IRISH woman Mary Mallon, better known as Typhoid Mary, was the first healthy carrier of typhoid fever identified in the United States.

Mallon, who worked as a cook in New York in the early 20th century, exhibited no symptoms of the disease herself but could pass on the bacterial infection to others.

Today there are around 5,700 cases of typhoid a year in America and it is easily treated with antibiotics, however it was a much bigger threat at the turn of the century – in New York City in 1906, there were 639 deaths from 3,467 cases.

Mallon was first quarantined in 1907 after people she had worked for were struck down with the disease.

She was released three years later only to be returned to isolation in 1915 following a typhoid outbreak that led to two deaths.

She spent the next 23 years in isolation, dying in 1938 from pneumonia.

She was born in Ireland

Mary Mallon was born in Cookstown, Co. Tyrone on September 23, 1869 to Catherine Igo Mallon and John Mallon.

She emigrated to America at the age of 15 and stayed with an aunt and uncle in New York.

It’s possible she was infected with typhoid fever as a child in Ireland and survived, only to become a carrier of the disease without even knowing she had contracted it.

Her profession helped spread the disease

Like many Irish emigrants, Mallon found work as a domestic servant.

She worked as a cook for wealthy families New York, earning a decent living and being renowned for her peach ice-cream.

In the summer of 1906, she was employed by banker Charles Warren at his summer home on Oyster Bay, Long Island.

Three weeks after she started her new job, six of the 11 residents contracted typhoid fever.

Sanitary engineer George Soper was hired to find the cause of the outbreak as the disease was associated with poor people and unsanitary conditions, not wealthy bankers with exclusive addresses.

After initially suspecting a batch of dodgy clams, he turned his attentions to Mallon.

Tracing her employment history, he discovered that since 1900, Mallon had worked at eight different households – seven of which experienced a typhoid outbreak.

Soper's investigation linked 22 cases and one death to Mallon.

The ‘healthy carrier’

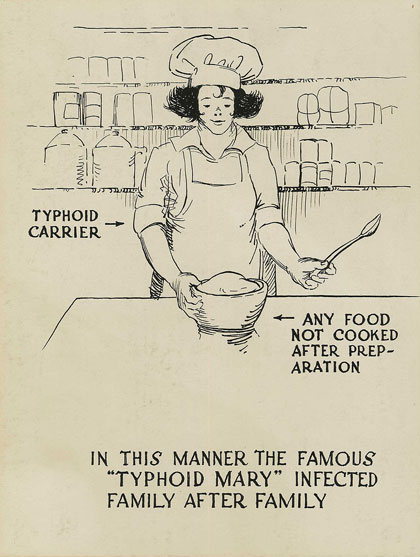

Despite not exhibiting any symptoms, Soper theorised Mallon was an asymptomatic carrier, or ‘healthy carrier’, of the disease.

He believed she spread the bacteria to food by failing to scrub her hands properly – perhaps because, being healthy herself, she never believed she was infected.

However the temperatures required for cooking food would have killed off the bacteria.

The culprit, then, was Mary’s famous peach ice-cream.

Unfortunately, by the time he concluded his investigation, Mallon had once again disappeared as she had done after outbreaks at her previous employers, moving on three weeks after the outbreak at the Warrens.

She had a bit of a temper

When Mallon moved on from each job she failed to give a forwarding address and is also thought to have used different names.

Soper however, determined to obtain samples from Mallon to prove his theory, tracked her down to a penthouse in Park Avenue where there had been an outbreak of typhoid and she was working as a cook.

When he confronted Mallon, she didn’t take kindly to being accused of infecting her employers as she had always been healthy and it undermined her reputation.

According to Fran Capo in Myth and Mysteries of New York, “Mary felt that Soper was desperate to use an immigrant, any immigrant, as a scapegoat to solve the case”.

She allegedly threatened to stab him with a carving fork and Soper left.

He returned with one of the city’s Department of Health doctors, Josephine Baker, but Mallon was again belligerent before fleeing.

When they tracked her down a few hours later, Baker says in her autobiography Fighting For Life that Mallon “came out fighting and swearing, both of which she could do with appalling efficiency and vigor”.

