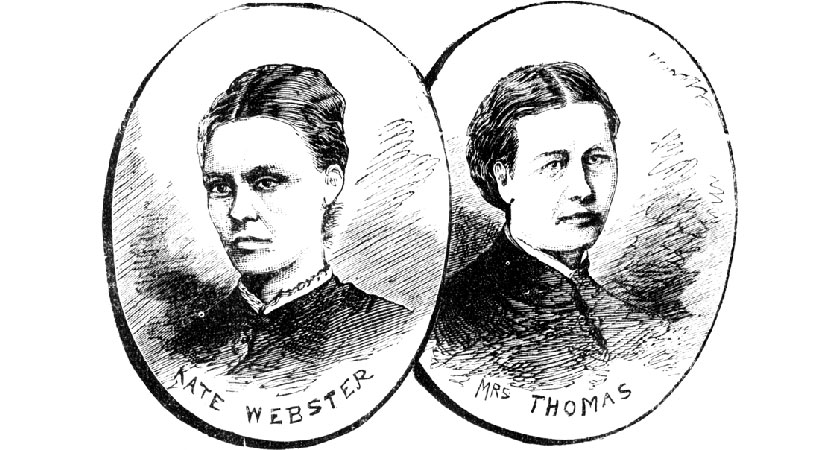

IRISH woman Kate Webster carried out one of the most notorious and savage murders of 19th century England when she killed and dismembered her employer, Julia Martha Thomas.

After fleeing back to Ireland, Webster was arrested on March 29, 1879 and returned to England.

After a trial that gripped the public, she was found guilty of her horrific crime and hanged a few months later.

She started her criminal career early

Born Catherine Lawler in Killanne near Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford in 1849, young Kate gained a reputation for theft from an early age, no doubt causing shame for her poor but respectable parents.

She was imprisoned for larceny in Wexford at the age of 15. After her release, she continued to steal until she raised enough money for a ticket to Liverpool in 1867.

At some point she took the name Webster – one of many aliases – claiming to have married a sea captain of that name and had four children by him. She said the captain and all the children died, but given her propensity for lying, it’s debatable whether they ever existed.

Jail was like a second home

Webster continued her criminal career in Liverpool but in 1868 was sentenced to four years of penal servitude, again for larceny.

After her release in January 1872 she travelled to London and worked as a cleaner and maid, but couldn’t keep out of trouble. She would rent rooms in boarding houses before selling everything of value in the room and absconding.

She spent 18 months in Wandsworth Prison after being convicted of 36 charges of larceny in May 1875. Shortly after her release she was convicted of the same crime and jailed for a further year in February 1877.

The murder was particularly gruesome

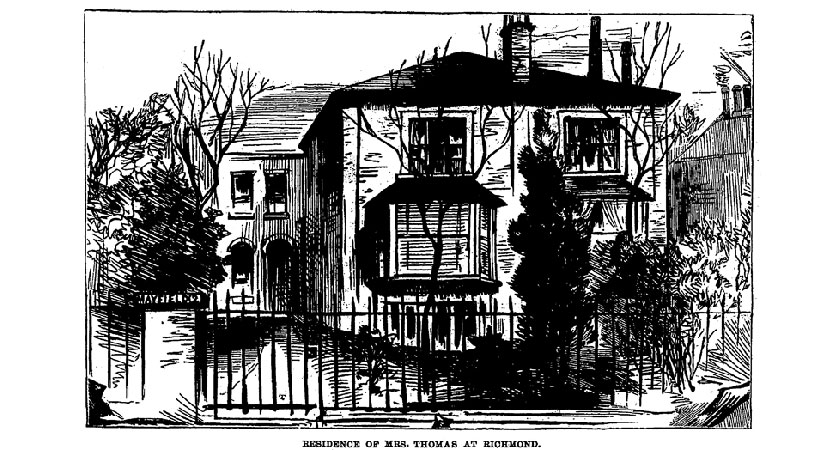

Webster got a job as a domestic servant to twice widowed Julia Martha Thomas in Richmond. She started on January 29, 1879 but Mrs Thomas soon became critical of Webster’s work and gave her notice to finish on February 28. Webster asked for the notice period to be extended until March 2.

On that day the pair quarreled before Mrs Thomas went to church. On her return they again rowed and, according to Webster’s confession, she threw Mrs Thomas down a flight of stairs before choking her. Other reports claim she initially attacked her employer with an axe.

“I chopped the head from the body with the assistance of a razor which I used to cut through the flesh afterwards,” said Webster in her confession. “I also used the meat saw and the carving knife to cut the body up with.

"I prepared the [laundry] copper with water to boil the body to prevent identity; and as soon as I had succeeded in cutting it up I placed it in the copper and boiled it. I opened the stomach with the carving knife, and burned up as much of the parts as I could.”

Webster packed the body pieces – except for the head and one foot – into a box and a bag before throwing them into the Thames. The foot was soon found on a rubbish tip in Twickenham.

It took much longer to recover the head though.

Detective Inspector David Bolton, who examined the case in 2010, said: “A few days after the murder, some boys said that Kate Webster had offered them some food and said ‘here you go lads, I’ve got some good pig’s lard which you can have for free’. The boys ate two bowls of lard, which was unfortunately Mrs Thomas.”

The scene of the crime at 2 Mayfield Cottages, Park Road, Richmond (Image: Penny Illustrated Paper/Wikipedia)

The scene of the crime at 2 Mayfield Cottages, Park Road, Richmond (Image: Penny Illustrated Paper/Wikipedia)She took on her victim’s identity

The box containing some of the remains was found on the banks of the Thames a day later, however it was not identified, as Mrs Thomas hadn’t been reported missing. The bag was never found.

