PRIOR to December 3, 1974, Paddy Armstrong was almost unknown to anybody in Britain, outside of a small group of hippies he was sharing a squat with in Kilburn, north London.

His days were usually spent going to the pub, or the bookies. And then, when times got lean, he partook in some small-scale shoplifting to sustain himself.

Armstrong’s evenings, meanwhile, were usually spent in a drug-induced haze. But on an infamous winter night, almost 43 years ago, the then 24-year-old’s life changed forever.

“I was standing in the flat, and the next minute a crowbar came through the door with a cop shouting in my face, ‘don’t move or I will empty these bullets into you’,” recalls the 67-year-old – originally from the Falls Road in West Belfast – from his home in Clontarf, Dublin.

“I could hardly speak, because I was up for three days doing [speed] at the time,” Armstrong explains.

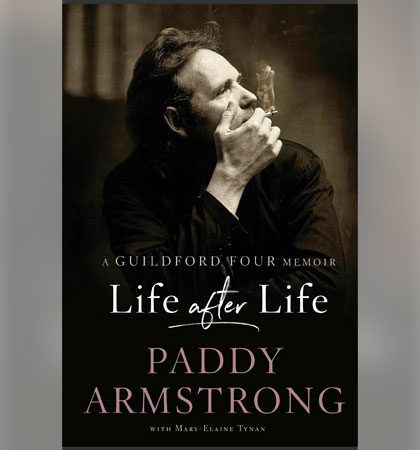

In his recently published book, Life After Life: A Guildford Four Memoir, Armstrong talks about how he was continually beaten by police officers, who also threatened to throw him out of the window where he was being questioned if he didn’t sign a document confessing to the Guildford bombings of October 1974, when five people died and scores of others were injured.

“It was eight days before they even let a solicitor in to visit us,” Armstrong remembers.

And after being on so many drugs, and in a police cell for seven days, you will admit to anything just to get some sleep,” he says.

In October 1975, at the Old Bailey, London, Armstrong, along with Gerry Conlon, Paul Hill and Carole Richardson – who collectively became known as the ‘Guildford Four’ – were charged with the IRA bombings.

Armstrong was also charged with the Woolwich bombings of November 1974, too.

He received a 35-year jail term, at which time judge Mr Justice Donaldson told Armstrong that, had the death penalty not been abolished, he would have sent him to the gallows.

The Guildford Four were eventually released in October 1989, and their innocence was proven. But Armstrong maintains that neither the police, nor anyone from the British legal system, has ever explained to him why he was wrongly convicted of the two bombings.

“I think the police just wanted four people, and we looked like likely suspects,” Armstrong explains.

“Because a year after we were inside in prison, the [IRA] Balcombe Street Gang got arrested, and they told the police, ‘we did Guildford, who you have innocent people in prison for’. We went on an appeal to give evidence. And in the end, the judge just said ‘no you were all in this together’.”

The story of the horrific injustice of the Guildford Four would become internationally recognised after their release, particularly following Jim Sheridan’s 1993 Hollywood film In the Name of The Father, which depicted, in dramatic fashion, the tragic tale that was based on fellow Guildford Four member Gerry Conlon’s memoir Proved Innocent.

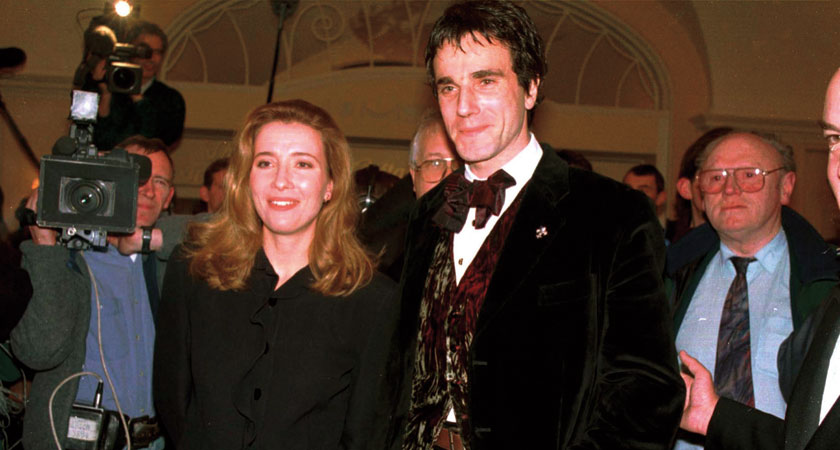

The blockbuster movie starring Daniel Day-Lewis recalled how Conlon’s father Giuseppe died in prison in 1980, while Conlon was serving his sentence.

