takes up the story:

IN 1863, a staggering 94,000 emigrants left Ireland for the United States – a migration driven by rural poverty and political pressure, as well as an increased demand for the manpower to maintain the war effort in the US. Amongst those who began a new life across the Atlantic around this time was Eoin Ua Cathail, a 23-year-old native of Templeglantine, Co. Limerick.

He landed in New York at the end of October that year.

After working briefly for the military, Ua Cathail relocated to the upper Midwest, where he lived a fairly regular existence until his death in 1928. He made his living at various times as a pub owner, barber, farmer, timber surveyor, and for a brief period during the 1870s, as a Chicago police officer.

Yet Ua Cathail transformed himself into a western hero in his extensive writings.

Blending the richness of the Irish language with the eccentricities, casual violence and bravado of the American dime novel, he produced semi-autobiographical tales that reflect a world in which the mythical and the mundane exist seamlessly side by side.

Like many other western literary figures of the time, the deeds described in his writings far outweighed the realities of his lived experience.

An imagined way of life

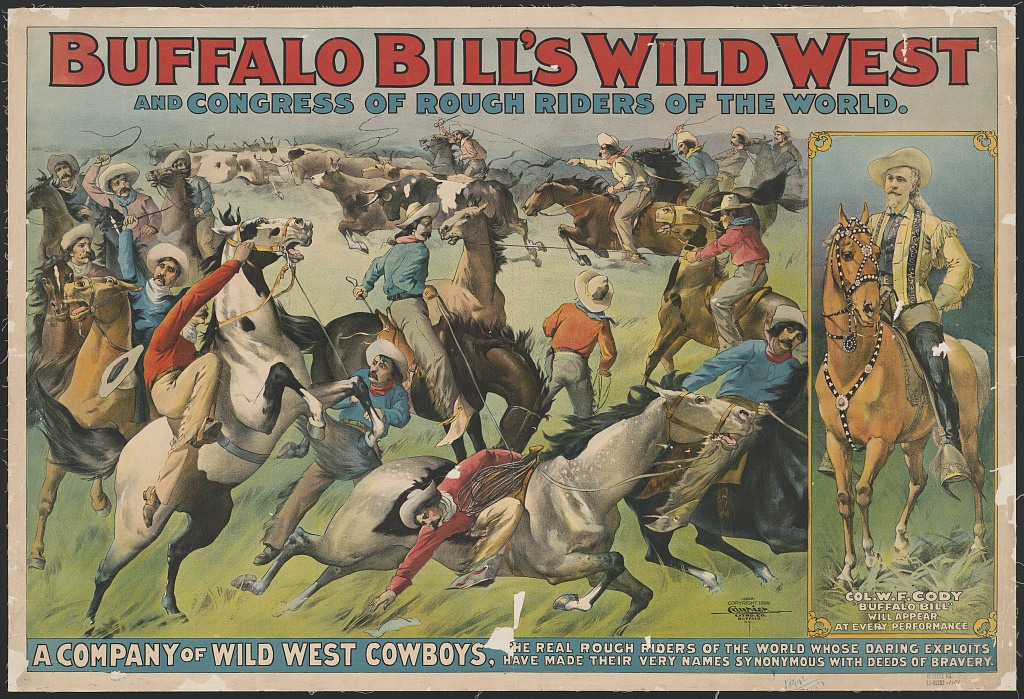

The initial appeal of the western genre in the 1860s was largely built upon exaggerated stories of real, ordinary men and women who found themselves in incredible circumstances. Immortalised in the pages of dime novels, figures like Kit Carson and Buffalo Bill Cody quickly gained widespread acclaim.

Their daring exploits, delivered in formulaic prose set against picturesque yet hostile landscapes, offered a sense of escapism to a mostly urban, working class readership.

Styling himself as more or less an Irish Cody, Ua Cathail delivered first-hand accounts, entirely in Irish, of his purported exploits. In ‘Cuairt air Tecsas’ (Trip to Texas), he recalls a chance meeting with a runaway slave who was being illegally held by his former master — well after both emancipation and the Civil War’s end.

In the same story, he details coming across a woman originally from the same area in Co. Limerick, who had fled to the United States as a child during An Gorta Mór, the Great Famine. She had since married a Mexican man and was operating a pub in Texas.

Within the course of their conversation, she informs Ua Cathail of her family’s plight at the hands of a cruel landlord back in Ireland and their subsequent rise to prosperity in America. Ironically, given her own background of displacement, she expresses her hope to see “the vicious Indians subdued”.

For his part, Ua Cathail recalls his own supposed role in fierce encounters with Native American tribes along the plains, and in one instance details how his mule train and an accompanying cavalry troop orchestrated the slaughter of nearly 450 warriors in a counter-ambush that he deemed to be one of “the most extraordinary” fights ever to take place in North America.

The author’s life

Ua Cathail’s motivation in taking up the pen was at least partially financial, as he confided in a 1924 letter to his niece that if he secured a fair royalty for his stories, he would “be on the pig’s back.”

This belief in a profitable Irish market for frontier literature was well-founded. By the turn of the 20th century, a considerable interest in the genre had developed and remained throughout Ireland.

Following the inaugural tour of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show across the Irish Sea during the spring of 1888, American western entertainment, in the form of similar travelling shows, literature, and later film, gripped the Irish imagination. Accounts of IRA men and women from the revolutionary period are peppered with allusions to Cody and the “Wild West” as they sought to contextualise the violence and danger around them.

Meanwhile, “Cowboys and Indians” is featured amongst the highly popular children’s games in the annals of the Irish Folklore Commission’s Schools’ Collection, collected between 1937–39.

Historian Richard White notes that Eoin Ua Cathail passed himself off as somewhat of an “Irish Robin Hood…saving lives, helping the poor, and punishing the rich.”

Ua Cathail’s Irish language western stories were ultimately never published in Ireland, despite the best efforts of his long-time friend, Douglas Hyde. However, writing from Templeglantine one hundred years ago this spring, Ua Cathail’s daughter Mary, who was only a child when her father emigrated to the United States nearly forty years earlier, offered a glimpse of how one of his unpublished manuscripts had been received locally: “As one Gaelic teacher remarked when he saw your work, ‘I wish’ he said, ‘we had men of his class to build up the youth of the Irish Free State.’”

Reflecting the general climate of uncertainty as civil war loomed, she glumly concluded, “I feel the youth will be weak for some time to come [here] in the Free State.”

Dr. Pádraig Fhia Ó Mathúna - biography

Dr. Pádraig Fhia Ó Mathúna is a researcher on the Fionn Folklore Project at Harvard and a visiting fellow in Irish Studies at Queen’s University Belfast.

Recovering an Irish Voice from the American Frontier: The Prose Writings of Eoin Ua Cathail is available from UNT Press and elsewhere online