For the next two weeks, Webster lived at her victim’s home, dressing in her clothes and dealing with tradesmen as Mrs Thomas.

Two days after the murder, dressed in one of Mrs Thomas’ dresses, she visited her former neighbours, the Porters, in Hammersmith. She claimed she was now Mrs Thomas, alas widowed, and wanted help selling her home in Richmond that was left to her by an aunt.

The ruse ended on March 18 when deliverymen came to collect furniture Webster had agreed to sell. They told a suspicious neighbour they were working for Mrs Thomas and pointed out Webster. The neighbour alerted the police and Webster fled.

She was fond of a drink

One of the reasons Mrs Thomas sacked Webster was due to her spending more time in the pub than at work. The row on the night of the murder stemmed from Webster returning home late from a visit to her illegitimate five-year-old son, as she had stopped in the pub on the way home.

She reportedly visited a pub while waiting for Mrs Thomas’ remains to boil in the laundry copper, and again treated herself to a drink after pawning her employer’s gold bridgework for six shillings.

After visiting the Porters, she went to the pub with Henry Porter and his son Robert, excusing herself to dispose of the bag with Mrs Thomas’ remains.

Webster also agreed to sell Mrs Thomas’ furniture to a publican named John Church, who she went drinking with several times during the course of their business.

Her trial drew an illustrious audience

Webster fled to Ireland with her son but was arrested on March 29 at her uncle’s farm in Killanne. Crowds jeered her as she was transported to Dublin while her pre-trial magistrate hearing drew “many privileged and curious persons”.

By the time of her trial at the Old Bailey on July 2 – where she was being prosecuted by the Solicitor General, Sir Hardinge Giffard, and defended by prominent London barrister Warner Sleigh – interest had reached fever pitch.

On the fourth day, the future king of Sweden, Crown Prince Gustav, turned up.

She maintained her innocence until the bitter end

Webster pleaded not guilty at her trial, even unsuccessfully implicating Church and Porter. After six days, the jury took just one hour to find her guilty.

Before sentencing, she again pleaded her innocence while also exonerating Church and Porter.

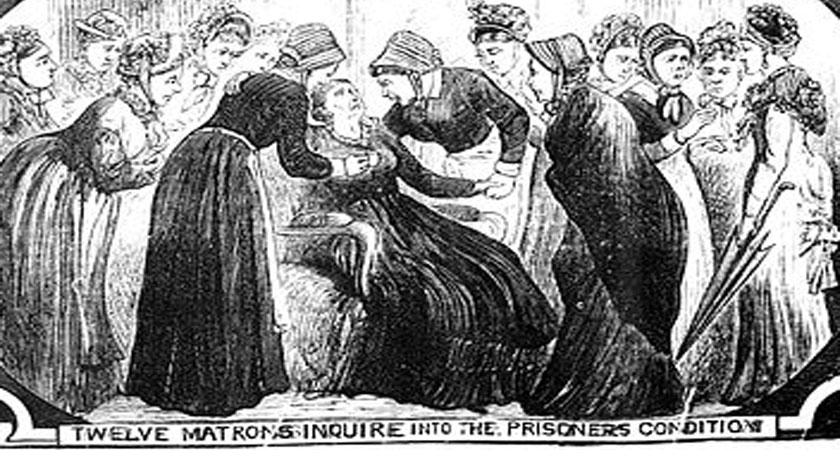

She then claimed she was pregnant in a bid for clemency but a ‘jury of matrons’, employed for just such a scenario, examined her and decided she was lying.

After being sentenced to death, she admitted she had been involved in the murder but implicated a man named Strong, who she claimed was the father of her son and a former criminal accomplice who led her into a life of crime.

However on July 28, the eve of her execution, she finally confessed to her solicitor and a Catholic priest that she had carried out the murder and acted alone.

Her nationality may have counted against her

In the book Murder, by Shani D'Cruze, Sandra L. Walklate and Samantha Pegg, the authors say there was animosity against Irish immigrants who had arrived in England since the Famine as they were associated with “criminality and disorder” – “the stereotype of the unintelligent, drink-prone Irishman was widespread”.

The police’s tendency to target the poorest communities created an over-representation of Irish in prisons, again reinforcing those negative stereotypes.

Thus, the authors argue, “in terms of public and judicial perceptions, it was doubtless easier to accept Webster as both thief and murderer because she was Irish”.

Her hanging made history

Webster was hanged on July 29, 1879 at Wandsworth Prison, only the second person executed there.

Of the 135 people hanged at Wandsworth – including the likes of Lord Haw-Haw and John George Haigh – Webster was the only woman.

As the prison only had 90 graves, they eventually decided to re-use the plots – except for Webster’s. The only woman executed and buried at Wandsworth was allowed to rest alone.

The head turned up in an unlikely place over a century later

While the box containing some of Mrs Thomas' remains was recovered, as well as the severed foot in Twickenham, the head was not found until 131 years later – in David Attenborough’s back garden.

Webster had apparently dumped it under the stables of the Hole in the Wall pub near Mrs Thomas’ home, perhaps refusing to ever reveal its location as without a head, the remains could not be definitively identified as those of Mrs Thomas.

The Planet Earth presenter bought the derelict pub in 2009 with a plan to extend his back garden on to the site. A year later, excavators unearthed a skull.

In 2011, a coroner ruled: “Putting all the circumstantial evidence together there is clear, convincing and compelling evidence that this is Julia Martha Thomas.”