Emma Thompson and Daniel Day-Lewis at the world premiere of In the Name of the Father in Dublin in 1993 (Image: RollingNews.ie)

Emma Thompson and Daniel Day-Lewis at the world premiere of In the Name of the Father in Dublin in 1993 (Image: RollingNews.ie)It also references the Maguire family – who similarly suffered wrongful accusations – who were closely related to Conlon and became known as the Maguire Seven.

However, what is not talked about as much, when this narrative comes up in the public domain, is the tragic tale of lost romance that occurred between Armstrong and his then girlfriend Carole Richardson, who was just 17 years old when arrested for her so-called involvement in the IRA bombings.

In his latest book, Armstrong reproduces the original love letters between himself and Richardson, and poignantly recalls how they were both supposed to hitchhike around Europe, and eventually marry later that year.

Richardson would go on to suffer several nervous breakdowns in prison before dying in obscurity in 2013, aged just 55, from cancer.

Did the couple ever think of giving it another go, after 15 years in prison? Armstrong becomes quite emotional when asked about this.

“We decided that it probably wouldn’t work between the two of us,” he explained. “But we were still great friends. She was such a most amazing girl. And it broke my heart when I got word that she died in 2013.”

Sometimes I was just so low I would think about suicide

In his memoir, Armstrong reveals, in painstaking detail, just how low he got during several bouts of enforced solitary confinement, locked in his cell for 23 hours a day with just Tolstoy’s War and Peace for company.

During some of the bleaker moments, he recalls that ending his life seemed like ‘the better option than going on’.

“Sometimes, I was just so low I would think about [following through with] suicide,” says Armstrong. “It’s a hard thing to contemplate though – doing yourself in,” he adds.

The day he was released in October 1989, Armstrong had no idea he was about to become a free man.

“I was in the work cell,” he recalls, “and one of the prisoner officers says ‘come on Paddy, I’m taking you down to London for your appeal’.

“And, as me and Gerry Conlon left the prison, along the road it came on the news that we were getting released the next day.

"We were hugging and crying and jumping up and down. One minute you are in prison, the next you are standing on the street in London. It was surreal.”

Following his release, Armstrong went – not without a small dose of irony – to Guildford, where he stayed for some months, with his solicitor Alastair Logan: somebody who worked tirelessly for decades, behind the scenes and without payment, on Armstrong’s behalf in the attempt to prove his client’s innocence.

Today, Logan is godfather to one of Armstrong’s children.

“The reason I went to Guildford was because Alastair got two doctors to treat me,” says Armstrong, “and I think that is what got my head together.

"It was frightening. You are going out to a place you haven’t been in for 15 years. You don’t know what’s changed.”

Following his release, Armstrong was paid £75,000 by the British state as initial compensation.

But having had almost no money at any time in his life to date, Armstrong says he couldn’t handle the pressure of it.

“I was drinking too much,” he says. “Every day, bottles of vodka, and I was gambling, too. And one morning I woke up and a friend I was staying with said, “Paddy, you better get yourself together'. That was it. I cut the spirits out for good.”

“I was drinking too much,” he says. “Every day, bottles of vodka, and I was gambling, too. And one morning I woke up and a friend I was staying with said, “Paddy, you better get yourself together'. That was it. I cut the spirits out for good.”

Today, Armstrong lives a quiet life in the north Dublin suburb of Clontarf and is married to his wife Caroline, with whom he has two children: John and Sophie.

In his darkest moments, during his harsh 15-year prison sentence, did Armstrong ever think he would be able to foresee such a happy ending?

“No, never at all,” he says, and then gives a little chuckle, as if to laugh at the surrealism of it all.

“People say to me, ‘you must be bitter, you must hate a lot of people’ and I say ‘who do I hate? I certainly don’t hate English people’.”