Policemen had to carry her into an ambulance while Baker sat on her to restrain her throughout the journey.

First incarceration

Tests proved that Soper’s theory was correct and despite being in perfect health, Baker wrote that Mallon’s faecal samples were “a living culture of typhoid bacilli”.

She was kept in the custody of the Department of Health for three years from 1907, residing in a bungalow on the grounds of Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island.

Uninhabited before 1885, the island, between the Bronx and Rikers Island, was purchased by the city to build a hospital to house those suffering from contagious diseases.

After working for the elite in a city of millions, Mallon’s only companion in her new quarters was a dog.

An illustration of Mary Mallon in a newspaper article from 1909 (Image: Wikipedia/The New York American)

An illustration of Mary Mallon in a newspaper article from 1909 (Image: Wikipedia/The New York American)Typhoid Mary

A 1908 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association referred to Mallon as Typhoid Mary.

When the press picked up on the story, they also used the name, including in a headline in the New York American newspaper in 1909.

The name was accompanied by an image of a cook tossing skulls into a pan.

Public sympathy

After the press publicised Mallon’s story, the public were sympathetic to her plight.

Like Mallon herself, they believed she was being unfairly persecuted.

She had committed no crime, had not been tried and was being held against her will.

Despite health officials claiming she was a threat, her outward healthy appearance left the public – hitherto unfamiliar with so-called ‘healthy carriers’ – dubious about the authorities’ claims.

It also emerged that Mallon was not the only healthy carrier in the city but was the only one incarcerated.

Capo writes that the public believed Mallon was being targeted because she was Irish and a woman.

Irish attorney George O’Neill filed a lawsuit in the New York Supreme Court on Mallon’s behalf, demanding her freedom on the grounds she was healthy and had committed no crime.

While the suit was unsuccessful, the appointment of a sympathetic health commissioner led to Mallon’s release.

Ernst Lederle freed Mallon in 1910 on the proviso she didn’t work as a cook.

A poster showing how Mallon spread the disease (Image: Wikipedia/Otis Historical Archives – National Museum of Health & Medicine)

A poster showing how Mallon spread the disease (Image: Wikipedia/Otis Historical Archives – National Museum of Health & Medicine)Back to the kitchen

Lederle helped Mallon get a job as a laundress, a role which carried none of the prestige of a cook and paid much less.

Struggling financially and prevented from doing a job she enjoyed and was skilled at, she changed her name to Mary Brown and went back to working in kitchens.

An outbreak at a sanitarium in New Jersey was linked to Mallon, who left shortly after, before getting another job – in a hospital.

The inevitable outbreak at Sloane Maternity Hospital in Manhattan led to 25 cases and two deaths.

Soper was once again the investigator and upon arrival, learnt of a cook the staff had nicknamed ‘Typhoid Mary’ who matched Mallon’s description.

Baker writes that when she went to the hospital, she spotted Mallon.

“Sure enough, there she was earning her living in the hospital kitchen and spreading typhoid germs among mothers and babies and doctors and nurses like a destroying angel.”

Mallon again absconded but when she was tracked down to her home in Queens, she went without a fight.

Second incarceration

There was no sympathy for Mallon this time and after her arrest, she was again quarantined on North Brother Island on March 27, 1915.

She was sentenced to life and, save for supervised trips to the mainland, remained there until her death 23 years later.

By the time of her second incarceration, hundreds more healthy carriers had been identified, however none of them were incarcerated.

Perhaps her belligerence, denial and defiance of the conditions of her release counted against her.

In Casey Carpenter’s Wild Goose Chase, Jess W Thompson writes: “She was persecuted not only for being Irish and a woman, but for being a domestic servant, for not having a family, for having a temper and for disbelieving her status as a carrier.”

Death

Despite denying having infected anyone, Mallon seemed to have accepted her fate.

Something of a model patient, she always returned from her trips to the city on time, and even worked as a technician in the laboratory at Riverside Hospital.

After being left bed-ridden following a major stroke in 1932, she died of pneumonia on November 11, 1938.

After a funeral service with just nine mourners, her remains were cremated and interred at St Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx.

Her headstone reads ‘Jesus Mercy’.